Archive for the ‘Malta Independent on Sunday – First magazine’ Category

-

LOOK OUT, BEHIND YOU

GREZZJU VELLA accompanied me up to the roof of St Gregory’s Church, and pointed out the area where the opening to his macabre revelation had been discovered. Boldly he even ventured into the three passageways but he refused to approach the skeletons lying before us in solemn silence.

Since 1969, a series of secret passages accidentally discovered by a 16-year-old Grezzju within the historic church of St Gregory which was rebuilt in the 15th Century, have posed an unsolved riddle. Inside were a heap of skeletons – a shocking discovery that left a deep and troubling impression on the young man. After reporting the find, he decided to avoid speaking about the incident, until now, at age 58, he felt ready to open up to me about it.

Among the skeletons were some medieval coins, a Byzantine cross, a metal net which historians identified as of a type that used to be worn under a suit of armour, and a shoe-sole. No one knows why these remains were in these tunnels or who the skeletons belonged to. Initially it was believed that they were the unfortunate victims of a Turkish or pirate attack, of the type that were quite frequent in the days of when and after the church was built. However in 1978, nine years after this discovery, these remains have undergone paleopathological studies, producing the first report on medieval bones found in Malta (1). Both the evidence of soil within some bones and the wide discrepancy in the total number of bones pertaining to various parts of the body indicated that probably these were exhumed from some sort of cemetery. Most of the skeletons were very well preserved, possibly because they were confined in a completely covered and well ventilated passage. Among the bones, 19 male skulls and 24 female skulls were discovered, the youngest belonging to a child of about 8 years. It was not possible to arrive at a conclusion about the cause of death of these individuals but the appearance of the bones suggested that these people had died within a short time from each other. Eventually the experts who conducted this analysis, Seshadri Ramaswamy and Joseph Leslie Pace, came to the conclusion that most likely, one of the passages was used as an ossuary. Tentatively they also proposed the idea that these bones could have been moved to this location when some graves were cleared in order to make space for the original extension of the church (2).

Among the skeletons were some medieval coins, a Byzantine cross, a metal net which historians identified as of a type that used to be worn under a suit of armour, and a shoe-sole. No one knows why these remains were in these tunnels or who the skeletons belonged to. Initially it was believed that they were the unfortunate victims of a Turkish or pirate attack, of the type that were quite frequent in the days of when and after the church was built. However in 1978, nine years after this discovery, these remains have undergone paleopathological studies, producing the first report on medieval bones found in Malta (1). Both the evidence of soil within some bones and the wide discrepancy in the total number of bones pertaining to various parts of the body indicated that probably these were exhumed from some sort of cemetery. Most of the skeletons were very well preserved, possibly because they were confined in a completely covered and well ventilated passage. Among the bones, 19 male skulls and 24 female skulls were discovered, the youngest belonging to a child of about 8 years. It was not possible to arrive at a conclusion about the cause of death of these individuals but the appearance of the bones suggested that these people had died within a short time from each other. Eventually the experts who conducted this analysis, Seshadri Ramaswamy and Joseph Leslie Pace, came to the conclusion that most likely, one of the passages was used as an ossuary. Tentatively they also proposed the idea that these bones could have been moved to this location when some graves were cleared in order to make space for the original extension of the church (2).Within the passageways, Grezzju took me back to that fateful day in 1969.

“I had never heard any rumours about the existence of secret passages built round the dome of St Gregory’s church in Żejtun. If I had known, I would certainly have kept away from the roof of the church upon which one day I was thoughtlessly scratching away – a scratching that revealed the sealed opening.

“I had never heard any rumours about the existence of secret passages built round the dome of St Gregory’s church in Żejtun. If I had known, I would certainly have kept away from the roof of the church upon which one day I was thoughtlessly scratching away – a scratching that revealed the sealed opening.I was helping with the maintenance of the wooden apertures of the old church, together with my uncle Carmelo Spiteri and a fellow worker Ċikku Zammit, when Dun Ġwann Palmier asked us to take a look at the roof as it was leaking rain-water. Up we went, walking around the ancient dome which is thought to be one of the oldest domes in Malta. The views up there are beautiful… at least if you avoid looking at the nearby cemetry crowded with ghostly white-marbled tombs. I don’t know why but I always had an instinctive fear of the dead and death itself, a strong gut-feeling which I could not suppress, not even today.

