Posts Tagged ‘Dr Joan Abela’

-

A sea of profits

A search through historical notarial deeds reveals how Maltese businesses exploited the cruel reality of war and slavery, maritime historian Dr Joan Abela tells Fiona Vella.

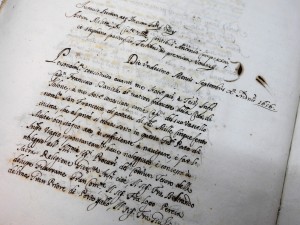

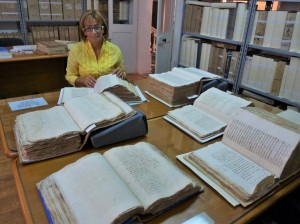

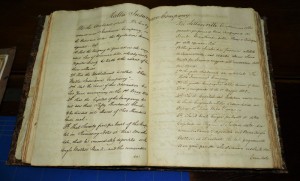

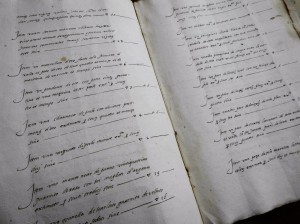

“Even though there are people who might think that the human tragedy which we are experiencing today in the Mediterranean Sea may be something contemporary, in reality, the human element has always been an issue in this region,” Dr Joan Abela says as she refers me to some thick manuscripts that she had set aside at the Notarial Archives in Valletta.

“Even though there are people who might think that the human tragedy which we are experiencing today in the Mediterranean Sea may be something contemporary, in reality, the human element has always been an issue in this region,” Dr Joan Abela says as she refers me to some thick manuscripts that she had set aside at the Notarial Archives in Valletta.We had agreed to discuss the dreadful reality of slavery in the old days and these manuscripts are witness to this phenomenon which took place even in our islands.

“Before the Knights of St John came to Malta in 1530, the Maltese Islands were already involved in the enslavement business and this was quite a legitimate affair at the time. People captured as slaves or captives were considered as commodities and their negotiations were regarded as valuable transactions, which when necessary, were also recorded in notarial deeds.”

Dr Abela continued to inform me that in that era, the traffic of slaves occupied a prime place in the economic activity of maritime trade in the southern Mediterranean since it allowed the profitable exchange of monies and commodities.

“Well aware of the strategic geographical location of Malta in the slave trade business, the Knights of St John established a strong infrastructure in order to attract more merchants and agents. Those who stopped at our islands would have been able to replenish their ships and to make use of the excellent and accomodating financial services which included the availability of notaries, agents, and money changers. Indeed, Braudel stated that Malta together with Livorno acted as a central hub for the slave trade.”

One needed to have a special license to work as a corsair, otherwise he would be regarded as a pirate and could be hanged for capturing ships, cargo or people illegally.

“Since corsairing could render ample returns, people invested in it and received their respective shares from the bounty that the corsairs brought with them after they seized a ship. Investors consisted mainly of businessmen and knights. However, one would also find the Jerosolimitan Nuns of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St John which were located in St Ursula Street, Valletta, forming part of these investors. Their share was due to them for their role in praying for the safe return of the corsairs.”

“Since corsairing could render ample returns, people invested in it and received their respective shares from the bounty that the corsairs brought with them after they seized a ship. Investors consisted mainly of businessmen and knights. However, one would also find the Jerosolimitan Nuns of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St John which were located in St Ursula Street, Valletta, forming part of these investors. Their share was due to them for their role in praying for the safe return of the corsairs.”As Dr Abela began to indicate various episodes from the displayed manuscripts, she admitted that she was often very touched by what she read in those pages.

“Obviously when one looks at history in a collective manner, one would say that there was this particular circumstance taking place during that period and that is it. Yet when one looks into these documents and starts reading a deed about an individual life, one starts empathizing with that person and many questions will come to mind. For example, I came upon a deed wherein a priest was selling a slave together with her son to a Genovese merchant on condition that the latter would baptise the child on that same day. The merchant agreed and the deal was made. When you read something like this, how can you help not wonder who this woman was and from where she had come?”

Corsairing was a high risk job but if all went well, those involved could become rich overnight.

“Men craved for the opportunity to become corsairs and at one point, there were so many men leaving their jobs to join corsair ships that the Maltese Universitas requested the King of Spain to restrain this because the island was at a loss with the local workforce.”

“Not all the captured ships delivered the same profits. A galley of the Sultan which would have been filled with riches and fine cloth, would be precious but not without issues and trouble. Other ships would be carrying worthy cargo such as sugar or wheat. Nonetheless, it was the human cargo which was considered the most profitable.”

Captured people could be sold as slaves or held as captives until they were ransomed.

“The whole process for redemption was very complicated. These contracts unravel all this system including how the involved parties went about to assure the best positive outcome from their deal. An agent would be requested to act as an intermediary between one party and the other, taking responsibility to collect a deposit from the captive and then to take him to an agreed destination in order to collect the rest of the money from his relatives and then release him.”

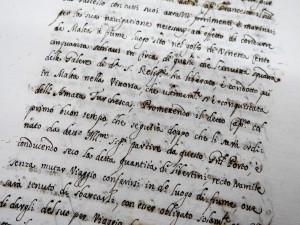

“In April 1558, a slave, Busert Bin Hahmet de Casar concluded the following agreement with his master Giuseppe Baldagno. Busert was transferred to Antonio de Banda from Messina who was a patrone of a ship belonging to Marco Antonio Delixandro, also from Messina. The ship was equipped to undertake a voyage to the Tripolitan fortress of Barbaria. Antonio was to conduct the slave to Tripoli, and from there retrieve 80 gold ducats which was the stipulated price for redemption. This amount was to be remitted either in their value in dinars or in oil, wool or leather goods which the Arabs sold inside the Tripolitan fortress, which goods would be exempt from duty. Busert promised to pay Giuseppe within twenty days of his arrival at the fortress, on condition that the patrone was not to let him disembark unless he received the said payment or its value in goods. Once arrived at destination, the slave would need to make the necessary connection with an intermediary in his own country who would be in a position to acquire the redemption money or goods for him. Once the sum was settled, the slave would become a free man, but if the sum was not paid, he was to return with the same ship and consigned back to his master Giuseppe.”

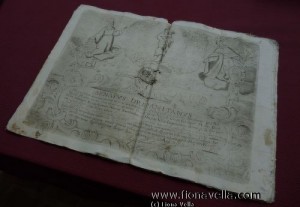

At times, the Grand Master had to issue a safe conduct certificate to enemy ships so that they might transfer the captives to the Tripoli port.

