Archive for the ‘Times of Malta’ Category

-

LIGHTS OUT FOR CHRISTMAS

Christmas time and the days preceding it are generally associated with colour, light, optimism and fun. Yet this was not the case in 1939 when the Christmas season became synonymous with gloom, darkness, uncertainty and fear.

On 18 September 1939, a table showing the duration of the ‘Official Night’ was published in Government Notice No. 459 in The Malta Government Gazette. This table included each day of each month and the beginning and end of what was to be considered as the official night hours. Such instructions formed part of the Malta Defence Regulations, 1939, which aimed to protect the Maltese Islands and its inhabitants as World War II ravaged in other countries.

Two days later, on 20 September 1939, Government Notice No. 473 issued the Lights Restriction Order which was effective from that day. The directions of this Order had to be observed between midnight and 4:30am on every day of the week, and also between 10:00pm and midnight on Fridays. During these times, all lights in any building had to be masked to be invisible from the sea and from the air. No lights, other than lights authorised by the competent authority, were permitted in any open spaces whether private or public, in yards, roofs or open verandas. The use of illuminated lettering or signs in any shops were prohibited unless authorised by the Commissioner of Police or the competent authority. The traffic of motor vehicles during these hours was banned and any vehicles which did not comply with these provisions could be stopped and detained until 6:00am. Obviously, all fireworks were also prohibited.

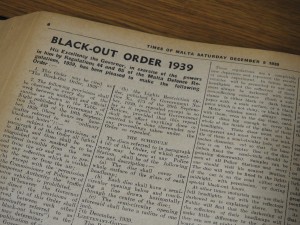

Two days later, on 20 September 1939, Government Notice No. 473 issued the Lights Restriction Order which was effective from that day. The directions of this Order had to be observed between midnight and 4:30am on every day of the week, and also between 10:00pm and midnight on Fridays. During these times, all lights in any building had to be masked to be invisible from the sea and from the air. No lights, other than lights authorised by the competent authority, were permitted in any open spaces whether private or public, in yards, roofs or open verandas. The use of illuminated lettering or signs in any shops were prohibited unless authorised by the Commissioner of Police or the competent authority. The traffic of motor vehicles during these hours was banned and any vehicles which did not comply with these provisions could be stopped and detained until 6:00am. Obviously, all fireworks were also prohibited. An Air-Raid Precautions Order was communicated in Government Notice No. 504 on 4 October 1939. Eventually on 9 December 1939, The Times of Malta published the provisions of The Black-Out Order, 1939, which had to be observed on every day of the week between midnight and the official sunrise. During these hours, all the lights on the Islands had to be extinguished or masked as to be rendered invisible from the sea and from the air. Special Black-Out hours could also be determined when necessary.

An Air-Raid Precautions Order was communicated in Government Notice No. 504 on 4 October 1939. Eventually on 9 December 1939, The Times of Malta published the provisions of The Black-Out Order, 1939, which had to be observed on every day of the week between midnight and the official sunrise. During these hours, all the lights on the Islands had to be extinguished or masked as to be rendered invisible from the sea and from the air. Special Black-Out hours could also be determined when necessary. As part of the Black-Out Order, from 14 December 1939, all motor vehicles which had to travel at night, other than those belonging to His Majesty’s service, had to have their bulbs removed from their lamps. Opaque cardboard discs were to be fixed to the lights of the vehicles and the reflectors’ surface had to be covered with a non-reflecting substance. A white disc had to be affixed at the back of all motor vehicles at a height of three feet from the ground to make them visible on the roads. Traffic of motor vehicles during the black-out was prohibited except for those who obtained permission from the Commissioner of Police or a competent authority.

Another notice which appeared on The Times of Malta of the 9 December 1939 urged the inhabitants to comply with these regulations for their own safety. People were recommended to stay at home and to avoid going out in the darkness. Those who needed to get out were advised to walk on the right-hand side of the road to face oncoming traffic and to carry with them a white object to make them more visible to drivers. Owners of goats were informed to keep their animals off the road at night. On the other hand, drivers were cautioned to drive very slowly and with great care.

Measures were being taken to prepare the people how to take the necessary precautions in preparation of an expected war. Black-outs intended to prevent crews of enemy aircraft from being able to identify their targets by sight. Nonetheless, these precautionary provisions proved to be one of the more unpleasant aspects of war, disrupting many civilian activities and causing widespread grumbling and lower morale.

The Times of Malta of 13 December 1939 reports that some misapprehension had arisen among that section of the public who had to rise early for work and travel by early buses, since it was not clear at what time the bus service started. Indeed, all buses were to continue their usual service provided that they adhered to the regulations regarding headlights and lights, including the inside of the vehicles which had to remain in darkness.

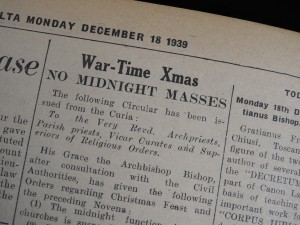

Even though the Maltese Islands were not yet directly involved in war, a foreboding atmosphere crept its way into the lives of people. As if matters were not yet miserable enough, a Bishop’s Circular which was published on The Times of Malta of 17 December 1939 declared that the Christmas midnight function in the churches was to be suspended. The Novena and feast functions could be celebrated from 4:00am onwards provided that no lights were visible from the outside. Those churches which required singers and musicians from far places for the early Christmas function had to apply to the Commissioner of Police for the necessary permits to travel. While it was permissible to give a small sign to the faithful by the ringing of bells for the function of the Novena and Christmas Eve, this had to be done according to predetermined rules.

Even though the Maltese Islands were not yet directly involved in war, a foreboding atmosphere crept its way into the lives of people. As if matters were not yet miserable enough, a Bishop’s Circular which was published on The Times of Malta of 17 December 1939 declared that the Christmas midnight function in the churches was to be suspended. The Novena and feast functions could be celebrated from 4:00am onwards provided that no lights were visible from the outside. Those churches which required singers and musicians from far places for the early Christmas function had to apply to the Commissioner of Police for the necessary permits to travel. While it was permissible to give a small sign to the faithful by the ringing of bells for the function of the Novena and Christmas Eve, this had to be done according to predetermined rules.Albeit the continuous warnings and pleas to adhere strictly to the black-out orders, it seemed that not everyone was following the rules. An announcement on The Times of Malta of the 20 December 1939 issued by the Lieutenant’s Government Office advised the public that the black-out on the night of December 15-16 was not entirely satisfactory, and that there were several lights showing in the Valletta, Sliema, Hamrun, Cospicua and Naxxar districts. Several lights were only put out as aircraft passed overhead. This notice pointed out also that a section of the public could still have been unaware of the black-out rules since they seemed to have been published only on The Times of Malta and Il-Berqa newspapers. Illiterate persons would therefore have had no way of being forewarned except by hearsay. Therefore, a siren warning which was different from the Air-Raid alarm signal, was recommended to be given throughout the islands at sunset.

Letters by readers in the Correspondence section of The Times of Malta of the 20 and 21 December 1939 vent their frustration and contempt at those who were not taking these black-out precautions seriously:

“Many people rather irresponsibly remark that they do not quite see the use of strict black-outs when Germany is at such a distance away. The reply is that precaution is better than cure. I am sure that these people will think very different if they find one day a German bomb dropping at their door-step or in their backyard, just because some stray lights guided an enemy to an objective.” Signed ‘Common-Sense’.

“I am sure that a number of law-abiding citizens in these islands feel that the time has come for coercion to replace coaxing. Those people who scorn to comply with reasonable regulations are either knaves or fools and most dangerous to the community in war time; they should be under lock and key for the duration of the war: either in jail or in a lunatic asylum. The pathetic appeals made by the authorities are becoming nauseating.” Signed Lieutenant Colonel (retired) H. M Marshall.

Special Black-Out arrangements for Christmas and New Year, published on The Times of Malta of the 23 and 30 December 1939, informed the public that the black-out of buildings on the nights of 24 – 27 December and 30 December – 1 January were to be postponed for one and a half hours from midnight. On these nights, motor vehicles were allowed on the road without requiring special permission until 1:30am, and shops and places of entertainment could remain open until 1:00am.

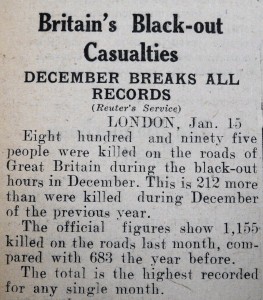

Special Black-Out arrangements for Christmas and New Year, published on The Times of Malta of the 23 and 30 December 1939, informed the public that the black-out of buildings on the nights of 24 – 27 December and 30 December – 1 January were to be postponed for one and a half hours from midnight. On these nights, motor vehicles were allowed on the road without requiring special permission until 1:30am, and shops and places of entertainment could remain open until 1:00am. Possibly few had considered that light could be their enemy until it became essential to extinguish it. There was no mention of accidents or fatalities due to the black-out on the Islands in the December’s Times of Malta newspapers. However, reports from Great Britain relating to the high increase in road fatalities during the night were quite shocking. On 13 December 1939, the British Official Press stated that road fatalities had increased considerably from September to November. Yet the worst scenario took place in December, as reported by the Reuter’s Service on 16 January 1940, when 895 people were killed on the roads of Great Britain during the black-out hours. This was 212 more than those who were killed during December of the previous year.