I was probably just trying to kill time as I sat down and scraped off at a narrow fracture on the roof whilst the others were inspecting the rest of the area in order to identify the parts where grouting was needed. To my surprise, the more I hacked at the crack, the more it widened, till at one point I decided to throw a pebble inside to see whether I could hear it fall into the church below. However oddly enough, when I threw it in, I heard it falling nearby and I realized immediately that there could be some sort of structure within the dome itself. I called the others who at first did not take much notice of what I was doing, but when it became evident that there was an ashlar block, my uncle urged me to carve it out. Curiously I slashed off the remaining sealant and on taking the block away, we found that it had been acting as a perfect wedge to lock the opening to a chamber.

I was probably just trying to kill time as I sat down and scraped off at a narrow fracture on the roof whilst the others were inspecting the rest of the area in order to identify the parts where grouting was needed. To my surprise, the more I hacked at the crack, the more it widened, till at one point I decided to throw a pebble inside to see whether I could hear it fall into the church below. However oddly enough, when I threw it in, I heard it falling nearby and I realized immediately that there could be some sort of structure within the dome itself. I called the others who at first did not take much notice of what I was doing, but when it became evident that there was an ashlar block, my uncle urged me to carve it out. Curiously I slashed off the remaining sealant and on taking the block away, we found that it had been acting as a perfect wedge to lock the opening to a chamber.We decided to stop and called for Dun Gwann to come and have a look. The discovery left him puzzled because although he had been responsible for the upkeep of the church for some time, he had never known about this chamber, although he had heard folk tales of hidden passages located in the vicinity of the church. Soon after we were also joined by Ġanmarì Debono, the sacristan of the church, who also had no idea where this opening could lead to. Since I was the youngest and the leaner one, it was decided that I should be lowered down with a rope so that I could see what was inside.

They tied a rope around my waist and gave me a box of matches to find my way through in the darkness. As soon as I touched the floor I lit the first match and in the few seconds of light that it gave me, I managed to see that I was in some sort of passage. With the aid of the fleeting weak light of one match after another, I walked a distance of about 30 feet, but there was much more space in front of me. I hesitated and nervously turned back, alerting the others that the area covered much more than we had originally thought.

They tied a rope around my waist and gave me a box of matches to find my way through in the darkness. As soon as I touched the floor I lit the first match and in the few seconds of light that it gave me, I managed to see that I was in some sort of passage. With the aid of the fleeting weak light of one match after another, I walked a distance of about 30 feet, but there was much more space in front of me. I hesitated and nervously turned back, alerting the others that the area covered much more than we had originally thought.It was then that Dun Gwann had a premonition that I had found the enigmatic passages that people used to narrate stories about. Strangely enough, some years earlier some people had tried to unveil the truth about these tales by trying to open through a side of the dome, but they had not found anything. Dun Gwann told me that the passage would probably lead all the way round the dome, and he calmly encouraged me to go back and find out. He assured me that I would be safe as I was securely tied to the rope, so I plucked up some courage and went back in.

The remaining matches accompanied me along the passage where it abruptly seemed to end, when I suddenly found myself treading on a mass of objects scattered beneath my feet. I felt around with my hands and my fingers came to something resting on the wall in front of me. The darkness was complete while I fumbled at the object to try and understand what it was. My fingers ran over two gaping holes… and then I felt what seemed to be a row of teeth! To my utter shock I recognized that I was holding a skull!

I will never forget the sound of crunching bones as, having let go of the skull with a scream, I turned on my heels and raced back to the faint safety of the light where I had come from. Distraught and agitated I told the others what I had found and left the rest to them.

I will never forget the sound of crunching bones as, having let go of the skull with a scream, I turned on my heels and raced back to the faint safety of the light where I had come from. Distraught and agitated I told the others what I had found and left the rest to them.The incident devastated me at the time, as the fear of anything associated with death that had always lurked within me came out with a vengeance and engulfed me in a state of shock. An ugly rash broke out over my skin and it took me months to calm down completely. I remember my mum Michelina being enraged at my uncle who had allowed me to go down there even though he was aware of my phobia.