At times, the Grand Master had to issue a safe conduct certificate to enemy ships so that they might transfer the captives to the Tripoli port.“One such case was when Turgut Reis captured the ship Catharinet and took all her load to Djerba in 1548. Following this unfortunate capture for the Christian side, the Knight Augustino Spagno was sent as an envoy to negotiate redemption of the captives and once prices were fixed, a Muslim ship carrying these captives was to sail to the Order’s port in Tripoli.”

Interestingly, although being amid a Holy War against each other, this flourishing trade saw the collaboration and interaction between Christian and Muslim merchants.

“The capture of slaves did not only translate itself into financial rewards but acted also as a means to strengthen commercial ties between the various ethnic subjects of the cross and the crescent. Both Muslim and Christian merchants exploited this cruel reality and at times, this exploitation was so excessive that appeals were made to the local authorities to annul what plaintiffs described as usurious agreements which desperate souls had been forced to endorse in return for their freedom.”

“The Catholic Church strongly prohibited any compensation on loans, whether being related to business or not. Interest was regarded as usury and was not allowed. Often, this situation created shortages of cash money, especially after the Jewish community was expelled from the Maltese Islands in 1492. Nevertheless, there were numerous ways of circumventing this prohibition, such as through the difference quoted in the rate of exchange which would incorporate an agreed rate of interest or by paying the value in other goods.”

Besides ransom agents, there were also those agents who were summoned in order to make arrangements for the purchase of slaves to be delivered to Malta. Gender, age, ethnicity and price were agreed beforehand to eliminate any possible claims for additional payment.

“Although prices of slaves varied considerably, various studies indicate that the average selling price for a slave during the sixtenth century was in the region of 46 scudi. The acquisition of infidel slaves from Tripoli as a commodity for re-sale was one of the most profitable economic activities through which Malta registered a boom in her commerce.”

The arrival of Napoleon in 1798 abolished slavery in Malta and yet from litigation cases found in the Tribunal proceedings, during the early British Period, it is clear that the island’s association with slavery would not be terminated by a simple legislative enactment.

“And yet, back in the eighteenth century, people had already realized that the raiding system was over and that it was not feasible anymore. A new system based on lawful commerce and trade began to emerge; the Pinto stores being evidence of such change.”

(This article was published in the Family Business Supplement issued with The Times of Malta dated 24 February 2017)

-

Safety at sea

Although the sea may be perceived as a barrier, in ancient times, when no infrastructure existed on land, it was actually the medium which connected one country to another. Travelling on the sea had its own risks and so eventually the idea of insuring a ship and its cargo developed. Traces of the first arrangements between merchants date back to the Roman Period, starting from contracts of sea loans and evolving through the centuries into more complex marine insurances.

Along their history, the Maltese Islands often formed part of important trade routes and therefore local merchants were soon involved in this sector of underwriting risks. A wealth of information related to this aspect is available in old documents which show the development of insurance that was offered against particular risks on the sea. Nonetheless, till now, the origins and progress of marine insurance in Malta have been given little attention.

A visit to the Notarial Archives in Valletta where I met historian Dr Joan Abela introduced me to this interesting theme. Always ready to divulge enticing narratives from the valuable sources of these archives, Abela prepared for me a distinguished selection of thick manuscripts in order to help me explore the fine details available within.

A visit to the Notarial Archives in Valletta where I met historian Dr Joan Abela introduced me to this interesting theme. Always ready to divulge enticing narratives from the valuable sources of these archives, Abela prepared for me a distinguished selection of thick manuscripts in order to help me explore the fine details available within.“In antiquity, before marine insurance originated, a sea loan was the only means of transferring risks in maritime transport from the shipper to another person. This consisted of two partners, a traveling and a sedentary one, who pooled their capital in order to invest and share the risk together. With such an agreement, the travelling partner would have more money in hand to work with, whereas the sedentary one would be able to make a profit while staying on land to continue with his work and at the same time avoid the perils that existed out at sea,” explained Abela.

By the Late Middle Ages, as Italian merchants, particularly from Genoa, continued to experiment on these issues of securing vessels and their cargo, marine insurance gradually began to replace this type of agreement.

“Since marine insurance was still in its early stages of development, contracts did not adopt a uniform pattern, but varied considerably according to the exigencies of the contractors. Insurance contracts were usually categorized as Securitas by the notary, and were generally divided into two parts.”

“Since marine insurance was still in its early stages of development, contracts did not adopt a uniform pattern, but varied considerably according to the exigencies of the contractors. Insurance contracts were usually categorized as Securitas by the notary, and were generally divided into two parts.”“The first section listed the insurers’ names and the guaranteed premium which was calculated according to the routes, the prevailing conditions along these routes, the type of cargo, and also the type of ship being used. It also covered the kind of information which was regarded as essential for such a contract, that is, the name of the persons insured, specific details regarding the ship which was to undertake the venture, and other specifications regarding the merchandise and its destination. The second part of the contract usually listed the obligations of the insurers, the rights of those insured, and the method of payment.”

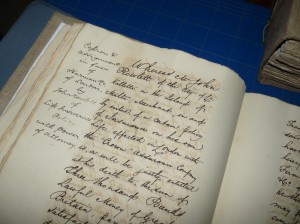

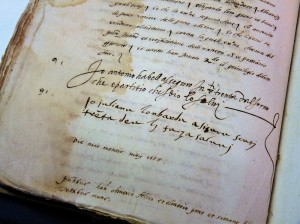

Abela guided me through the Latin elegant black ink scripture which dated to centuries ago. Interestingly, at the beginning of some contracts, prior to the insertion of the usual stereotyped clauses, notaries included an invocation of God’s blessing for a safe trip.

Abela guided me through the Latin elegant black ink scripture which dated to centuries ago. Interestingly, at the beginning of some contracts, prior to the insertion of the usual stereotyped clauses, notaries included an invocation of God’s blessing for a safe trip.‘Al nome De Dio bon viaggio et salvamento Amen’ started a contract dated May 1558.

“Divinity was also cited in other parts of the contracts,” revealed Abela. “In fact, the listing of the perils was often preceded by the phrase che Dio non voglia.”

Abela noted also that although at the time, mariners had a great devotion for the Virgin Mary which is evident from ex-voto paintings, Her name and also the names of saints were not usually mentioned when appealing for such spiritual protection in between legal phrases. This contrasted with the names given to ships that were often named after the Madonna and various saints.

“Indeed these manuscripts can shed light on various subject matters. Amongst the wide data available, one can note the different vessels that were used during the different periods, the names of these ships, the ports to which they travelled, the type of cargo that was carried, and the amount of money which was being insured on it.”

