-

The power and the story

If only paintings could talk, who knows what they would disclose?

Well, during a visit to the National Museum of Fine Arts, in Valletta, Principal Curator, Sandro Debono, revealed to me that though these works of art might appear to be silent, in reality they do possess the ability to communicate with us, and sometimes even more than we could possibly expect.

Being no art specialist, had I strolled around this museum by myself, I would have lost much of the inaudible discourse which emanated from these paintings. However, through Sandro’s guidance, I was enabled to listen to the soundless utterings that were emitted by the painters’ skilled brush strokes. The truth was is in the detail and in the knowledge of the social history pertaining to the period being illustrated.

“These elements will be featuring in the new concept of MUŻA, as this museum shall become known once it is relocated to its new site in Valletta. Indeed, the primary mission of this museum will be that of communicating and reaching out to a broader and more varied audience base. As I will show you today, MUŻA visitors will not only be invited to appreciate the artists’ works and their artistic merits but also to discover the stories behind each illustration,” explained Sandro as he introduced me to some of the artworks of his museum.

We decided to focus on the portraits of some of the French Grand Masters of the Order of St John in Malta. At first glance, all the paintings looked like standard images to me but then Sandro started to point out the deliberate clues which openly manifested the purposeful messages and meanings that were originally intended to reach the viewers. Though nowadays, many of these connotations have to be identified for the public, undoubtedly the people at the time would have recognized clearly what was being proclaimed…

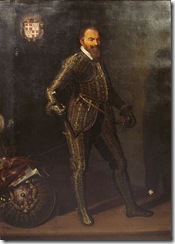

The first portrait flaunted the exuberant richness of Grand Master Fra’ Alof de Wignacourt (1601 – 1622) as he is pictured standing proudly in his new parade armour which was fully embellished with gold. It is not difficult to understand the awe that such armour would have created during his time. Shining brightly under the strong sun of a beautiful morning, Alof de Wignacourt would have looked like an ethereal vision; a magnificent prince of godly status. Even today, this armour is regarded as a spectacular ‘show-piece’ in the collection of the Palace Armoury.

In fact, this painting was intended to convey a sense of utter power in order to bolster even more this influential man’s reputation. He had been the one who paid from his own pockets for the construction of St Thomas tower in Marsascala, St Lucian tower in Marsaxlokk, Wignacourt tower in St Paul’s Bay, and the Wignacourt aqueduct in Attard. He had fought many battles, including those of the Great Siege of Malta in 1565 and in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 wherein the Christians emerged victorious. With the baton held firmly in his right hand, Alof de Wignacourt reminds the people that he is in command, whereas his thoughtful and firm gaze, sharply captured by the still unknown artist, gives out the feeling that he is already pondering another mission and that more is yet to come.

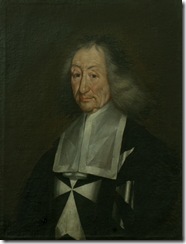

Interestingly, although the next portrait which I visited reproduced the image of another Grand Master who happened to be the nephew of Grand Master Fra’ Alof de Wignacourt, the contrasting reflections between the two could not be any more different. For the portrait of Grand Master Fra’ Adrien de Wignacourt (1690 – 1697), also rendered by an unknown artist, relates the presence of a humble-looking old man with a wise look which seems to recall all the experiences that he had lived through. His grey hair is combed back to reveal a shriveled face which clearly betrays the age of this man. There are no impressive decorations on his black austere clothes except for the eight pointed white cross of the Order.

Fra’ Adrien de Wignacourt was the one who had established a relief fund for widows and orphans in Malta, after their husbands and fathers had lost their lives during wars against the Turks. He had also been the considerate Grand master who had provided the Maltese people with abundant supplies after the islands were hit by an earthquake in 1693. And in this sensible portrait he seems to have simply wanted the viewers to meet the real man in him.

This perception changes completely during the rule of Grand Master Fra’ Emmanuel Pinto de Fonseca (1741 – 1773). In fact, his portrait shows a defiant and proud man with a bold look in his eyes which manifest a very direct statement – I am the one in power! He wears an elegant wig according to the highest fashion of the time and he elaborates the standard black clothes of the Order, by wearing fine lace and ermine decorations that were usually worn by kings.

He lived at a time when the sovereignty of the Order was being challenged by the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, but he was adamant that nobody had the right to interfere with their regulations. To confirm his determination, he introduced the symbol of the closed crown which symbolized supremacy and in this portrait he is seen holding firmly onto it. A curtain of flowing red silk painted in the background augments the sense of power, and though the Grand Master’s left hand is open and welcoming, no one could be fooled by this gesture. For this painting, elegantly finished by renowned artist, Antoine de Favray (1706 – 1798) has no other message to convey but Pinto`s great personal ambitions for authority, pageantry, pomp and splendour, which attitude eventually left the Order in great financial troubles.

This short tour ended in front of the huge painting which presents a full length portrait of Grand Master Fra’ Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc (1775 – 1797). Again, though only a few years have passed from Pinto’s rule, a considerable difference can be observed between the portrayals of the two Grand Masters. Indeed, Pinto’s ermine decorations are gone and though De Rohan is depicted by artist De Favray in an authoritative stance, his clothes have resumed the standard somber black uniform with the white eight-pointed cross of the Order. The Grand Master is also wearing a different kind of wig, indicating that the fashion had changed. Yet this is only one little detail in a comprehensive painting which is full of conspicuous hints that are acutely marking a considerable transition that is taking place within the Order.