From then on I rarely even mentioned this incident to anyone. And even though news of the discovery of the secret passages was quite a sensation back in 1969, I did not reveal to any of my school friends that I had played such an important role in their exposure, I don’t know why. Maybe I simply wanted to be left alone with the hope that one day I would forget this terrible experience. Yet I never really succeeded in doing this, and even though my parents and my brother are buried in the church’s cemetry, for many years I could not ever convince myself to return there. Though I live in the vicinity of the church itself, I’ve tried my best to always avoid going near it. It makes me feel uneasy.

This is the first time that I have been in these passages since that fateful day 42 years ago… and this is the first time I’ve told the story in its entirety to someone from the media. But today I was determined to settle this long-standing debt that has ruled my life for so long and come to terms with the experience. It’s time to move on.”

This is the first time that I have been in these passages since that fateful day 42 years ago… and this is the first time I’ve told the story in its entirety to someone from the media. But today I was determined to settle this long-standing debt that has ruled my life for so long and come to terms with the experience. It’s time to move on.”And with that, we moved out of the haunting passages. Each year, after Easter, a votive traditional procession culminates at this magnificent church which is endowed with distinguished culture, history and architecture. But few of the faithful who congregate for the procession probably know of the enigma waiting to be resolved, save for the few who remember hearing about the discovery all those years ago. A recently formed NGO bearing the name of Wirt iż-Żejtun has vowed to investigate further this unsolved mystery. Maybe finally the time will come for these souls to tell the story and then forever rest in peace.

References

(1) Ramaswamy S & Pace J. L, 1979. The medieval skeletal remains from St. Gregory’s Church at Żejtun (Malta) – Part 1 Paleopathological Studies in Archivio Italiano Di Anatomia E Di Embriologia, Vol. LXXXIV – Fasc. 1.

(2) Ramaswamy S & Pace J. L, 1980. The medieval skeletal remains from St. Gregory’s Church at Żejtun (Malta) – Part 2 Anthropological Studies in Archivio Italiano Di Anatomia E Di Embriologia, Vol. LXXXV – Fasc. 1.

(Note: An edited version of this article was published on FIRST magazine - Issue: April 2011)

-

THE NATIVITY IN MINIATURE

When the last month of the year steals its way into our hearts, we find ourselves in a world of light, colours, dreams, hopes and Christmas… and nothing symbolises the

Christmas spirit better than the nativity scene captured in a traditional crib. Fiona Vella went in search of two remarkable examples of this long-standing Maltese tradition.

Christmas spirit better than the nativity scene captured in a traditional crib. Fiona Vella went in search of two remarkable examples of this long-standing Maltese tradition.As December comes round, out come the boxes loaded with colourful accessories and delights which were stored away the previous year: a disassembled Christmas tree, some intricate ornaments and a few old cherished cards.

Yet nothing compares to the allure of a precious crib with its little figurines and the statuette of baby Jesus which needs to be warmed up with Ġulbiena, at least in a country with a strong Christian

tradition like Malta. The annual ritual of setting up the crib is fascinating, but what is this enigmatic fascination which draws us each year to recreate this nativity scene? To unearth this riddle I decided to go back to our roots, seeking out two beautiful antique treasures which lie within our intriguing island.

tradition like Malta. The annual ritual of setting up the crib is fascinating, but what is this enigmatic fascination which draws us each year to recreate this nativity scene? To unearth this riddle I decided to go back to our roots, seeking out two beautiful antique treasures which lie within our intriguing island.MDINA

The first gem is situated deep in the heart of the medieval town of Mdina, shielded in the core of St Peter’s Monastery, the domicile of the Benedictine Cloistered Nuns.

With the aid of Joseph Flask, a diligent writer about the life and history of the Benedictine Monastic Order, I was allowed to meet the Rev. Mother Abbess Sr. Maria Adeodata Testaferrata de Noto OSB who received me warmly and invited me to view the oldest known static crib in Malta.