“An insurance contract which was concluded on 4 April 1536 stated that the insurance policy covered a shipment of 18 cantari of spun cotton that was going to be loaded from Birgu and shipped to Licata on the fusta of Giacomo Bonnichi. This fusta was to be captained by Paolo Xuejl or by any other captain appointed in his stead, and was secured to travel to any port which may have been deemed necessary for the purpose of the expedition.”

“An insurance contract which was concluded on 4 April 1536 stated that the insurance policy covered a shipment of 18 cantari of spun cotton that was going to be loaded from Birgu and shipped to Licata on the fusta of Giacomo Bonnichi. This fusta was to be captained by Paolo Xuejl or by any other captain appointed in his stead, and was secured to travel to any port which may have been deemed necessary for the purpose of the expedition.”Interestingly, a clause in the above contract stated that although being insured, the captain was expected to act prudently and to behave as if he was not being offered this protection, in order not to compromise the safety of the merchandise.

“Should any damage or loss occur to the insured goods, the insurers were usually expected to pay the amount insured without any objection within four months from the incident. Yet as we can see from some documents, such as the petition that was put forward by Nob. Giacomo Bonichi against Mag. Pietro Ros and Giovanni Exatopolo in relation to a contract enrolled in the acts of notary Vincenzo Bonaventura de Bonetiis in 1560, the clients were not always satisfied with the way in which claims were met.”

Abela pointed out to a most interesting contract which referred to an insurance of a consigment of apothecary products for the Order’s Infirmary. The list of products acted almost as a showcase of those ingredients which the Hospitallers used in order to produce the required medicine for their patients.

“Those who succeeded to establish themselves in this sector had to have great entrepreneurial skills since this business was still in its infancy and there were lots of risks which one had to deal with. Antonio Habell and Giuliano Lombardo were two of the earliest local entrepreneurs who besides being merchants and traders, they also offered marine insurance services, as may be noted in an insurance contract which they endorsed in respect of the safe consignment of a shipment of timber from Licata in 1558.”

“Those who succeeded to establish themselves in this sector had to have great entrepreneurial skills since this business was still in its infancy and there were lots of risks which one had to deal with. Antonio Habell and Giuliano Lombardo were two of the earliest local entrepreneurs who besides being merchants and traders, they also offered marine insurance services, as may be noted in an insurance contract which they endorsed in respect of the safe consignment of a shipment of timber from Licata in 1558.”Abela lead me to the book Trade and Port Activity in Malta 1750-1800 (2000) by John Debono where one can find detailed research related to aspects of marine insurance.

“As Debono elucidates, marine risks involved were numerous and included: inconsistency in the weather, the questionable conduct of a crew which was generally poorly and irregularly paid and usually comprised men who could not find work ashore, plundering or being taken as a slave by pirates, the unreliability of basic sea charts and portolani which only showed the depth of the water, and the perils that war brought with it.”

This study underlines also that initially, undewriters operated on an individual basis up to circa 1771, and those notaries which succeeded did very well financially. From an examination of insurance policies between September 1754 and August 1755 drawn up by notary Agostino Marchese, who at the time was most renowned with underwriters and insured, reveals that no less than 109 marine underwiters during that period insured a total sum of 686, 385 scudi against marine risks. However, by the 1770s individual undewriters were being replaced by insurance firms and in 1771, we see the establishment of the first insurance company in Malta.

This study underlines also that initially, undewriters operated on an individual basis up to circa 1771, and those notaries which succeeded did very well financially. From an examination of insurance policies between September 1754 and August 1755 drawn up by notary Agostino Marchese, who at the time was most renowned with underwriters and insured, reveals that no less than 109 marine underwiters during that period insured a total sum of 686, 385 scudi against marine risks. However, by the 1770s individual undewriters were being replaced by insurance firms and in 1771, we see the establishment of the first insurance company in Malta.A few years later, the Maltese Islands were in a state of turmoil as they were briefly occupied by the French and this led to a total collapse of the whole local insurance system. A new chapter in this sector initiated with the beginning of the British rule.

(This article was published in the Shipping and Logistics Supplement which was issued with the Times of Malta on 30th March 2016)

-

IN SICKNESS AND IN WEALTH

Although today, many societies relate marriage to two persons falling in love with each other, in the past, matters were quite different. Some of the local marriages, especially in wealthy families, were pre-arranged at age seven, in order to ensure that the children will marry a partner at par or even one which could enhance their title and possessions.

Parents were expected to provide their daughters with a dowry as a form of marriage payment and at times, as a kind of anticipated inheritance. Generally depending on the couples’ status and on the type of marriage contract which they adopted, this dowry could either serve to assist the newly-wed to establish a new household, or else to act as a mode of protection against the possibility of ill treatment to the bride by her husband and his family, since in the latter cases, the dowry might have to be returned back. A dowry offered also an element of financial security in widowhood, particularly if there were little children in the family.

The Notarial Archives in Valletta possess a treasure trove of stories connected to marriages and dowries of the past. Thick manuscripts with remarkably detailed records of people who lived hundreds of years ago, encapsulate these significant moments in the elegant writing in black ink and brings them back to life, each time someone opens the old pages and reads.

“One of the earliest contracts of marriages which one can find at these archives is dated to 1467. In it, Zullus Calleja from Naxxar is listing the objects which he is forwarding to the groom as a dowry in name of his daughter Jacoba. The form of this dowry is alla Maltese, and that means that the future husband will only be able to administer these possessions but not to sell them without his wife’s consent. However, once their children are born, this dowry will automatically be divided into three equal parts; one belonging to the husband, the other to the wife, and the rest to the offspring. Nevertheless, the children will not be able to utilize these belongings until they reach age 15,” revealed historian Dr Joan Abela.

“One of the earliest contracts of marriages which one can find at these archives is dated to 1467. In it, Zullus Calleja from Naxxar is listing the objects which he is forwarding to the groom as a dowry in name of his daughter Jacoba. The form of this dowry is alla Maltese, and that means that the future husband will only be able to administer these possessions but not to sell them without his wife’s consent. However, once their children are born, this dowry will automatically be divided into three equal parts; one belonging to the husband, the other to the wife, and the rest to the offspring. Nevertheless, the children will not be able to utilize these belongings until they reach age 15,” revealed historian Dr Joan Abela.Together with Isabelle Camilleri, a diligent worker at the Notarial Archives, Abela prepared a display of manuscripts pertaining to different eras so that I could analyze the interesting data within.