Possibly few had considered that light could be their enemy until it became essential to extinguish it. There was no mention of accidents or fatalities due to the black-out on the Islands in the December’s Times of Malta newspapers. However, reports from Great Britain relating to the high increase in road fatalities during the night were quite shocking. On 13 December 1939, the British Official Press stated that road fatalities had increased considerably from September to November. Yet the worst scenario took place in December, as reported by the Reuter’s Service on 16 January 1940, when 895 people were killed on the roads of Great Britain during the black-out hours. This was 212 more than those who were killed during December of the previous year.This was surely a strange Christmas to the Maltese people who are accustomed to celebrate these days in a profuse way. Although through no fault of their own, they were involved in war and they had to adapt to war conditions. Alas, much worse was yet to come.

(This article was published in the Christmas Times magazine issued with The Times of Malta dated 13 December 2017)

-

KONTINENT IEĦOR

“F’żogħżiti l-Awstralja kienet meqjusa bħala dinja tal-ħolm, dinja ta’ opportunitajiet li ma kellniex f’pajjiżna. Ironikament it-tmiem tat-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija nissel problema ta’ qgħad kbir fil-gżejjer Maltin u speċjalment iż-żgħażagħ bdew jaħarquhom saqajhom biex jitilqu minn fuq din l-art ħalli jfittxu xortihom x’imkien ieħor. Jien kont waħda minn dawk iż-żgħażagħ li flimkien ma’ żewġ ħuti erħejnielha lejn dan il-kontinent b’sens qawwi ta’ avventura. Imma ġaladarba sibt ruħi hemm irrealizzajt x’kont napprezza tassew f’ħajti u dan kollu kien qiegħed f’art twelidi.”

“F’żogħżiti l-Awstralja kienet meqjusa bħala dinja tal-ħolm, dinja ta’ opportunitajiet li ma kellniex f’pajjiżna. Ironikament it-tmiem tat-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija nissel problema ta’ qgħad kbir fil-gżejjer Maltin u speċjalment iż-żgħażagħ bdew jaħarquhom saqajhom biex jitilqu minn fuq din l-art ħalli jfittxu xortihom x’imkien ieħor. Jien kont waħda minn dawk iż-żgħażagħ li flimkien ma’ żewġ ħuti erħejnielha lejn dan il-kontinent b’sens qawwi ta’ avventura. Imma ġaladarba sibt ruħi hemm irrealizzajt x’kont napprezza tassew f’ħajti u dan kollu kien qiegħed f’art twelidi.”Trabbejt nisma’ dawn ir-rakkonti t’ommi Angela Busuttil peress li spiss kienet issemmi ż-żminijiet li għexet fl-Awstralja. Barra minn hekk, minħabba li wieħed minn ħutha kien għadu jgħix hemmhekk, mhux darba u tnejn li n-nanna Fortunata Abela u z-zija Gracie Cilia talbuni biex niktbilhom xi ittra ħalli jibgħatuhielu. Niftakar li kienu ittri li kollha jibdew l-istess “Għażiż Ġużeppi, Vera u t-tfal, nispera li tinsabu tajbin bħal kif ninsabu aħna għall-grazzja t’Alla”.

Kont tgħallimt nikteb l-introduzzjoni bl-amment u kont nitbissem meta nara li dejjem kienu jiktbulu l-istess ħaġa. Il-bqija tal-ittri kienu jikkonsistu f’dak li jkunu għaddew minnu matul dawk l-aħħar ġimgħat jew dwar xi ħaġa li kienu beħsiebhom jagħmlu. Ta’ tifla li kont, ftit stajt napprezza dawk l-ittri ripetittivi. Kellhom jgħaddu ħafna snin qabel fhimt kemm kienu jfissru għalihom dawk il-karti ċelesti li kont niktbilhom l-ittri fuqhom u għaliex kienu jistennew ir-risposti tagħhom tant b’ħerqa. Ir-raġuni kienet dejjem spjegata ċara fir-rakkonti t’ommi. Imma kultant jekk ma ġġarrabx, għajnejk ma jinfetħux. Illum li jiena sirt omm u li s-snin gerrbu fuq ommi wkoll, kapaċi nixtarr aktar.

“Kien ħija l-kbir Ġużeppi li beda jħeġġiġna biex immorru l-Awstralja. Hu kien diġà miżżewweġ u kellu l-familja tiegħu. Jien kien għad kelli 17 il-sena, ommi ma riditnix immur, u missieri ma ried jagħti b’xejn il-kunsens tiegħu biex insiefer. Imma meta għalaqt it-18 il-sena, Ġużeppi rnexxielu jikkonvinċi lil missieri li kien ser jieħu ħsiebi hu. Wegħdu li ser iġib ruħu daqs li kieku kien it-tieni missier tiegħi u kelmtu żammha għax id-dixxiplina tiegħu kienet iebsa mhux ħażin!”

“Kien ħija l-kbir Ġużeppi li beda jħeġġiġna biex immorru l-Awstralja. Hu kien diġà miżżewweġ u kellu l-familja tiegħu. Jien kien għad kelli 17 il-sena, ommi ma riditnix immur, u missieri ma ried jagħti b’xejn il-kunsens tiegħu biex insiefer. Imma meta għalaqt it-18 il-sena, Ġużeppi rnexxielu jikkonvinċi lil missieri li kien ser jieħu ħsiebi hu. Wegħdu li ser iġib ruħu daqs li kieku kien it-tieni missier tiegħi u kelmtu żammha għax id-dixxiplina tiegħu kienet iebsa mhux ħażin!”“Bilkemm niftakar kif saru l-preparazzjonijiet bil-ġenn li kelli biex nitlaq. Bsart li ser nimmissja lill-ġenituri tiegħi u lil ħuti l-oħra. Imma ta’ żagħżugħa li kont neħħejt dawk il-ħsibijiet minn quddiem għajnejja u minflok intfajt noħlom dwar dik l-opportunità sabiħa li ngħix u naħdem f’pajjiż ieħor. Dakinhar li tlaqna biex nibdew dan il-vjaġġ, ommi għafsitni magħha u reġgħet qaltli li ma xtaqitnix immur. Il-ħsieb tal-firda minni kien diġà qed ikiddha iżda meta ratni konvinta biex insiefer, talbitni biex ma ninsihiex u biex ma nibqax hemm. Madanakollu jien moħħi kien biss f’dak il-vapur sabiħ li kien qed jistenniena biex jeħodna lejn l-Awstralja.”

“Għal dan il-vjaġġ konna jiena, ħija Indrì u ħija Ġużeppi bil-familja tiegħu. Morna b’vapur lussuż, l-Angelina Lauro. Il-kmamar kienu spazzjużi u komdi. Ħallasna biss Lm10 kull wieħed biex vjaġġajna għal xahar sħiħ fuqu. Kien hemm ħafna Maltin oħra u kollha konna stmati tajjeb ħafna. Il-vjaġġ kien interessanti u pjaċevoli sakemm wasalna f’Port Said fil-Baħar l-Aħmar u nqbadna f’maltemp kbir. F’daqqa waħda kollox beda jitkaxkar ‘l hawn u ‘l hemm: l-imwejjed, is-siġġijiet, is-sodod. Tal-biża’! Ħafna mill-passiġġieri kellhom jingħataw il-mediċini għax ħassewhom ma jifilħux. Lili kieku m’għamilli xejn il-baħar imma ħassejtni tterrorizzata. Wara dakinhar bosta kienu b’qalbhom imtaqtqa kif ser naslu l-Awstralja għax il-vjaġġ donnu ma ried jispiċċa qatt! Niftakar li l-klieb il-baħar baqgħu jsegwuna matul il-vjaġġ kollu, dejjem jistennew lill-ħaddiema ta’ fuq il-vapur biex jarmu l-fdalijiet tal-ikel fil-baħar.”