The monastery itself is a magnificent historic and architectural site, dating back to the 15th century. Nevertheless the experience of stepping inside a location which is customarily prohibited to

outsiders’ eyes took that sense of magnificence one step further.

outsiders’ eyes took that sense of magnificence one step further.Up the stairs and along the innermost corridors, lying dormant behind a wide glass case and heavy curtains was my ‘prize’, and I was overwhelmed with emotion as I beheld this rarely seen fine example of one of the highest Maltese traditions.

No one knows who was its original creator or when it was built, but probably the crib’s first restoration took place in 1826, as the earliest painted signature G.B.G

indicates. A similar unspecified restorer enlarged the crib in 1846 and left a simple mark of G.G. A final revamp dates back to 1977, this time clearly signed by Giuseppe Sammut who painted and added the crib’s scenery.

indicates. A similar unspecified restorer enlarged the crib in 1846 and left a simple mark of G.G. A final revamp dates back to 1977, this time clearly signed by Giuseppe Sammut who painted and added the crib’s scenery.Incredibly, while we were exploring the crib, we chanced upon another signature which Joseph had never noticed before – a coarse reddish scribbling bearing the initials G.G and a not so clear G.I. Evidently the crib seems to hold even more challenges and clues for devotees to decipher.

The crib is embedded with personal memories of several people. In fact, a closer glimpse at its figurines lying around the

unrefined landscape made of glued old sacks and newspapers, reveals that oddly most of the figures do not match each other, either in style, age or even size! This effect was initiated by the nuns themselves when they resolved to bestow the original crib’s population with every relative statuette that came in their possession! Amusingly, more intense exploration discloses even extraneous insertions; such as the Greek classic statuette and an irrelevant building situated at the back. Peculiar as it might seem, this reality exudes a tender feeling as one realizes that the crib actually encompasses the love and memories of each nun that lived with it.

unrefined landscape made of glued old sacks and newspapers, reveals that oddly most of the figures do not match each other, either in style, age or even size! This effect was initiated by the nuns themselves when they resolved to bestow the original crib’s population with every relative statuette that came in their possession! Amusingly, more intense exploration discloses even extraneous insertions; such as the Greek classic statuette and an irrelevant building situated at the back. Peculiar as it might seem, this reality exudes a tender feeling as one realizes that the crib actually encompasses the love and memories of each nun that lived with it.The crib is in fact of somewhat crucial help to the cloistered nuns, helping them to evoke the

meaning behind the holy birth; a tangible item in a life withdrawn from the usual worldly pleasures, which constantly reminds them of the sweet joy of Christmas. Indeed, this very crib inspired the renowned short writings of the Blessed Maria Adeodata Pisani OSB who lived in the monastery for several years. And to this day, the crib continues to instigate the spirits of the other nuns when on Christmas Eve they celebrate a traditional procession which ends up in front of it.

meaning behind the holy birth; a tangible item in a life withdrawn from the usual worldly pleasures, which constantly reminds them of the sweet joy of Christmas. Indeed, this very crib inspired the renowned short writings of the Blessed Maria Adeodata Pisani OSB who lived in the monastery for several years. And to this day, the crib continues to instigate the spirits of the other nuns when on Christmas Eve they celebrate a traditional procession which ends up in front of it.ŻEJTUN

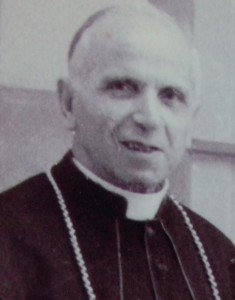

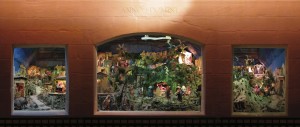

The other route to discovery led me to the quaint village of Żejtun, again to another convent but this time to see the oldest, large, Maltese mechanical crib, which dates back to 1945, a period wherein

our island lay ravaged from the destruction of World War II. It was this devastation that inspired Mons. Emmanuel Galea to create a unique religious symbol as he saw that people desperately needed to rekindle their faith and hope of a better life.

our island lay ravaged from the destruction of World War II. It was this devastation that inspired Mons. Emmanuel Galea to create a unique religious symbol as he saw that people desperately needed to rekindle their faith and hope of a better life.Together with his nephew Pawlu Pavia he devised a plan to build a large mechanical crib which could be motor-driven.