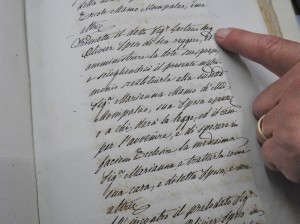

“Whilst I was doing some research about marriage contracts in the old days, I discovered that much of them included also a section marked as dos which related to the dowry being given by the father to the groom. Some of these dowries formed part of the inheritance of the bride and therefore it was declared in the contract that the amount which was being given to her during marriage, would be eventually decreased once she inherits her deceased parents. On the other hand, some contracts stated that this dowry was being donated over and above the future inheritance that the woman will have,” explained Abela.

This study shed light also on different types of dowry contracts which were in existence at the same time during various periods.

“The most popular ones were the contracts that used the alla Greca or the alla Romana custom, which were practically the same thing. Basically, this type of contract stipulated that all the dowry which was forwarded by the bride’s father to the groom could only be administered by the latter but it could never be alienated without his partner’s approval.”

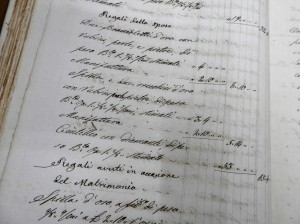

“The most popular ones were the contracts that used the alla Greca or the alla Romana custom, which were practically the same thing. Basically, this type of contract stipulated that all the dowry which was forwarded by the bride’s father to the groom could only be administered by the latter but it could never be alienated without his partner’s approval.”No matter which style was chosen, all these dowry contracts were quite formal and organized. Experts in each sector of the items being included in the dowry were called upon to evaluate these objects professionally, and their names were included in the contract as a guarantee of genuinity. Ultimately, each of these things were described meticulously in the contract, together with their value at the time.

“Each time that I am working on a new manuscript, I am often delighted at the descriptions that I find. They are so rich in detail that I get the impression of seeing or touching the materials being mentioned, or of smelling the scents and perfumes of the objects in question. I find myself literally in another world as I delve through these pages and read the lists of things that this bride carried with her to her new home,” Camilleri said.

Dowries of affluent people could be quite impressive. One of these which was in the alla Romana style, had a list of more than 60 objects and was dated to 1557.

Dowries of affluent people could be quite impressive. One of these which was in the alla Romana style, had a list of more than 60 objects and was dated to 1557.“There is so much to ponder in this contract,” remarked Abela. “The one who was making the dowry was the renowned knight Marshall Fra Guglielmo Couppier who took part in the Great Siege of Malta in 1565. Interestingly, Victoria, the bride, had been Couppier’s slave but he had given her freedom. Moreover, in this contract, he was also forwarding a substantial dowry in her name, worth of a highly noble woman, to her future husband Hieronomu Debonè who worked as a bombardier and blacksmith.”

Victoria’s dowry included a 20 year old black male slave and a 59 year old female slave, refined jewelry made of gold, precious stones and pearls, clothes made from the most costly materials such as silk, velvet and wool, and mattresses, pillows, bedsheets and blankets of the finest luxury.

“Another type of dowry contract that was available was known as alla Latina. I didn’t find many of these and I noticed that generally they were used by peasants or families who were not so well-off. In fact, the main aim of such contracts was to help the couple initiate a new life together, since otherwise, this would have been difficult. The agreement in such contracts stated that after a year from their wedding, whatever the couple owned, including the dowry which the bride had brought with her, would belong to both of them. And once children were born, these possessions would be divided into three equal parts between the husband, wife and offsprings.”

Unlike the other types of dowry contracts wherein the husband was bound to return all the dowry objects to his wife’s father, in the same good state, or even better, should their marriage fail for any reason or if the woman died before having any children, the couple which chose the alla Latina contract shared both the good and bad times together.

Camilleri led me to another manuscript which dated to the 1860 wherein she showed me a long contract that incorporated an inventory of the dowry of a woman who had died and left three small children behind. Her husband was going to get married a second time and so it was required to specify exactly the origin and value of the deceased wife’s possessions.

Camilleri led me to another manuscript which dated to the 1860 wherein she showed me a long contract that incorporated an inventory of the dowry of a woman who had died and left three small children behind. Her husband was going to get married a second time and so it was required to specify exactly the origin and value of the deceased wife’s possessions.“This dowry included also the gifts which she was given during her wedding,” highlighted Camilleri. “Jewelery made the best part of it and it comprised items made of gold, precious stones, pearls and diamonds. Who gives these gifts in weddings nowadays?”

Up to some years ago in Malta, dowries were still handed over to the newly married couple. Most of these couples were provided with practical items which would be useful in their new home, although some admit that they were given so many things that it was hardly possible to use all of them. In fact, a number of them were still lying in cupboards, brand new.

Although one might still encounter a few Maltese couples from the younger generation whose families are adamant to keep this custom alive, the tradition of providing a dowry of goods is certainly dying out. Yet I tend to believe that the dowry itself has not become obsolete but has merely changed form, possibly into money which could be used by the couple to buy a property or to finance their wedding reception.

(This article was published in the Weddings Supplement issued with The Times of Malta of November 4, 2015)

-

Law of the sea

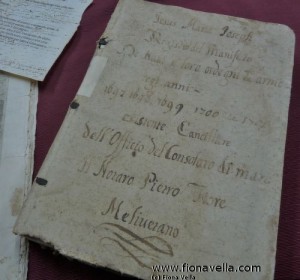

Amongst its various significant documents, the National Archives of Malta house the records of the Consolato del Mare di Malta within the premises of the Banca Giuratale in Mdina. This collection holds the first records of Malta’s own maritime tribunal and sheds light over more than 100 years of maritime laws that were effected between the late 17th century and the early 19th century.

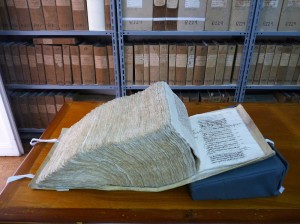

Consisting of a total of 473 items, the documentation of the Consolato del Mare di Malta is presently found in a stable condition. However it requires attention since present storage conditions do not guarantee its future preservation. While, highlighting the huge importance which this collection has to the better understanding of both local and international sea law, maritime historian, Dr Joan Abela, recently appealed for the preservation of this collection for posterity. Following this appeal, a group of individuals who are connected to the Maltese maritime industry, have joined forces in order to come up with an initiative to collect the required funds for this project.