“Malli wasalna Melbourne laqagħna temp imsaħħab u xejn ma ħadt grazzja mal-post. Xi ħbieb li kienu qed jistennewna ħaduna Adelaide li kien jumejn bogħod bil-karozza. Hemmhekk għamilna ftit taż-żmien. Kien post kwiet u ma tantx kien hemm xogħol. Tlaqna u morna Sydney, niġru minn xogħol għall-ieħor. Niftakar li l-ewwel darba li mort għax-xogħol, tlajt fi tren u marret għajni bija, u t-tren baqgħet sejra bija f’post ieħor. Tgħidx kemm bżajt meta stenbaħt u ma kontx naf x’se naqbad nagħmel. Tinkwieta għax la ma tkunx taf il-post, ma tafx ma’ min tista’ tiltaqa’. Ħdimt f’żewġ fabbriki imma ma nista’ ninsa qatt kemm laqgħuni b’mod sabiħ fl-ewwel fabbrika li dħalt fiha. Kont ilni naħdem hemm ftit ġranet biss u hekk kif skoprew li kont għadni kif għalaqt it-18 il-sena għamluli surprise party u tgħidx kemm tawni rigali! Lanqas wara għaxar snin xogħol ma jagħmlulek hekk f’Malta!”

“Malli wasalna Melbourne laqagħna temp imsaħħab u xejn ma ħadt grazzja mal-post. Xi ħbieb li kienu qed jistennewna ħaduna Adelaide li kien jumejn bogħod bil-karozza. Hemmhekk għamilna ftit taż-żmien. Kien post kwiet u ma tantx kien hemm xogħol. Tlaqna u morna Sydney, niġru minn xogħol għall-ieħor. Niftakar li l-ewwel darba li mort għax-xogħol, tlajt fi tren u marret għajni bija, u t-tren baqgħet sejra bija f’post ieħor. Tgħidx kemm bżajt meta stenbaħt u ma kontx naf x’se naqbad nagħmel. Tinkwieta għax la ma tkunx taf il-post, ma tafx ma’ min tista’ tiltaqa’. Ħdimt f’żewġ fabbriki imma ma nista’ ninsa qatt kemm laqgħuni b’mod sabiħ fl-ewwel fabbrika li dħalt fiha. Kont ilni naħdem hemm ftit ġranet biss u hekk kif skoprew li kont għadni kif għalaqt it-18 il-sena għamluli surprise party u tgħidx kemm tawni rigali! Lanqas wara għaxar snin xogħol ma jagħmlulek hekk f’Malta!”“L-Awstralja kienet tgħaġġibni bil-kobor tagħha. Kienet sabiħa ħafna b’siġar twal u b’għelieqi spazzjużi u b’toroq li ma jispiċċaw qatt. Ġieli rajt ukoll xi annimali tal-post, l-aktar il-kangaroos kbar li mhux darba u tnejn fettlilhom jintasbu f’nofs ta’ triq u ma jkunu jridu jwarrbu b’xejn biex ngħaddu bil-karozza. Konna noqogħdu Greenacre fejn krejna dar pjuttost kbira. Ma tantx kien hemm Maltin. Kellna familja aboriġina fost il-ġirien tagħna u t-tfal tagħhom kienu jiġu jilgħabu magħna. Madwarna kienu joqgħodu nies minn kull pajjiż.”

“Kien hemm okkażżjonijiet fejn konna noħorġu xi ftit. Niftakar li ġieli morna naraw ir-wrestling. Kien ikollna l-ġellied favorit tagħna u erħilna ngħajjtu kemm nifilħu meta jibda jaqla’ xi daqqtejn sew mingħand l-ieħor. Konna nidħlu b’vuċi tajba u noħorġu maħnuqin imma konna nieħdu gost. Dejjem bqajt bil-kurżità jekk kienux ikunu qed jiġġieldu veru jew le. Tant kienu jaqilgħu li ma stajtx nemmen li kienu jagħtu bis-serjetà!”

“Kien hemm okkażżjonijiet fejn konna noħorġu xi ftit. Niftakar li ġieli morna naraw ir-wrestling. Kien ikollna l-ġellied favorit tagħna u erħilna ngħajjtu kemm nifilħu meta jibda jaqla’ xi daqqtejn sew mingħand l-ieħor. Konna nidħlu b’vuċi tajba u noħorġu maħnuqin imma konna nieħdu gost. Dejjem bqajt bil-kurżità jekk kienux ikunu qed jiġġieldu veru jew le. Tant kienu jaqilgħu li ma stajtx nemmen li kienu jagħtu bis-serjetà!”“Il-kobor tal-post kien jaqtgħalna qalbna biex nimirħu ‘l bogħod. U l-biċċa l-kbira minn ħajjitna kienet iddedikata biss għax-xogħol. Agħar minn hekk, ommna spiss kienet tibgħatilna l-ittri jew xi casette irrekordjatha bil-vuċi tagħha fejn kienet twissina biex noqogħdu attenti ħalli ma nweġġgħux u b’mod speċjali, biex ma niżżewġux hemmhekk. “Fittxu ejjew ‘l hawn, ejjew lura,” kienet dejjem tirrepeti. Kemm tiflaħ tisma’ kliem bħal dan?”

“Ma domnix ma bdejna niddejqu u nixxenqu biex nirritornaw lejn pajjiżna fejn fiċ-ċokon tiegħu kellna dak kollu li ridna. Il-problema kienet li għalkemm biex morna l-Awstralja kellna nħallsu biss Lm10 kull wieħed, biex naqbdu vapur lura lejn Malta l-prezz kien Lm250 kull ras. Għamilna sentejn u nofs ngħixu hemm sakemm irnexxielna nfaddlu biżżejjed flus għalina kollha. Ġejna lura Malta bil-vapur Achille Lauro u mill-ġdid domna xahar nivvjaġġaw.”

“Kont kuntenta li rajt pajjiż ieħor imma ddispjaċini ħafna li tlaqt il-familja tiegħi. Ħadt ir-ruħ hekk kif wasalna lura Malta u rajthom kollha qawwijin u sħaħ. Tgħidx kemm għannaqthom u kien f’dak il-ħin li rrealizzajt kemm kont immissjajthom. “Ma nerġax nitla’ ma. Ma nerġax nitilqek,” wegħedt lil ommi hekk kif għafastha miegħi. U kelmti żammejtha.”

“Kont kuntenta li rajt pajjiż ieħor imma ddispjaċini ħafna li tlaqt il-familja tiegħi. Ħadt ir-ruħ hekk kif wasalna lura Malta u rajthom kollha qawwijin u sħaħ. Tgħidx kemm għannaqthom u kien f’dak il-ħin li rrealizzajt kemm kont immissjajthom. “Ma nerġax nitla’ ma. Ma nerġax nitilqek,” wegħedt lil ommi hekk kif għafastha miegħi. U kelmti żammejtha.”Wara xi snin, ħuha Ġużeppi reġa’ tela’ l-Awstralja bil-familja tiegħu fejn dam għal żmien twil sakemm eventwalment, ta’ età kbira rritorna Malta. Illum m’għadnix nikteb l-ittri fuq il-karti ċelesti. In-nanna, iz-zija u z-ziju ħallewna u issa fadal biss il-memorja tagħhom.

(Dan l-artiklu ġie ppubblikat fis-Senior Times li ħareġ mal-ġurnal The Times of Malta tas-17 ta’ Novembru 2017)

-

Walk this way

When there is such a wide selection of travel destinations, why should one opt to go on a pilgrimage?

“I did ask that question to myself on the first day of my Camino,” revealed Matthias Ebejer. “The walk to Santiago de Compostela in northwest Spain is not a travel holiday like many others. It can be quite a shock for those who are not used to outdoor activities such as hiking, trekking or camping. On the other hand, it can prove to be pretty challenging to find the real meaning of it all if one is regularly accustomed to such adventures.”

“I did ask that question to myself on the first day of my Camino,” revealed Matthias Ebejer. “The walk to Santiago de Compostela in northwest Spain is not a travel holiday like many others. It can be quite a shock for those who are not used to outdoor activities such as hiking, trekking or camping. On the other hand, it can prove to be pretty challenging to find the real meaning of it all if one is regularly accustomed to such adventures.”Matthias was definitely not one of the latter. He was enticed to go on this pilgrimage by his girlfriend Deborah since she had already experienced it together with her family.

“It did not take her much to convince me. As I began to look for information about this walk, I realized that this was the perfect way to get to know Spain closely. Such a pilgrimage gives you the opportunity to walk from one village to another, crossing different regions, meeting all sorts of people and learning about their culture and the places’s history. It is also very interesting to observe the changing architectural styles, cuisine forms, and people’s mentalities as you move along the rural areas which turn into urban locations as you get closer to the final destination.”

As a historian specializing in the history of the Knights Hospitallers of the Order of St John, Matthias had a further motive to try out this pilgrimage.