In fact, in this portrait, the Grand Master is not standing alone like the previous Grand Masters had done, and though his left hand rests on an elevated throne, he is stepping on the same ground as his pages. Curiously, though one of the pages is humbly receiving De Rohan’s hat, another three pages standing in the background, seem to be completely absorbed in a discussion, totally ignoring the presence of their leader. Even the crown has been moved at the back of this illustration, appearing as if it is only there as an incidental decoration. A red silk curtain is once again present, but this time, it is withdrawn further up in order to reveal the crowd standing outside and cheering at the election of the new Grand Master.

Surely, this painting transmits a feeling of a more sympathetic Grand Master who is trying to get closer to the people. However, in reality De Rohan had no choice than to represent himself in this manner. One should remember that during this era, at the end of the 18th century, people were no longer content with the status quo, and in France there was a period of radical social and political upheaval. It would only take a few years more in order to reach the climax of the French revolution and some of the Grand Master’s relatives had already been decapitated and their lands confiscated. Indeed, De Rohan reigned up to 1797, only a year before his successor, Grand Master Fra’ Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim, together with all the members of his Order, had to leave our islands immediately once Napoleon Bonaparte disembarked in Malta with his French fleet.

(This feature was published in MAN MATTERS Suppliment in the TIMES OF MALTA dated 14th June 2014)

Category: Torca - Perspettivi | Tags:

![[#Beginning of Shooting Data Section]

Nikon D2Xs

2009/03/18 11:42:20

RAW (12-bit)

Image Size: Large (4288 x 2848)

Color

Lens: 24-120 mm F/3.5-5.6 D

Focal Length: 38 mm

Exposure Mode: Manual

Metering Mode: Multi-Pattern

8 s - F/16

Exposure Comp.: 0 EV

Sensitivity: ISO 100

Optimize Image:

White Balance: Auto

Focus Mode: AF-S

VR Control: OFF

Long Exposure NR: ON

High ISO NR: Off

Color Mode: Mode I (Adobe RGB)

Tone Comp.: Auto

Hue Adjustment: 0°

Saturation: Normal

Sharpening: Normal

Image Authentication: OFF

Image Comment:

[#End of Shooting Data Section]

[#Beginning of Shooting Data Section]

Nikon D2Xs

2009/03/18 11:42:20

RAW (12-bit)

Image Size: Large (4288 x 2848)

Color

Lens: 24-120 mm F/3.5-5.6 D

Focal Length: 38 mm

Exposure Mode: Manual

Metering Mode: Multi-Pattern

8 s - F/16

Exposure Comp.: 0 EV

Sensitivity: ISO 100

Optimize Image:

White Balance: Auto

Focus Mode: AF-S

VR Control: OFF

Long Exposure NR: ON

High ISO NR: Off

Color Mode: Mode I (Adobe RGB)

Tone Comp.: Auto

Hue Adjustment: 0°

Saturation: Normal

Sharpening: Normal

Image Authentication: OFF

Image Comment:

[#End of Shooting Data Section]](http://fionavella.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Grand-Master-Fra-Emmanuel-Pinto-de-Fonseca-Photo-Credit-Heritage-Malta_thumb.jpg)

![[#Beginning of Shooting Data Section]

Nikon D2Xs

2009/03/18 09:56:34.7

RAW (12-bit)

Image Size: Large (4288 x 2848)

Color

Lens: 24-120 mm F/3.5-5.6 D

Focal Length: 38 mm

Exposure Mode: Manual

Metering Mode: Multi-Pattern

30 s - F/6.3

Exposure Comp.: 0 EV

Sensitivity: ISO 100

Optimize Image:

White Balance: Auto

Focus Mode: AF-S

VR Control: OFF

Long Exposure NR: ON

High ISO NR: Off

Color Mode: Mode I (Adobe RGB)

Tone Comp.: Auto

Hue Adjustment: 0°

Saturation: Normal

Sharpening: Normal

Image Authentication: OFF

Image Comment:

[#End of Shooting Data Section]

[#Beginning of Shooting Data Section]

Nikon D2Xs

2009/03/18 09:56:34.7

RAW (12-bit)

Image Size: Large (4288 x 2848)

Color

Lens: 24-120 mm F/3.5-5.6 D

Focal Length: 38 mm

Exposure Mode: Manual

Metering Mode: Multi-Pattern

30 s - F/6.3

Exposure Comp.: 0 EV

Sensitivity: ISO 100

Optimize Image:

White Balance: Auto

Focus Mode: AF-S

VR Control: OFF

Long Exposure NR: ON

High ISO NR: Off

Color Mode: Mode I (Adobe RGB)

Tone Comp.: Auto

Hue Adjustment: 0°

Saturation: Normal

Sharpening: Normal

Image Authentication: OFF

Image Comment:

[#End of Shooting Data Section]](http://fionavella.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Grand-Master-Fra-Emmanuel-de-Rohan-Polduc-Photo-Credit-Heritage-Malta_thumb.jpg)