Consisting of a total of 473 items, the documentation of the Consolato del Mare di Malta is presently found in a stable condition. However it requires attention since present storage conditions do not guarantee its future preservation. While, highlighting the huge importance which this collection has to the better understanding of both local and international sea law, maritime historian, Dr Joan Abela, recently appealed for the preservation of this collection for posterity. Following this appeal, a group of individuals who are connected to the Maltese maritime industry, have joined forces in order to come up with an initiative to collect the required funds for this project.“The proper preservation of our archives is always our main focus,” said national archivist and National Archives CEO, Charles Farrugia. “After consulting with our conservators, it was concluded that using the current resources, it would take us about 80 weeks in order to complete the first phase of preservation on the documents of the Consolato del Mare di Malta, and it would cost approximately €25,000.”

This initial work will involve the removal of acidic wrappers from the bundles of documents, cleaning of the bundles, the provision of new conservation grade covers and a condition assessment. Moreover, this collection will be stored in archival quality boxes that will serve for better protection and storage.

Archivist Noel D’Anastas commended the idea of this project, “At the moment, we have 52 metres of shelving dedicated to the collection of the Consolato del Mare di Malta. Although a good part of these documents are in a good condition, some of the bundles require urgent attention and it would be great if they could be preserved as soon as possible, particularly since this material is very much in demand by researchers.”

Archivist Noel D’Anastas commended the idea of this project, “At the moment, we have 52 metres of shelving dedicated to the collection of the Consolato del Mare di Malta. Although a good part of these documents are in a good condition, some of the bundles require urgent attention and it would be great if they could be preserved as soon as possible, particularly since this material is very much in demand by researchers.”The commercial court of the Consolato del Mare di Malta was established in 1697 and its main aim was to coordinate local maritime affairs and to tackle disputes and litigations in a more efficient way so as to facilitate trade. This arrangement was further enhanced by the appointment of experienced merchants in maritime trade in the positions of consuls for the tribunal of the Consolato.

“During the period of the Order of St John, corsairing became one of the major commercial activities of our islands. However, by the end of the 17th century, the politico-economic atmosphere of Malta had evolved into stronger commercial enterprises, thereby lessening the importance of the corso,” explained maritime historian Dr Joan Abela.

“Between the years 1721 to 1723, the corso employed around 700 men whereas circa 3000 men were engaged with the merchant fleet. Therefore the need for a new regulatory system must be observed in this wider context of change from a crusading order to a trading order.”

Till then, Maltese shipping had been administered by the Consolato del Mare laws of Messina and Barcelona. Yet this development created the requirement of a legal framework with which merchants and seafarers could be guided in their dealings with other traders and sellers.

Till then, Maltese shipping had been administered by the Consolato del Mare laws of Messina and Barcelona. Yet this development created the requirement of a legal framework with which merchants and seafarers could be guided in their dealings with other traders and sellers.In order to cater for this demand, Grand Master Ramon Perellos y Roccaful entrusted Fra Gaspare Carneiro with the task of studying the set up of the Consolato del Mare of various countries and particularly those which were used in Messina, Barcellona and Valencia. Thereafter, Carneiro was expected to compile and formulate the regulations for a Maltese Consolato law.

“From the documents that are held today, we can see that this maritime tribunal functioned for many years. In fact, this form of regulation continued to serve this sector until 1814; when the British eventually replaced it with the Corte di Commercio,” elaborated D’Anastas.

Asked about the relevance of this collection today, all three agreed that the study of such documents could enable researchers to understand the evolution of our local commercial trade within the broader Mediterranean context.

“Since law and custom were highly connected, such documentation could also reveal a number of local maritime customs. Furthermore, such a collection could divulge interesting details regarding the economic and social aspect of past societies, and how law and business functioned.” suggested Dr Abela.

“Indeed this collection of the Consolato del Mare di Malta provides a snapshot of various business practices such as the chartering of vessels, the wages of sailors, contracts of commenda or trade agreements made by captains, sailors or merchants, cases involving insurance, freight and trade networks, navigation techniques and many more valuable information. Therefore, its relevance for research applies to different areas of study,” remarked D’Anastas.

Once again, they all agreed about the benefit of preserving such documents which highlight how a particular system has succeeded to continue functioning and elaborating itself over such a long period of time.

Once again, they all agreed about the benefit of preserving such documents which highlight how a particular system has succeeded to continue functioning and elaborating itself over such a long period of time.“History is the foundation on which to build one’s present and future. A country which does not take adequate care of its archives tends to suffer from a sort of forgetfulness,” insisted Dr Abela. “I believe that such a collection should be regarded as a treasure of worldwide significance since its records can explain in detail how people from various countries managed to operate a system with which to work together like clockwork.”

“There is no boundary to how much one can expand in the research of such documentation,” concluded Mr Farrugia. “Likewise, there is no limit to the sort of preservation and conservation that one can apply to such a collection in order to protect it and make it available to future generations. Hopefully, one day, we will be able to digitalize this information so that this masterpiece of knowledge could be more easily shared on a wider scale.”

Sponsors who would like to donate funds for this venture are requested to contact jes@sullivanshipping.com.mt, bsultanasully@gmail.com, apmamo@gasanmamo.com, rpmiller@tugmalta.com, or call 2229 6165.

(This article was published in the Shipping and Logistics Supplement in The Times of Malta dated 18 March 2015)

-

600 sena ta’ memorja pubblika

Xi mkien trid tieqaf! Infatti, għalkemm konxja li hemm ħafna aktar ġabriet interessanti x’nikteb dwarhom, dan ser ikun l-aħħar artiklu tiegħi f’din is-sensiela. Kull artiklu li ktibt kellu l-għan li jeħodna matul vjaġġ ta’ esplorazzjoni tal-kultura u tal-istorja tagħna. Flimkien skoprejna kif primarjament l-iskop maġġuri ta’ dawn il-ġabriet tat-tifkiriet huwa li permezz tagħhom il-bniedem joħloq mezz kif jippreserva l-memorja tal-persuni, tal-perjodi, tal-mumenti u tal-affarijiet li l-aktar li jgħożż u li ma jrid qatt li jintilfu jew jintesew. Għalkemm uħud fostna jaħsbu li l-memorja hija xi ħaġa li żżommok imwaħħal mal-passat, fir-realtà din għandha l-potenzjal li tgħaqqad l-għeruq tal-bniedem modern ma’ dawk tal-antenati tiegħu u b’hekk tirrinforza l-pedament tal-umanità ta’ llum. Permezz tal-memorja, tarbija li titwieled fid-dinja ma jkollhiex għalfejn tibda kollox mill-bidu, u wara li titgħallem dak li sar qabel, hija tista’ tkompli tibni fuq dak li sabet u b’hekk tinfetaħ l-opportunità għall-progress.