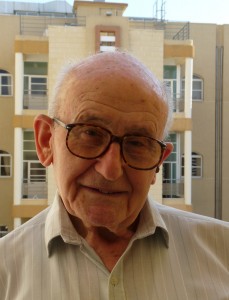

I found Pawlu, now 86, residing in St Vincent De Paule’s residence. Despite his old age, he reconstructed the whole story with sharp clarity and also with a touch of melancholy.

He remembers how some workers were brought in to build a platform made from random pieces of broken doors and windows. Moreover, three openings were cut in one of the room’s wall as the crib

had to represent three sections: what happened before the birth of Jesus Christ, the actual birth itself and what occurred thereafter.

had to represent three sections: what happened before the birth of Jesus Christ, the actual birth itself and what occurred thereafter.The fabrication of papier machè and the layout of the crib he made with the bishop, while he alone was responsible for building the crib’s figurines from wood and iron wire. However the hardest task

was to find some ingenious way of motorizing the figurines’ movements and to actually interelate them at a time when resources were very few. Another difficulty was to surpass the dilemma of an unstable electric current. Incredibly he did all this by means of one single motor which he succeeded to find in a remote shop. Even more incredible is that after 65 years, the crib still functions with this same system!

was to find some ingenious way of motorizing the figurines’ movements and to actually interelate them at a time when resources were very few. Another difficulty was to surpass the dilemma of an unstable electric current. Incredibly he did all this by means of one single motor which he succeeded to find in a remote shop. Even more incredible is that after 65 years, the crib still functions with this same system!This journey also led me to Sister Pawlina Gauci, now 78, who, together with the late Sr. Angela, had the responsibility of dressing the figures. Her three years

missionary work in Persia (now Iran) aided her with good knowledge of the type of material to be used and one by one the figures were clothed with several samples of fabric which a number of shops had contributed.

missionary work in Persia (now Iran) aided her with good knowledge of the type of material to be used and one by one the figures were clothed with several samples of fabric which a number of shops had contributed.Both Pawlu and Sr. Pawlina recall the commotion that this crib raised when it was opened to the public for the first time during Christmas of 1947. Visitors came from all over Malta and there was such a big crowd that the police had to intervene to keep control of the situation!

Now that Pawlu is retired, the crib passed into the care of his nephew Joseph Pavia,

whose great dedication to it is no lesser than his uncle’s. In fact during the last years Joseph renovated the visitors’ room and included a very interesting documentary which recounts the whole story of this crib in five different languages.

whose great dedication to it is no lesser than his uncle’s. In fact during the last years Joseph renovated the visitors’ room and included a very interesting documentary which recounts the whole story of this crib in five different languages.Remarkably, even this crib seems to bear the destiny to be associated with holiness as currently there is the process of the cause for canonization of its instigator, Mons. Emmanuel Galea.

As I left the crib, I pondered about the dedication and devotion behind their creation. The endeavour, the ritual, the almost childish happiness to share a crib with others… all lead to an ancient dream

which St Francis of Assisi had foreseen a long time ago in the village of Greccio. For through its modesty, a crib reminds us that the spirit of Christmas is simple and that it is meant to reach out to our hearts and souls and bathe them in the joy of the birth of Jesus.

which St Francis of Assisi had foreseen a long time ago in the village of Greccio. For through its modesty, a crib reminds us that the spirit of Christmas is simple and that it is meant to reach out to our hearts and souls and bathe them in the joy of the birth of Jesus.(This article was published in FIRST magazine, Issue December 2010. FIRST magazine is delivered with The Malta Independent on Sunday)

Travelogue

Archives

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jan | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

Recent Posts

- A MATTER OF FATE

- MALTA’S PREHISTORIC TREASURES

- THE MAGIC IS IN THE DETAIL

- THE SELLING GAME

- NEVER FORGOTTEN

- Ġrajjiet mhux mitmuma – 35 sena mit-Traġedja tal-Patrol Boat C23

- AN UNEXPECTED VISIT

- THE SISTERS OF THE CRIB

Comments

- Pauline Harkins on Novella – Li kieku stajt!

- admin on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Albert on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Martin Ratcliffe on Love in the time of war

- admin on 24 SENA ILU: IT-TRAĠEDJA TAL-PATROL BOAT C23