As a historian specializing in the history of the Knights Hospitallers of the Order of St John, Matthias had a further motive to try out this pilgrimage.“The Order was established to provide care for the sick, poor or injured pilgrims who visited the Holy Land. Yet eventually, these knights were also protecting the Christian pilgrims who travelled the St James’ Way to Santiago de Compostela. They constructed cathedrals, monasteries and pilgrims’ hostels along the route, some of which still exist today, such as the Cathedral of Portomarin, my favourite stop along the Camino. Portomarin was originally a Hospitaller commandery, and it indicated the part of the walk which was guarded by the Knights of St John. Pilgrim museums located in the various villages and towns along the Camino are quite informative and inspiring. A number of them are found within small churches or large cathedrals but one can also visit private houses which used to belong to wealthy pilgrims who donated their dwellings to become museums.”

Although Santiago de Compostela has been associated with spirituality since olden times, it was the miraculous discovery of the remains of the apostle James in the ninth century in this area which made this Galician town so popular. These remains were buried in the site upon which the renowned cathedral of this town was later built.

Although Santiago de Compostela has been associated with spirituality since olden times, it was the miraculous discovery of the remains of the apostle James in the ninth century in this area which made this Galician town so popular. These remains were buried in the site upon which the renowned cathedral of this town was later built.“The authenticity of this legend has often created disputes in the Catholic Church since there are those who have their doubts about who is really buried in the crypt of this cathedral. Nevertheless, I believe that such controversy is superfluous because independently of who is buried within the silver box that lies at the heart of this holy site, the ultimate goal of each pilgrim is to stop there and meditate about the journey made and to liberate oneself from the troubling baggage of problems that one has carried along in order to come out as a new person.”

Thousands of pilgrims have walked this path for the last one thousand years and yet ‘the way’ is a very personal journey.

“I am a Catholic, however I am not a religious person. I must admit that my original aim for this walk was more based on cultural interest rather than a spiritual one. Yet such pilgrimages are full of surprises and my walk ended up giving me much more than that.”

“I am a Catholic, however I am not a religious person. I must admit that my original aim for this walk was more based on cultural interest rather than a spiritual one. Yet such pilgrimages are full of surprises and my walk ended up giving me much more than that.”The origin of such pilgrimages was generally based on sacrifice and repentance from one’s sins. Nowadays, things have changed and the aim for such an experience depends on each individual.

“This pilgrimage is not necessarily meant to be a sacrifice. One is not expected to suffer or to be in pain. I must say that today such a pilgrimage is more a reaction to that universal urge to leave the safety of home in order to find oneself. One has several options from where to start this pilgrimage and each have different levels of difficulties. The longest and most popular route is the Camino Francés which stretches 780 km from St. Jean-Pied-du-Port near Biarritz in France to Santiago.”

Matthew has participated two times in the Camino. The first time was 213 kms long, leaving from Ponferrada in Spain and taking 9 days to finish. The second one was 100 kms long, being the minimum distance, leaving from Sarria and taking 5 days to arrive to Santiago de Compostela.

“Each time I went with a group of friends. The Camino we chose was not difficult and we walked about 20 to 25 kms daily. Friends provide good company and they also help you to go on whenever you might feel discouraged or tempted to stop. The walk was always deeply moving and enriching. Travelling on foot provides you with the leisure to look around you, to feel the earth beneath your feet, to breathe the fresh air and enjoy the various scents of the surrounding landscapes, and to listen to the sounds or relish the silence. It also presents you with those significant moments wherein you are walking alone thinking about your life, the decisions you made or are about to make, and the meaning of living itself. Although initially one might start this pilgrimage as a mere tourist, at the end of it one will recognize a considerable change in oneself.”

“Each time I went with a group of friends. The Camino we chose was not difficult and we walked about 20 to 25 kms daily. Friends provide good company and they also help you to go on whenever you might feel discouraged or tempted to stop. The walk was always deeply moving and enriching. Travelling on foot provides you with the leisure to look around you, to feel the earth beneath your feet, to breathe the fresh air and enjoy the various scents of the surrounding landscapes, and to listen to the sounds or relish the silence. It also presents you with those significant moments wherein you are walking alone thinking about your life, the decisions you made or are about to make, and the meaning of living itself. Although initially one might start this pilgrimage as a mere tourist, at the end of it one will recognize a considerable change in oneself.”During his research, Matthew discovered that even the kings of Spain participated in the Camino as part of an old tradition. Later on, during the walk he was informed that up to the present days, prisoners who have a good conduct are offered the opportunity to spend the last six months of their sentence walking the Camino with a guardian instead of spending them in prison.

“You meet several people along this pilgrimage and you get the privilege to listen to their stories about why they chose to do this walk. Some of these narratives are very touching such as that of the Scandinavian eighty-year old man who had lost his wife some years before. As he walked part of the way with me, he told me how he had become very depressed by her death and had given up on life, waiting for his end to come soon. Then one day, he decided to stop mourning and to regain the joy of life again. After seeking help from a travel agency, he was recommended to try out the Camino and there he was seeking a way to turn a new page in his life.”

“You meet several people along this pilgrimage and you get the privilege to listen to their stories about why they chose to do this walk. Some of these narratives are very touching such as that of the Scandinavian eighty-year old man who had lost his wife some years before. As he walked part of the way with me, he told me how he had become very depressed by her death and had given up on life, waiting for his end to come soon. Then one day, he decided to stop mourning and to regain the joy of life again. After seeking help from a travel agency, he was recommended to try out the Camino and there he was seeking a way to turn a new page in his life.”One can choose the level of comfort and also the means how to do this pilgrimage. Hostels, hotels, restaurants, bars and shops are available all along the route which one can travel by walking, cycling, horse riding or even by car, although the latter does not count much.

“When you decide which route you are going to take, you can buy a guidebook online and prepare your journey beforehand. These guidebooks will provide you with all the required information and also with recommendations where to stop. We used to start walking very early in the morning when it was still dark. After a 3km walk, we would stop to eat breakfast and then continue along the way for a further 17kms until we reached the next village or town, generally at around 12:30pm. We chose to rest at municipal hostels wherein we could take a shower, cook some food in the kitchen, wash our clothes and sleep in the dormitory for the price of 5 euros. Such an arrangement gave us the opportunity to visit the village or town in which we stopped or to eat a good meal at a restaurant whenever we felt like it.”

“When you decide which route you are going to take, you can buy a guidebook online and prepare your journey beforehand. These guidebooks will provide you with all the required information and also with recommendations where to stop. We used to start walking very early in the morning when it was still dark. After a 3km walk, we would stop to eat breakfast and then continue along the way for a further 17kms until we reached the next village or town, generally at around 12:30pm. We chose to rest at municipal hostels wherein we could take a shower, cook some food in the kitchen, wash our clothes and sleep in the dormitory for the price of 5 euros. Such an arrangement gave us the opportunity to visit the village or town in which we stopped or to eat a good meal at a restaurant whenever we felt like it.”“The secret is to travel as light as possible and to learn to live with the barest minimum. To cater for the changing weather, one should carry basic layering of clothing and everything should be waterproof. A first-aid kit which includes talc, cream against sores and adhesive bandages is a must. A torch is necessary to find the way in the dark. One must not forget to take any required medicine and also a medical prescription in case something happens to it. Ear plugs could be helpful when sleeping in dormitories. However one of the most important items is a comfortable and sturdy pair of shoes.”

One should definitely not do this pilgrimage without carrying a pilgrim passport or credencial along with him.

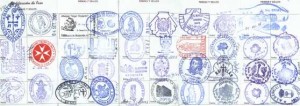

One should definitely not do this pilgrimage without carrying a pilgrim passport or credencial along with him.“We obtained our credencial from the Curia of Madrid. This is a blank passport which one stamps along the way in order to confirm one’s participation in the pilgrimage. Many places are equipped with their unique Camino stamps along the route and we loved to go in search of the most appealing ones. When presented duly stamped at Santiago de Compostela, each pilgrim is given a certificate and a plenary indulgence. Eventually, this credencial becomes a very dear memento of this journey.”

“Two other things which should be obtained before starting the walk is the pilgrims’ scallop shell and walking stick. We also placed a Maltese flag on our backpack and this was always a good conversation starter with other pilgrims. At the end of our pilgrimage, we made it a point to arrive in Santiago in time for the noon pilgrims’ mass where we received the blessing. Although we had walked for 20 kms, this experience was so uplifting and emotional that we felt no fatigue even though we had to stand up for an hour and a half as the cathedral was packed with people.”

“Two other things which should be obtained before starting the walk is the pilgrims’ scallop shell and walking stick. We also placed a Maltese flag on our backpack and this was always a good conversation starter with other pilgrims. At the end of our pilgrimage, we made it a point to arrive in Santiago in time for the noon pilgrims’ mass where we received the blessing. Although we had walked for 20 kms, this experience was so uplifting and emotional that we felt no fatigue even though we had to stand up for an hour and a half as the cathedral was packed with people.”Matthew’s first pilgrimage ended at Finisterre and the second at La Coruna.