Din il-ġimgħa ddeċidejt li niddedika l-aħħar artiklu tiegħi lill-Arkivju Notarili li sfortunatament għamel żmien twil abbandunat. Infatti min jaf kemm il-darba għaddejt minn quddiem din il-binja antika li tinsab fi Triq San Kristofru, kantuniera ma’ Triq San Pawl fil-belt Valletta, bla qatt bsart x’seta’ kien hemm wara dak il-bieb kbir. Fi żjara li għamilt f’dan il-post, tkellimt ma’ l-istorika, Dr Joan Abela, u mar-restawratriċi tal-karta u l-kotba, Dr Theresa Zammit Lupi, dwar il-ġabra ta’ aktar minn għoxrin elf reġistru ta’ kitbiet notarili li jinsabu f’dan l-arkivju u li wħud minnhom imorru lura saħansitra sas-seklu 15. Stennejt li kont ser nisma’ elf ġrajja dwar dawn id-dokumenti imma żgur li m’għaddilhiex minn rasi li kont ser nara b’għajnejja t-tifrik tal-ġebel ta’ żmien it-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija li jinqala’ minn bejn il-paġni tagħhom waqt it-tindif tagħhom!

Oriġinarjament, l-Arkivji Notarili twaqqfu fl-1640 mill-Gran Mastru Lascaris u kienu jinsabu fl-Oratorju ta’ San Ġwann. Wieħed mill-għanijiet tagħhom kien li jiġbru fihom il-volumi ta’ dawk in-nutara li ma kienux għadhom jipprattikaw jew li kienu mejta, sabiex iservu bħala sors ta’ referenza. Fatt kurjuż huwa li f’dan il-perjodu, kull min ried jilħaq nutar kellu jmur jistudja barra minn Malta, ġeneralment f’Palermo. Barra minn hekk, il-liċenzja biex nutar jibda jipprattika u l-inħawi fejn dan seta’ jaħdem, kienu jiġu deċiżi mill-Gran Mastru.

Fuq mejda ppreparata apposta għalija, ħalli nkun nista’ napprezza dak li joffri dan l-arkivju, sibt numru ta’ manuskritti mill-ifjen jistednuni biex nagħti titwila lejn il-memorja li tħalliet maħżuża fuq il-paġni antiki tagħhom. Minbarra l-kitba raffinata tipika ta’ dak iż-żmien, stajt nosserva wkoll id-dekorazzjonijiet li bihom ġew imżejjna dawn il-volumi. Skoprejt ukoll illi dawn il-volumi rnexxielhom jirbħu t-theddida taż-żmien għal daqs tant snin minħabba li l-paġni tagħhom inħadmu mid-drapp u għalhekk huma aktar reżistenti mill-karta li nafu llum. Dettal ieħor interessanti huwa illi l-materjal li ntuża biex jgħatti u jipproteġi l-qoxra ta’ numru minn dawn il-manuskritti, fir-realtà huwa aktar antik u prestiġġjuż mill-volum innifsu! Żewġ eżempji li rajt kienu jinvolvu dokument ta’ prova ta’ nobbiltà ta’ żmien il-Kavallieri, u faċċata ddiżinjata bin-noti sbieħ u kkuluriti tal-kotba tal-kant korali li nħolqu fil-perjodu tal-Gran Mastru l’Isle Adam fis-16 il-seklu, liema kotba llum jinsabu fil-Kattidral ta’ San Ġwann. Biex nifhmu ġest bħal dan, irridu niftakru li meta dawn il-paġni tqaċċtu minn dawn il-kotba prezzjużi biex jiġu riċiklati bħala għata għall-volumi oħra, dan il-materjal kien qed jiġi mitqies bħala antik u żejjed.

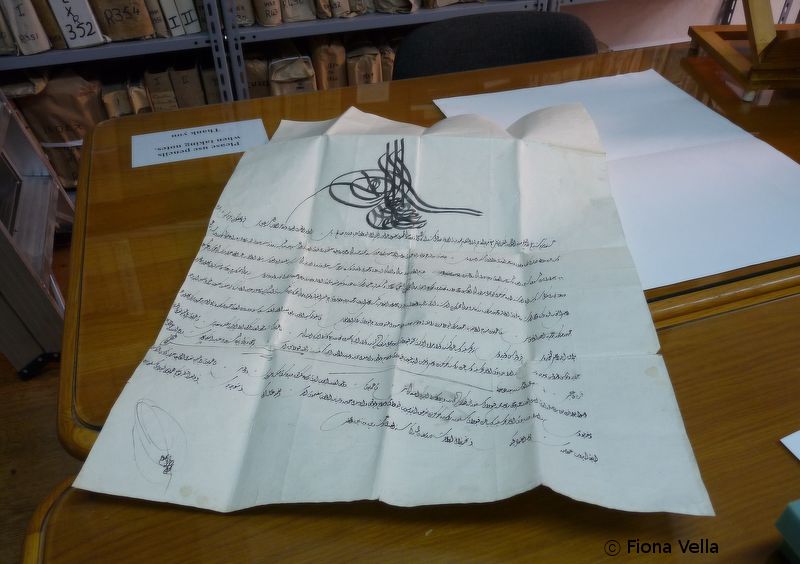

Dokument ieħor li rajt, kien juri l-ewwel forma ta’ passaport miktub fuq karta enormi. Dan il-passaport partikolari kien inħareġ minn Sultan Ottoman sabiex jagħti l-permess uffiċċjali lil kaptan Nisrani sabiex dan ikun jista’ jivvjaġġa bil-bastiment tiegħu f’territorju Mislem, mingħajr ma jiġi aggredit u mingħajr ma ssirlu ħsara fil-merkanzija li jkun qed iġorr. Dan kien żmien meta kursara nsara u misilmin kienu sikwit jattakkaw il-bastimenti li jkunu fuq il-baħar ħalli jisirqulhom il-merkanzija u jieħdu n-nies li jsibu fuqhom bħala skjavi. Infatti, dokument ieħor kien jinvolvi l-kuntratt ta’ assikurazzjoni li tħallset minn kaptan ta’ bastiment fl-1536 ħalli jassikura l-merkanzija tal-qoton li kien ser jitrasporta.

Min-naħa l-oħra, manuskritt ieħor kellu miktub fid-dettall il-kundizzjonijiet maqbula fuq negozju ta’ skjava, fejn fl-1535, persuna li ġġib l-isem ta’ Intlohef, li kienet Musulmana minn Tuneż, kienet qed tiġi mibjugħa lil wieħed Malti għall-prezz ta’ 40 skud. Did-darba, fil-ħażż ta’ din il-kitba, wieħed jista’ josserva l-perċezzjoni tad-drittijiet tal-bniedem, li kienu għal kollox differenti minn ta’ llum. Fil-fatt, dawn l-imsejkna li kienu jinqabdu bħala skjavi, spiss kienu jiġu trattati bl-istess mod kif kienu jitqiesu l-annimali jew xi prorpjetà oħra. Dan l-element huwa ċar fl-użu tal-lingwaġġ li jirreferi għalihom fejn ngħidu aħna l-iskjavi mibjugħa fi Tripli kienu jissejħu ‘testa di nigri’, oħrajn jirreferu għall-grupp ta’ skjavi bħala ‘a cargo of slaves’, filwaqt li kien hemm terminu speċifiku użat fil-bejgħ tagħhom li kien jgħid li dawn qed jinbiegħu ‘pro uno sacco ossibus pleno’, jiġifieri bħala xkora għadam. Din tal-aħħar tfisser l-istess bħat-terminu ta’ llum ‘tale quale’ u allura min jixtri skjav, ma setax imur lura għand il-bejjiegħ u jitlob il-flus lura jekk dan jimrad jew imutlu. Sadanittant, permezz ta’ dokumenti oħra, wieħed jista’ jifhem ukoll x’tip ta’ nies kienu qed jixtru dawn l-iskjavi. Ngħidu aħna, jekk tivvaluta ċerti dokumenti ta’ l-ewwel snin meta ġew il-Kavallieri fostna u marru joqogħdu l-Birgu, tara li f’daqqa, il-prezz tal-proprjetà ta’ dawk l-inħawi sploda hekk kif ħafna bdew ifittxu biex jixtru dar f’dawn l-inħawi ħalli jkunu aktar viċin ta’ dawn l-individwi nobbli jew inkella għax hemm kien hemm aktar xogħol. Infatti permezz ta’ kuntratt ta’ bejgħ ta’ dar li kellha kamra, kċina, intrata u bir, naraw li din kienet tiswa 40 skud, prattikament daqs kemm kienu qed jinbiegħu l-iskjavi. Għaldaqstant, dan jikkonferma li biex wieħed seta’ jiflaħ il-lussu ta’ skjav, ried ikollu flus mhux ħażin.

Dokument ieħor partikolari mmens kien miktub minn testatur fis-sena 1814 fuq biċċa njama peress li f’dak iż-żmien kienu jaħsbu li l-injam ma setax iġorr mard fuqu. Dan kien żmien il-pesta qalila li kienet laqtet lil Malta fl-1813 u n-nies kienu qed jieħdu l-prekawzjonijiet kollha sabiex ma jxerrdux il-marda. Infatti din il-biċċa njama twasslet lin-nutar li mbagħad kiteb il-kuntratt ġewwa manuskritt. Mur għidlu li fir-realtà l-injam kien kompliċi ma’ din il-marda u li jekk mimsus minn xi ħadd milqut bil-pesta, huwa kien jitrasferixxi l-infezzjoni lill-bniedem li jmissu wara!

Sa minn żmien il-Kavallieri, il-liġi kienet titlob lin-nutara kollha sabiex dawn jiddepożitaw tliet tipi ta’ dokumenti: il-bastardello (li kellu fih il-minuti li kienu jittieħdu waqt li jkunu qed jinkitbu l-atti), id-dokument oriġinali tal-kuntratt, u kopja tiegħu tar-reġistru. Fil-fatt, f’dan l-arkivju wieħed isib eluf ta’ bastardelli u ta’ kopji tar-reġistru, mentri l-kuntratti oriġinali jinsabu fl-arkivju prinċipali tal-Arkivji Notarili li jinsab fi Triq Mikiel Anton Vassalli. Il-bastardelli huma importanti ħafna minħabba li fihom ir-riċerkatur jista’ jsib diversi noti addizzjonali bħal ngħidu aħna noti ta’ kontijiet jew ħlas, xi ħaġa li n-nutar ma setax jagħmel fuq il-kuntratt oriġinali li ma setax jintmess. Il-lingwa użata f’dawn id-dokumenti tvarja minn perjodu għall-ieħor b’riflessjoni tas-soċjetà ta’ dak iż-żmien: sat-18 il-seklu l-lingwa hija primarjament bil-Latin, imbagħad fid-19 il-seklu l-lingwa użata taqleb għall-Ingliż u għat-Taljan, waqt li hu biss fl-20 seklu li nibdew naraw l-użu tal-Malti antik.

Dr Joan Abela insistiet għal aktar minn darba dwar l-importanza ta’ dan il-materjal li jinsab maħżun f’dan l-arkivju, liema materjal ikopri madwar 600 sena ta’ storja kontinwa ta’ diversi livelli tas-soċjetà. Iżda akkost li dil-ħażna tiswa mitqla deheb, din għadha ma ġiet analizzata b’mod xjentifiku u storiku u allura l-potenzjal ta’dan ir-riżors mhux qed jiġi utilizzat. Sfortunatament, dawn l-arkivji għadhom mhumiex meqjusa bħala patrimonju minħabba li għall-istat huma jidhru bħala dokumenti legali. Infatti huma jaqgħu taħt ir-responsabbiltà tan-Nutar Prinċipali tal-Gvern u mhux tal-Arkivista Nazzjonali.

Diffikultà oħra hija li ħafna minn dawn il-manuskritti jinsabu f’qagħda mwiegħra peress li huma kienu nġabru minn taħt it-tifrik minn post fi Strada Stretta fejn kienu merfugħa, wara li dan intlaqat mill-bombi tat-Tieni Gwerra Dinjija. Jidher li xi ħadd kien tqabbad ineħħi dawn id-dokumenti sabiex jiġu salvati u b’hekk huma nġabru malajr mill-art, tpoġġew f’għadd ta’ kaxxi, inġiebu f’dan il-post fejn qegħdin bħalissa, u tħallew hemm għal snin sħaħ bla ma ħadd qatt misshom. Dr Theresa Zammit Lupi spjegatli kif mhux darba u tnejn li jsibu xi volum letteralment maqsum fin-nofs b’konsegwenza ta’ xi splużjoni waqt il-gwerra, jew xi volumi oħra mtaqqba bis-shrapnel.