“Pilgrims used to walk another three to five days to reach the shores of Finisterre and Muxia, at the extreme point of Spain facing the Atlantic, the edge of the known world. There they would collect the scallop shells as a sign that they had walked the Camino. Legend has it that the body of St James was brought back from Jerusalem from these shores.”

“Pilgrims used to walk another three to five days to reach the shores of Finisterre and Muxia, at the extreme point of Spain facing the Atlantic, the edge of the known world. There they would collect the scallop shells as a sign that they had walked the Camino. Legend has it that the body of St James was brought back from Jerusalem from these shores.”“At Finisterre there is the tradition to throw away the walking stick which has accompanied you along your pilgrimage into the sea and then burn some of your clothes. This symbolically means that you have walked the way, that you have searched for answers and found them, and that now you are leaving the pilgrim’s life behind in order to go on with your life.”

(This article was published in the Travel Supplement issued with The Times of Malta dated 29th March 2017)

-

A sea of profits

A search through historical notarial deeds reveals how Maltese businesses exploited the cruel reality of war and slavery, maritime historian Dr Joan Abela tells Fiona Vella.

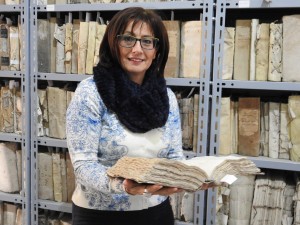

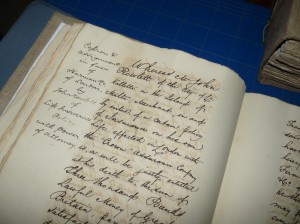

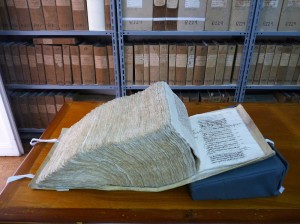

“Even though there are people who might think that the human tragedy which we are experiencing today in the Mediterranean Sea may be something contemporary, in reality, the human element has always been an issue in this region,” Dr Joan Abela says as she refers me to some thick manuscripts that she had set aside at the Notarial Archives in Valletta.

“Even though there are people who might think that the human tragedy which we are experiencing today in the Mediterranean Sea may be something contemporary, in reality, the human element has always been an issue in this region,” Dr Joan Abela says as she refers me to some thick manuscripts that she had set aside at the Notarial Archives in Valletta.We had agreed to discuss the dreadful reality of slavery in the old days and these manuscripts are witness to this phenomenon which took place even in our islands.

“Before the Knights of St John came to Malta in 1530, the Maltese Islands were already involved in the enslavement business and this was quite a legitimate affair at the time. People captured as slaves or captives were considered as commodities and their negotiations were regarded as valuable transactions, which when necessary, were also recorded in notarial deeds.”

Dr Abela continued to inform me that in that era, the traffic of slaves occupied a prime place in the economic activity of maritime trade in the southern Mediterranean since it allowed the profitable exchange of monies and commodities.

“Well aware of the strategic geographical location of Malta in the slave trade business, the Knights of St John established a strong infrastructure in order to attract more merchants and agents. Those who stopped at our islands would have been able to replenish their ships and to make use of the excellent and accomodating financial services which included the availability of notaries, agents, and money changers. Indeed, Braudel stated that Malta together with Livorno acted as a central hub for the slave trade.”

One needed to have a special license to work as a corsair, otherwise he would be regarded as a pirate and could be hanged for capturing ships, cargo or people illegally.

“Since corsairing could render ample returns, people invested in it and received their respective shares from the bounty that the corsairs brought with them after they seized a ship. Investors consisted mainly of businessmen and knights. However, one would also find the Jerosolimitan Nuns of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St John which were located in St Ursula Street, Valletta, forming part of these investors. Their share was due to them for their role in praying for the safe return of the corsairs.”

“Since corsairing could render ample returns, people invested in it and received their respective shares from the bounty that the corsairs brought with them after they seized a ship. Investors consisted mainly of businessmen and knights. However, one would also find the Jerosolimitan Nuns of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St John which were located in St Ursula Street, Valletta, forming part of these investors. Their share was due to them for their role in praying for the safe return of the corsairs.”As Dr Abela began to indicate various episodes from the displayed manuscripts, she admitted that she was often very touched by what she read in those pages.

“Obviously when one looks at history in a collective manner, one would say that there was this particular circumstance taking place during that period and that is it. Yet when one looks into these documents and starts reading a deed about an individual life, one starts empathizing with that person and many questions will come to mind. For example, I came upon a deed wherein a priest was selling a slave together with her son to a Genovese merchant on condition that the latter would baptise the child on that same day. The merchant agreed and the deal was made. When you read something like this, how can you help not wonder who this woman was and from where she had come?”

Corsairing was a high risk job but if all went well, those involved could become rich overnight.

“Men craved for the opportunity to become corsairs and at one point, there were so many men leaving their jobs to join corsair ships that the Maltese Universitas requested the King of Spain to restrain this because the island was at a loss with the local workforce.”

“Not all the captured ships delivered the same profits. A galley of the Sultan which would have been filled with riches and fine cloth, would be precious but not without issues and trouble. Other ships would be carrying worthy cargo such as sugar or wheat. Nonetheless, it was the human cargo which was considered the most profitable.”

Captured people could be sold as slaves or held as captives until they were ransomed.

“The whole process for redemption was very complicated. These contracts unravel all this system including how the involved parties went about to assure the best positive outcome from their deal. An agent would be requested to act as an intermediary between one party and the other, taking responsibility to collect a deposit from the captive and then to take him to an agreed destination in order to collect the rest of the money from his relatives and then release him.”

“In April 1558, a slave, Busert Bin Hahmet de Casar concluded the following agreement with his master Giuseppe Baldagno. Busert was transferred to Antonio de Banda from Messina who was a patrone of a ship belonging to Marco Antonio Delixandro, also from Messina. The ship was equipped to undertake a voyage to the Tripolitan fortress of Barbaria. Antonio was to conduct the slave to Tripoli, and from there retrieve 80 gold ducats which was the stipulated price for redemption. This amount was to be remitted either in their value in dinars or in oil, wool or leather goods which the Arabs sold inside the Tripolitan fortress, which goods would be exempt from duty. Busert promised to pay Giuseppe within twenty days of his arrival at the fortress, on condition that the patrone was not to let him disembark unless he received the said payment or its value in goods. Once arrived at destination, the slave would need to make the necessary connection with an intermediary in his own country who would be in a position to acquire the redemption money or goods for him. Once the sum was settled, the slave would become a free man, but if the sum was not paid, he was to return with the same ship and consigned back to his master Giuseppe.”

At times, the Grand Master had to issue a safe conduct certificate to enemy ships so that they might transfer the captives to the Tripoli port.

At times, the Grand Master had to issue a safe conduct certificate to enemy ships so that they might transfer the captives to the Tripoli port.“One such case was when Turgut Reis captured the ship Catharinet and took all her load to Djerba in 1548. Following this unfortunate capture for the Christian side, the Knight Augustino Spagno was sent as an envoy to negotiate redemption of the captives and once prices were fixed, a Muslim ship carrying these captives was to sail to the Order’s port in Tripoli.”

Interestingly, although being amid a Holy War against each other, this flourishing trade saw the collaboration and interaction between Christian and Muslim merchants.

“The capture of slaves did not only translate itself into financial rewards but acted also as a means to strengthen commercial ties between the various ethnic subjects of the cross and the crescent. Both Muslim and Christian merchants exploited this cruel reality and at times, this exploitation was so excessive that appeals were made to the local authorities to annul what plaintiffs described as usurious agreements which desperate souls had been forced to endorse in return for their freedom.”

“The Catholic Church strongly prohibited any compensation on loans, whether being related to business or not. Interest was regarded as usury and was not allowed. Often, this situation created shortages of cash money, especially after the Jewish community was expelled from the Maltese Islands in 1492. Nevertheless, there were numerous ways of circumventing this prohibition, such as through the difference quoted in the rate of exchange which would incorporate an agreed rate of interest or by paying the value in other goods.”

Besides ransom agents, there were also those agents who were summoned in order to make arrangements for the purchase of slaves to be delivered to Malta. Gender, age, ethnicity and price were agreed beforehand to eliminate any possible claims for additional payment.

“Although prices of slaves varied considerably, various studies indicate that the average selling price for a slave during the sixtenth century was in the region of 46 scudi. The acquisition of infidel slaves from Tripoli as a commodity for re-sale was one of the most profitable economic activities through which Malta registered a boom in her commerce.”

The arrival of Napoleon in 1798 abolished slavery in Malta and yet from litigation cases found in the Tribunal proceedings, during the early British Period, it is clear that the island’s association with slavery would not be terminated by a simple legislative enactment.

“And yet, back in the eighteenth century, people had already realized that the raiding system was over and that it was not feasible anymore. A new system based on lawful commerce and trade began to emerge; the Pinto stores being evidence of such change.”

(This article was published in the Family Business Supplement issued with The Times of Malta dated 24 February 2017)

-

Christmas inspiration

Thousands of baby Jesus statues begged for my attention during a visit at Il-Mużew tal-Bambini in Birkirkara. However, I felt mostly intrigued by a particular terracotta figure which looked completely different from the rest. Its face had captivatingly unique features and the rest of the body was very life like. Yet it was only when I met its creator, sculptor Chris Ebejer, that I understood its real value, since that baby Jesus was not just a statue but a singular work of art.

Thousands of baby Jesus statues begged for my attention during a visit at Il-Mużew tal-Bambini in Birkirkara. However, I felt mostly intrigued by a particular terracotta figure which looked completely different from the rest. Its face had captivatingly unique features and the rest of the body was very life like. Yet it was only when I met its creator, sculptor Chris Ebejer, that I understood its real value, since that baby Jesus was not just a statue but a singular work of art.“My baby Jesus creations are not popular statues that are meant for domestic use or simply to act as a representation of the son of God. They have an added value because they are sculptures and not just statues,” explained Chris when I met him at his studio in Mqabba.

“When I do such works, my aim is not only to reproduce the tenderness of a baby but also to relay an artistic style and a distinct message. Such art pieces are not restricted just to the Christmas season but they can be cherished all throughout the year due to their artistic significance.”

An unfinished terracotta sculpture of a toddler Jesus lay waiting on a workbench. I couldn’t help noticing some subtle facial similarities between this work and the other one that I had viewed before. I was curious to know whether a sculptor would have a specific image in mind of how Jesus should be represented.

“Before starting to work on something, an artist needs to have a vision of what he intends to create. One wouldn’t picture the exact image in mind but there would already be an idea of the shape, the composition, and the layout of the figure. Details will not be clear but each artist will subconsciously compose some particular features which are typical of his style.”

“I must say that the facial features of this figure were inspired by those of my nephew. When he was a baby and later on a toddler, I studied closely his facial characteristics in order to explore the difference that exists between such a young face and that of an adult. For example, I observed that a toddler’s forehead is large when compared to the rest of the face, the upper lip is usually protruding, the cheeks are chubby and the neck is fleshy.”

The sculpted figure of Jesus looked quite human and earthly and I wondered whether such work involved a spiritual process as well?

“Whenever I am creating a sculpture, my foremost thought is always art. I am not motivated by any religious intentions and I do not aspire to encourage faith or to have people praying in front of my work. I have to admit that the subject is irrelevant to me.”

Nonetheless, although creativity and originality are always his primary goals, Chris revealed that there is a limit on how much one can move out of the religious figures’ codified facial characteristics which our culture has learnt to decipher and expect.

“No one has any idea how Jesus actually looked like, neither as a baby or a child, nor as an adult. Indeed, both his face and the way in which he is represented have changed considerably along the centuries. The belief that some images such as the Veil of the Veronica and the Shroud of Turin could be historically authentic has influenced very much the present impression of Jesus’s face. Once such images are portrayed over and over again and are accepted by society, their characteristics become codified and this will help people to recognize immediately the figure of Jesus. Certainly, as an artist, there are ways and means of how to be creative when dealing with such a significant figure. However, one must know his limits so as not to come out with a profane work.”

In earlier times, when art could reach out to people more than books, especially due to widespread illiteracy, the Catholic Church often used symbols within artistic works to deliver its messages.

“There were various symbols that were portrayed with baby Jesus. In Botticelli’s artwork Madonna of the Pomegranate, Jesus is holding a pomegranate in representation of his suffering and resurrection. On the other hand, in the Madonna of the Carnation by Leonardo da Vinci, Jesus is reaching out to a carnation which is the symbol of Passion.”

Chris pointed out to his sculpture of toddler Jesus where he had also included such symbols.

Chris pointed out to his sculpture of toddler Jesus where he had also included such symbols.“Although in this sculpture, Jesus might look just like any child, there are a number of clues which will hint to the viewer that there is more to it than that. In fact, the child in sitting on a humble box draped in cloth in allusion to when the babies of ancient royal families were placed on thrones. The young figure is holding a miniature cross in his hand and three nails lie down beneath him on the ground. All these objects, together with the boy’s meditative expression as he looks far out beyond his tender age, create an effect which suggests that the child is already seeing his mission for the future.”

As he continues with some final touches on this latest sculpture, Chris reveals that the autumn and wintery seasons tend to inspire him to create new works.

“I am deeply influenced by the change of seasons and by the transformation which they breed in the coloured landscape. Being from the rural village of Qrendi, I am very attracted to nature and my senses are intensely attuned to it. As the leaves start turning orangey red, melting in with the aroma of wet brown soil and the liquorish scent of carobs, I feel stimulated to think about Christmas and the birth and life of Jesus, and it is mainly during this period when I come up with new ideas for works with religious themes. Moreover, the earlier approach of night during these days entices me to stay more indoors and this provides me with much more time to work.”

A look at some of his finished works that were in his studio indicated that this sculptor had a particular preference to terracotta.

“I do love working with terracotta as besides being a natural medium, it also has a pleasant warm colour. It is also more fluid and softer to handle than other materials and so it allows me to work in greater tranquillity. The fact that terracotta has been in use since ancient times enhances also in me that sublime feeling that by utilising this medium, I am helping to keep this traditional technique alive.”

Apart from baby Jesus sculptures, during this season, Chris tends also to come out with new nativity creations.

“Tenderness and the love for the family are the main messages imbued in these works.”

(This article was published in Christmas Times magazine issued with The Times of Malta dated 8th December 2016)

-

Safety at sea

Although the sea may be perceived as a barrier, in ancient times, when no infrastructure existed on land, it was actually the medium which connected one country to another. Travelling on the sea had its own risks and so eventually the idea of insuring a ship and its cargo developed. Traces of the first arrangements between merchants date back to the Roman Period, starting from contracts of sea loans and evolving through the centuries into more complex marine insurances.

Along their history, the Maltese Islands often formed part of important trade routes and therefore local merchants were soon involved in this sector of underwriting risks. A wealth of information related to this aspect is available in old documents which show the development of insurance that was offered against particular risks on the sea. Nonetheless, till now, the origins and progress of marine insurance in Malta have been given little attention.

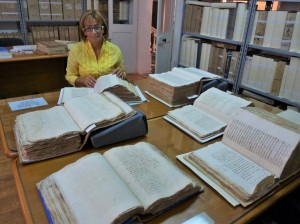

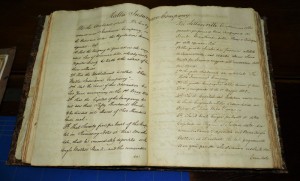

A visit to the Notarial Archives in Valletta where I met historian Dr Joan Abela introduced me to this interesting theme. Always ready to divulge enticing narratives from the valuable sources of these archives, Abela prepared for me a distinguished selection of thick manuscripts in order to help me explore the fine details available within.

A visit to the Notarial Archives in Valletta where I met historian Dr Joan Abela introduced me to this interesting theme. Always ready to divulge enticing narratives from the valuable sources of these archives, Abela prepared for me a distinguished selection of thick manuscripts in order to help me explore the fine details available within.“In antiquity, before marine insurance originated, a sea loan was the only means of transferring risks in maritime transport from the shipper to another person. This consisted of two partners, a traveling and a sedentary one, who pooled their capital in order to invest and share the risk together. With such an agreement, the travelling partner would have more money in hand to work with, whereas the sedentary one would be able to make a profit while staying on land to continue with his work and at the same time avoid the perils that existed out at sea,” explained Abela.

By the Late Middle Ages, as Italian merchants, particularly from Genoa, continued to experiment on these issues of securing vessels and their cargo, marine insurance gradually began to replace this type of agreement.

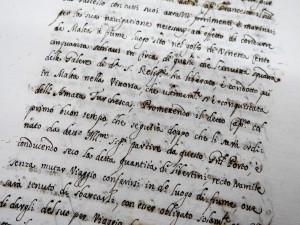

“Since marine insurance was still in its early stages of development, contracts did not adopt a uniform pattern, but varied considerably according to the exigencies of the contractors. Insurance contracts were usually categorized as Securitas by the notary, and were generally divided into two parts.”

“Since marine insurance was still in its early stages of development, contracts did not adopt a uniform pattern, but varied considerably according to the exigencies of the contractors. Insurance contracts were usually categorized as Securitas by the notary, and were generally divided into two parts.”“The first section listed the insurers’ names and the guaranteed premium which was calculated according to the routes, the prevailing conditions along these routes, the type of cargo, and also the type of ship being used. It also covered the kind of information which was regarded as essential for such a contract, that is, the name of the persons insured, specific details regarding the ship which was to undertake the venture, and other specifications regarding the merchandise and its destination. The second part of the contract usually listed the obligations of the insurers, the rights of those insured, and the method of payment.”