Intant, għal dawn l-aħħar 10 snin il-Kunsill għar-Riżorsi tal-Arkivju Notarili li huwa NGO volontarju, ħadem bis-sħiħ biex ilaqqa’ flimkien lir-riċerkaturi, lill-akkademiċi u lil ċittadini oħra bil-għan li dawn jappoġġjaw lin-Nutar Prinċipali tal-Gvern u lill-impjegati ta’ dawn l-arkivji sabiex din il-kollezzjoni tkun ippreservata. Fil-fatt Dr Abela, membru ta’ din l-NGO, ilha taħdem f’dawn l-arkivji għal għaxar snin b’mod volontarju bl-iskop li xi darba hija tara d-dokumenti kollha restawrati, konservati u ikkatalogati sabiex dawn ikunu jistgħu jservu bħala riżors sinifikanti ta’ referenza għar-riċerkaturi. Grazzi għal numru ta’ sponsors li jgħinu finanzjarjament lill-arkivju notarili biex jitkompla dan ix-xogħol, ammont konsiderevoli minn dawn il-manuskritti ġew restawrati u konservati. Infatti, is-sena li għaddiet feġġ raġġ ta’ tama li jitwettaq ħafna aktar xogħol meta l-HSBC għadda donazzjoni ta’ 100,000 ewro lil dan l-arkivju. B’dawn il-fondi l-arkivju seta’ jimpjega żewġ esperti fil-konservazzjoni tal-karta u b’hekk dawn bdew jorganizzaw numru ta’ dokumenti li ilhom mitluqin għal għexieren ta’ snin.

Dr Zammit Lupi spjegatli kif il-proġett li qed taħdem fuqu jikkonsisti fit-tindif u l-organizzazzjoni ta’ kwantità kbira ta’ bastardelli. Għalissa dan il-proġett qiegħed jiffoka biss fuq it-tneħħija ta’ dawn il-frammenti jew volumi, mill-kaxxi li nġabru wara l-gwerra, fejn id-dokumenti ta’ 600 sena qegħdin imħallta ħallata ballata. Wara, dawn id-dokumenti jitnaddfu ħafif b’pinzell biex jitneħħa t-trab, u kultant anki l-ġebel, minn ġo fihom. Imbagħad huma jitqassmu f’folders ‘acid free’ u jintrefgħu f’kaxxi oħra skont in-nutar li ħadem fuqhom u d-dati tagħhom.

Jekk tieqaf tixrob is-sitwazzjoni kollha f’daqqa, żgur li taħbat taqta’ qalbek li xi darba dawn id-dokumenti kollha se jiġu rkuprati. Madanakollu, dawn l-arkivji sikwit jagħmlu sejħa għall-voluntieri li jixtiequ jagħtu daqqa t’id f’dan ix-xogħol, u ftit għajnuna oħra, dejjem tagħmel differenza pożittiva. Infatti waqt din l-intervista, iltqajt ma’ wieħed mill-voluntieri, l-arkivista Ivan Ellul, li fil-preżent qiegħed jieħu ħsieb ifassal indiċi tal-bastardelli sabiex biha tinbena database għar-riċerkaturi. Fost it-8000 bastardello li hemm, tlestew 3000 minnhom u għalhekk fadal ħafna aktar xogħol xi jsir. Huwa stqarr li “hija esperjenza sabiħa wisq li taħdem b’kuntatt dirett ma’ volum ta’ 400 sena. Ċertament, f’pajjiżi oħra, din l-opportunità toħlomha biss tista’.” Voluntiera oħra, Sarah Watkinson, li qed tistudja Masters fl-Istorja u hija wkoll id-Deputat Chairperson tal-HSBC Bank Foundation, hija responsabbli mill-proġett tan-nutara Ingliżi. Dan il-proġett jinvolvi l-qari tad-dokumenti tas-seklu 19, meta n-nutara kienu jużaw il-lingwa Ingliża u Taljana, sabiex imbagħad id-dettalji l-importanti jiddaħħlu f’database li aktar tard se toffri referenza utli ħafna għar-riċerkaturi. Hija qaltli li fl-arkivju notarili “qisu l-Milied kuljum għax spiss issib informazzjoni li tissorprendik!”. Barra minn hekk hija spjegatli li f’dan il-proġett huma għandhom bżonn l-għajnuna ta’ voluntieri li jafu jaqraw u jiktbu b’dawn iż-żewġ lingwi.

Staqsejt x’hemm bżonn biex wieħed jingħaqad magħhom bħala voluntier u rċevejt ir-risposta pronta u diretta “Imħabba lejn l-arkivju!”. Hija din l-imħabba li l-individwi nvoluti hawnhekk jippruvaw jittrażmettu lill-oħrajn bil-ħsieb li ħafna aktar nies japprezzaw li wara dawn il-ħitan storiċi ta’ din il-binja antika, il-poplu Malti jippossjedi teżor. “Hawnhekk hawn il-memorja ta’ mijiet ta’ snin tal-antenati tagħna. Huwa obbligu u dritt tagħna li naħdmu biex nippreservaw dawn id-dokumenti li jagħtuna identità,” sostniet Dr Abela.

Intant, dan l-aħħar inħolqot ukoll Steering Committee għar-Rijabilitazzjoni tal-Arkivji Notarili u din diġà kellha laqgħat mas-Segretarjat Parlamentari Għall-Ġustizzja sabiex tiġi diskussa l-possibilità li dawn l-arkivji jiġu meqjusa bħala parti mill-patrimonju Malti. Barra minn hekk, dan il-grupp qiegħed jaħdem bis-sħiħ biex jivvaluta l-opportunità li ssir applikazzjoni għall-fondi tal-Unjoni Ewropeja ħalli kemm il-binja ta’ dan l-arkivju u kif ukoll id-dokumenti li jinsabu miġbura fih jiġu restawrati u konservati sabiex tingħatalhom funzjoni aktar xierqa. B’hekk kemm ir-riċerkaturi u kull min iżur dan il-post isib ambjent li jilqgħu ferm aktar.

Għal aktar informazzjoni dwar dan l-Arkivju Notarili wieħed jista’ jċempel fuq 21224217 ext 427, inkella jissieħeb fil-paġna tal-Facebook Notarial Archives Preservation – Call for Volunteers.

(Dan l-artiklu ġie ppubblikat fis-sensiela ĠABRIET IT-TIFKIRIET (20 Parti) fit-Torċa tas-16 ta’ Marzu 2014)

Travelogue

Archives

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jan | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

Recent Posts

- A MATTER OF FATE

- MALTA’S PREHISTORIC TREASURES

- THE MAGIC IS IN THE DETAIL

- THE SELLING GAME

- NEVER FORGOTTEN

- Ġrajjiet mhux mitmuma – 35 sena mit-Traġedja tal-Patrol Boat C23

- AN UNEXPECTED VISIT

- THE SISTERS OF THE CRIB

Comments

- Pauline Harkins on Novella – Li kieku stajt!

- admin on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Albert on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Martin Ratcliffe on Love in the time of war

- admin on 24 SENA ILU: IT-TRAĠEDJA TAL-PATROL BOAT C23