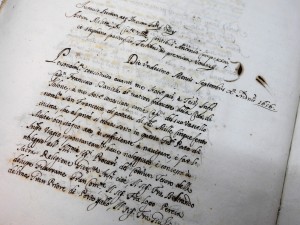

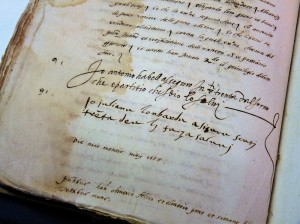

Abela guided me through the Latin elegant black ink scripture which dated to centuries ago. Interestingly, at the beginning of some contracts, prior to the insertion of the usual stereotyped clauses, notaries included an invocation of God’s blessing for a safe trip.

Abela guided me through the Latin elegant black ink scripture which dated to centuries ago. Interestingly, at the beginning of some contracts, prior to the insertion of the usual stereotyped clauses, notaries included an invocation of God’s blessing for a safe trip.‘Al nome De Dio bon viaggio et salvamento Amen’ started a contract dated May 1558.

“Divinity was also cited in other parts of the contracts,” revealed Abela. “In fact, the listing of the perils was often preceded by the phrase che Dio non voglia.”

Abela noted also that although at the time, mariners had a great devotion for the Virgin Mary which is evident from ex-voto paintings, Her name and also the names of saints were not usually mentioned when appealing for such spiritual protection in between legal phrases. This contrasted with the names given to ships that were often named after the Madonna and various saints.

“Indeed these manuscripts can shed light on various subject matters. Amongst the wide data available, one can note the different vessels that were used during the different periods, the names of these ships, the ports to which they travelled, the type of cargo that was carried, and the amount of money which was being insured on it.”

“An insurance contract which was concluded on 4 April 1536 stated that the insurance policy covered a shipment of 18 cantari of spun cotton that was going to be loaded from Birgu and shipped to Licata on the fusta of Giacomo Bonnichi. This fusta was to be captained by Paolo Xuejl or by any other captain appointed in his stead, and was secured to travel to any port which may have been deemed necessary for the purpose of the expedition.”

“An insurance contract which was concluded on 4 April 1536 stated that the insurance policy covered a shipment of 18 cantari of spun cotton that was going to be loaded from Birgu and shipped to Licata on the fusta of Giacomo Bonnichi. This fusta was to be captained by Paolo Xuejl or by any other captain appointed in his stead, and was secured to travel to any port which may have been deemed necessary for the purpose of the expedition.”Interestingly, a clause in the above contract stated that although being insured, the captain was expected to act prudently and to behave as if he was not being offered this protection, in order not to compromise the safety of the merchandise.

“Should any damage or loss occur to the insured goods, the insurers were usually expected to pay the amount insured without any objection within four months from the incident. Yet as we can see from some documents, such as the petition that was put forward by Nob. Giacomo Bonichi against Mag. Pietro Ros and Giovanni Exatopolo in relation to a contract enrolled in the acts of notary Vincenzo Bonaventura de Bonetiis in 1560, the clients were not always satisfied with the way in which claims were met.”

Abela pointed out to a most interesting contract which referred to an insurance of a consigment of apothecary products for the Order’s Infirmary. The list of products acted almost as a showcase of those ingredients which the Hospitallers used in order to produce the required medicine for their patients.

“Those who succeeded to establish themselves in this sector had to have great entrepreneurial skills since this business was still in its infancy and there were lots of risks which one had to deal with. Antonio Habell and Giuliano Lombardo were two of the earliest local entrepreneurs who besides being merchants and traders, they also offered marine insurance services, as may be noted in an insurance contract which they endorsed in respect of the safe consignment of a shipment of timber from Licata in 1558.”

“Those who succeeded to establish themselves in this sector had to have great entrepreneurial skills since this business was still in its infancy and there were lots of risks which one had to deal with. Antonio Habell and Giuliano Lombardo were two of the earliest local entrepreneurs who besides being merchants and traders, they also offered marine insurance services, as may be noted in an insurance contract which they endorsed in respect of the safe consignment of a shipment of timber from Licata in 1558.”Abela lead me to the book Trade and Port Activity in Malta 1750-1800 (2000) by John Debono where one can find detailed research related to aspects of marine insurance.

“As Debono elucidates, marine risks involved were numerous and included: inconsistency in the weather, the questionable conduct of a crew which was generally poorly and irregularly paid and usually comprised men who could not find work ashore, plundering or being taken as a slave by pirates, the unreliability of basic sea charts and portolani which only showed the depth of the water, and the perils that war brought with it.”

This study underlines also that initially, undewriters operated on an individual basis up to circa 1771, and those notaries which succeeded did very well financially. From an examination of insurance policies between September 1754 and August 1755 drawn up by notary Agostino Marchese, who at the time was most renowned with underwriters and insured, reveals that no less than 109 marine underwiters during that period insured a total sum of 686, 385 scudi against marine risks. However, by the 1770s individual undewriters were being replaced by insurance firms and in 1771, we see the establishment of the first insurance company in Malta.

This study underlines also that initially, undewriters operated on an individual basis up to circa 1771, and those notaries which succeeded did very well financially. From an examination of insurance policies between September 1754 and August 1755 drawn up by notary Agostino Marchese, who at the time was most renowned with underwriters and insured, reveals that no less than 109 marine underwiters during that period insured a total sum of 686, 385 scudi against marine risks. However, by the 1770s individual undewriters were being replaced by insurance firms and in 1771, we see the establishment of the first insurance company in Malta.A few years later, the Maltese Islands were in a state of turmoil as they were briefly occupied by the French and this led to a total collapse of the whole local insurance system. A new chapter in this sector initiated with the beginning of the British rule.

(This article was published in the Shipping and Logistics Supplement which was issued with the Times of Malta on 30th March 2016)

-

Take me to church

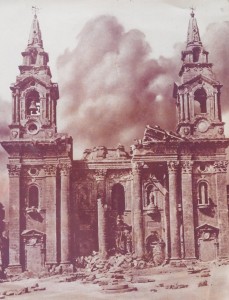

“ ‘They have hit our church!’ cried a man as he stumbled down in the tunnel which was located under the Mall Garden. We were huddling in there for shelter together with many other people as the bombs came down over Floriana,” reminisced Pawlu Piscopo who was eight at the time.

“At this horrible news, my father grabbed me and my brother by the hand and took us out of the tunnel and over to the granaries where a very sad spectacle awaited us. St Publius’ Church had suffered a direct hit. Its dome was gone and the area was surrounded in rubble. Thirteen people who were taking cover in the church’s crypt were killed and eleven more were injured. That was the blackest moment in the history of the parish church of Floriana: April 28, 1942 at 7:50am.”

“At this horrible news, my father grabbed me and my brother by the hand and took us out of the tunnel and over to the granaries where a very sad spectacle awaited us. St Publius’ Church had suffered a direct hit. Its dome was gone and the area was surrounded in rubble. Thirteen people who were taking cover in the church’s crypt were killed and eleven more were injured. That was the blackest moment in the history of the parish church of Floriana: April 28, 1942 at 7:50am.”After their house had been bombed, Pawlu’s family were allowed to take some respite in a large residence which today houses the Floriana Local Council. Yet for four years, they lived mostly underground in this tunnel which probably saved their lives. They took with them only a few belongings and the most cherished items, including a statue of St Publius which dated back to 1928 and used to adorn the model altar that his father had constructed at home.

“Most families in Malta had a model of an altar or a miniature church at home at the time. Unfortunately, many of these had to be abandoned during the war and a good number of them were destroyed when the houses were bombed.”

The craft of church model-making had been introduced to our islands by the Knights of St John back in the 16th century, and therefore its knowledge was a distinct tradition. However the adversity of war ravaged even this precious memory until eventually this craft was almost completely forgotten.

“After the war, people tried to get on with their lives as best as they could. Shops started to open again but those that used to sell miniature items with which to decorate our religious models, dwindled down to almost none. Nevertheless, the passion for model-making was much engrained in our family and when I bought a miniature structure made of four columns and a dome from a man who was leaving Malta to go to live in Australia, my father Carmelo was inspired to use it as the foundation for a model of St Publius’ church,” explained Pawlu.

“After the war, people tried to get on with their lives as best as they could. Shops started to open again but those that used to sell miniature items with which to decorate our religious models, dwindled down to almost none. Nevertheless, the passion for model-making was much engrained in our family and when I bought a miniature structure made of four columns and a dome from a man who was leaving Malta to go to live in Australia, my father Carmelo was inspired to use it as the foundation for a model of St Publius’ church,” explained Pawlu.Carmelo was a very skilled carpenter. He would go from time to time to have a look at the church and then go back to his model and construct an exact copy of the section that he had seen.

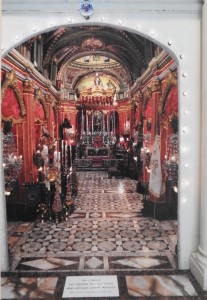

“He used the material which was handy at the time, mostly cardboard, wood and gypsum. I helped him out too in order to build the whole church which included ten altars. Eventually, this model reached a huge size of three by four metres and we could walk in it and look above at the beautiful dome,” Pawlu said proudly.

Once his father grew old, Pawlu continued with the work on this church which they had started back in the early 1960s. As he embellished this model, the wish to set up a group for model-makers in order to share this passion with them, burnt within him.

“On February 26, 1986 which happenned to be the tenth anniversary of my father’s demise, I discussed this idea with two of my friends, Raphael Micallef and Tony Terribile, who were very interested in this sector. We all agreed to do something in order to revive this craft and we sent out adverts in the newspapers to announce the set up of this group which we called Għaqda Dilettanti Mudelli ta’ Knejjes (Church Modelling Society). We were very happy when we received a great response from enthusiastic individuals all over Malta. Soon, a commitee was formed and on March 1986, we organized the first exhibition during the first two weeks of Lent wherein the members displayed the works that they had.”

“On February 26, 1986 which happenned to be the tenth anniversary of my father’s demise, I discussed this idea with two of my friends, Raphael Micallef and Tony Terribile, who were very interested in this sector. We all agreed to do something in order to revive this craft and we sent out adverts in the newspapers to announce the set up of this group which we called Għaqda Dilettanti Mudelli ta’ Knejjes (Church Modelling Society). We were very happy when we received a great response from enthusiastic individuals all over Malta. Soon, a commitee was formed and on March 1986, we organized the first exhibition during the first two weeks of Lent wherein the members displayed the works that they had.”It was certainly a great satisfaction to see this society thrive and grow along the years, always adding up new members of various ages. Today, around 400 members form part of this group which operates from its premises at 37, East Street, Valletta.

“This year we are delighted to celebrate the 30th anniversary from the establishment of this society,” Pawlu said. “The annual exhibition has been taking place each year. Besides offering the opportunity to showcase our members’ works, this event has served to help our members and the public which visits it, to meditate during the Lent period and to prepare for the Easter celebrations.”

“This year we are delighted to celebrate the 30th anniversary from the establishment of this society,” Pawlu said. “The annual exhibition has been taking place each year. Besides offering the opportunity to showcase our members’ works, this event has served to help our members and the public which visits it, to meditate during the Lent period and to prepare for the Easter celebrations.”A bi-monthly magazine, Il-Knisja Tiegħi (My Church), which was also initiated by Pawlu, is marking its 30th anniversary too. Members have been writing features in it related to different aspects of religious folklore, thereby kindling even further interest in model-making.

Once again this year, the society has organized this exhibition which saw the participation of several of its members. Exhibits varied and included small to large statues of the passion of Christ and Easter, statues of Blessed Mary and several saints, models of altars, church facades and whole churches made of different materials.

“I hope that I’ll have enough strength to exhibit my large model of St Publius’ church,” revealed Pawlu at one point. “It takes me four weeks to set it up on a large platform and to connect the miniature chandeliers and light fittings to electricity. I am getting old now and such work is very tiring.”

“I hope that I’ll have enough strength to exhibit my large model of St Publius’ church,” revealed Pawlu at one point. “It takes me four weeks to set it up on a large platform and to connect the miniature chandeliers and light fittings to electricity. I am getting old now and such work is very tiring.”Pawlu has been exhibiting this model in a building besides the Floriana Cathecism Museum for many years now, during the feast of St Publius which takes place two weeks after Easter.

“Many people come to visit my model and they are fascinated with it. Tourists take photos besides it and they ask me how I managed to construct it section by section and yet making it look as a whole. I tell them that there are lifetimes of passion invested within it and that it is imbued with a blend of religious meaning and local traditional skills and creativity.”

At 82 years, Pawlu is serene and thankful to see the society which he has founded together with his friends strengthen itself and adding members to it.

“I just wish that it will continue to flourish for very long,” smiled Pawlu as he looked contentedly around him in order to appreciate the beautiful displayed works of the society’s members.

(This article was published in the Easter Supplement which was issued with The Times of Malta dated 21st March 2016)

-

To die for a piece of bread

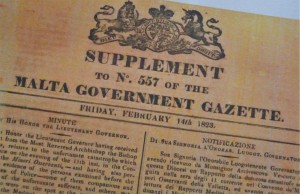

Although Carnival is generally associated with fun, exuberance and colour, it was sadness, tragedy and darkness which marked this festive season on 11th February 1823, after more than a hundred children died in Valletta. Details of this terrible tragedy are immortalized in black and white in the Malta Government Gazette of Friday, 14th February 1823 which is archived at the National Library of Malta in Valletta.

Initially, news of this tragedy was recorded as a Government Notice in the Malta Government Gazette (No. 557) by Richard Plasket, Chief Secretary to Government, wherein he declared that an investigation was taking place in order to obtain any possible evidence regarding this fatal accident. A published report of these findings was later annexed as a Supplement (pp. 3391-2) to the same journal of 14th February 1823.

In this long report, Plasket includes information that was provided to him by the Archbishop of Malta, persons examined before the Magistrates of Police which comprised both relatives of the victims and other individuals who were present during this incident, and also a medical report related to this case.

At the beginning of this statement, he furnishes a context for this mishap wherein he mentions that in those years, during the last days of the Carnival celebrations, it had become a tradition to gather a group of boys aged from 8 to 15, who came from the lower classes of Valletta and the Three Cities, to participate in a particular activity. In this event, children who opted to join were taken in a procession to Floriana or elsewhere, and after attending mass, they received some bread which was financed by the Government and other beneficiaries. The main aim of this activity was to protect the children by keeping them out of the riot and confusion of the Carnival that took place in the streets of these cities. The arrangement of this procession was under the responsibility of the Ecclesiastical Directors who taught Cathecism.

At the beginning of this statement, he furnishes a context for this mishap wherein he mentions that in those years, during the last days of the Carnival celebrations, it had become a tradition to gather a group of boys aged from 8 to 15, who came from the lower classes of Valletta and the Three Cities, to participate in a particular activity. In this event, children who opted to join were taken in a procession to Floriana or elsewhere, and after attending mass, they received some bread which was financed by the Government and other beneficiaries. The main aim of this activity was to protect the children by keeping them out of the riot and confusion of the Carnival that took place in the streets of these cities. The arrangement of this procession was under the responsibility of the Ecclesiastical Directors who taught Cathecism.Indeed, according to this tradition, on the 10th February 1823, some children were taken to attend mass at Floriana and were then accompanied to the Convent of the Minori Osservanti in Valletta (today known as the Convent of the Franciscans of St Mary of Jesus or Ta’ Ġieżu) where they were given bread without any difficulty or trouble. The same ritual was intended to take place the day after. Yet no one had any idea that a series of errors would eventually lead to such a great tragedy.

Everything started according to plan on 11th February 1823. The children were gathered in a group and were taken to mass at Floriana. However, when the ceremony lasted an hour longer than usual, the children’s procession to the Convent in Valletta coincided with the end of the Carnival celebrations, when a great number of jubilant people were returning home. This led to the next blunder, as a number of adults and children who were passing by and who knew of this tradition, secretely mixed in with the other boys in order to share the bread which would be distributed.

Everything started according to plan on 11th February 1823. The children were gathered in a group and were taken to mass at Floriana. However, when the ceremony lasted an hour longer than usual, the children’s procession to the Convent in Valletta coincided with the end of the Carnival celebrations, when a great number of jubilant people were returning home. This led to the next blunder, as a number of adults and children who were passing by and who knew of this tradition, secretely mixed in with the other boys in order to share the bread which would be distributed.In line with the usual arrangement, these boys were to enter into a corridor of the Convent from the door of the vestry of the Church, and were to be let out through the opposite door of the Convent in St Ursula Street, where the bread was to be distributed. In order to prevent the boys who received their share from reentering to take a second helping of bread, it became customary to lock the door of the vestry. Yet this time, since the children were late, this door was left open for a longer time so that they could enter. As the sun was setting and darkness crept in, nobody realized that other men and boys who did not form part of the original group were entering too.

Soon, the boys who were queuing in the corridor found themselves being pushed by these trespassers as they forced themselves in. The situation worsened when eventually the vestry door was closed as usual and the children were shoved further at the end of the corridor where a door stood half open so that no one could get back in a second time.