Posts Tagged ‘monastery’

-

A life of prayer

The concept of life as a cloistered nun has often intrigued people. How could one choose to deny oneself the privilege of freedom and instead opt for a life locked up in a monastery, when the rest of humanity dreaded even the thought of it?

As I knocked on the heavy door of the Monastery of the Augustinian Cloistered Nuns of St Catherine which is located in Republic Street, Valletta, I wondered how I was going to probe for an answer to this dilemma. Soon, a female voice responded from the intercom and when I identified myself, the door opened automatically and I stepped inside. The sight of three barred windows amid a thick white-washed wall bound me at a standstill and I stood there in silence and awe, unsure of what I was expected to do.

Indeed, I was quite surprised when Rev. Mother Abbess Sr. Michelina Mifsud called me in, for I had believed that this interview would take place behind bars and that I would never have the opportunity to look at her face.

“This would not have been possible if you had come to us about eight years ago,” responded Sr. Michelina as she read the question in my eyes. “At that time, you would have needed a special permit in order to contact us, and on your arrival, I would have sounded a bell so that all the other nuns would know that you’re here and they would retire to their rooms until you left.”

“Necessary communication with people used to take place only behind those bars,” she continued to explain. “We could neither read newspapers, nor hear the radio or watch television. Our lives were meant to be completely shut from the rest of the world so that we could focus only on God and our prayers. None of the nuns could get out of this monastery except when they needed aid for serious health reasons. We could not even visit our parents when they were sick and if they died, we were not allowed to attend their funeral. However, at times, our close family members could come to see us at the monastery and we greeted each other from behind the bars.”

I felt dumbfounded and looked down at the floor, searching for a way to question her how and why, until I could not resist no more and spoke out.

“This style of life does not make us feel miserable because this was our choice,” responded gently Sr. Aloisia Bajada who had joined us silently. “Our faith keeps us strong and prevents us from feeling depressed. Certainly there are moments when life gets pretty hard but whose does not? I am sure that even though you did not choose to become a cloistered nun, you too have to make several sacrifices for your family. So, you see, there is not so much difference between us.”

I watched them closely, trying to sense any strange move or reaction which might reveal a hint of unhappiness but instead I was met with sincere serene demeanour which was almost saintly.

“Sometimes even we find it difficult to understand and explain our vocation,” expanded the nuns. “We tend to regard it as a gift from God.”

We started to walk around the monastery and here I was in for another revelation. For the nuns did not live within some somber building but in a spacious and historical palace which was constructed during the period of the Knights of St John.

“This monastery has a long and interesting history,” told me Sr. Aloisia as she watched me admire the old paintings hanging on the walls, the colourful painted floor tiles and the exquisite architecture. “In my earlier years, it was my joy to delve within this monastery’s ancient archives which go back to 1606. They narrate detailed incidents and engaging stories which took place in this building and in the lives of the nuns that lived here hundreds of years ago. Surely, it is a pity that very few people have ever laid eyes upon them!”

At 88 years, Sr. Aloisia is the oldest of the remaining six nuns in this monastery. I was delighted by her passion towards the history of this place which has been her home for the last 70 years. As she led the way ahead, she informed me that originally this building was the residence of Marquis Giovanni and Katarina Vasco Oliviero, and it was known as Casa Vanilla. In 1576, this couple went through a rough time when their son contracted the plague, and in desperation, Katarina, who was a devotee of St Catherine, pledged to donate her house to the Church if her son survived. The boy did survive and Katarina was adamant to keep her word. However, when in 1611, she got to know of a group of girls known as ‘Orfanelle della Misericordia’ who had decided to become cloistered nuns and were taking care of children with family problems, she decided to give her property to them.

In order to change this palace into a monastery, the couple had to buy some of the neighbouring properties so that they could accommodate about 45 nuns, 15 girls and a chapel. This is why today, this monastery stretches out into Republic Street, St Christopher Street, Strait Street and also a section of St Dominic Street. Incidentally, within a year from their testament this noble couple died and since their son had already died before them, the cloistered nuns of St Catherine inherited all that remained.

By time, it became customary for some of the girls of the nobility to take their vows and join this monastery, and this included Grandmaster Manuel Pinto de Fonseca’s sister. Certainly, these girls brought with them generous dowries which supported a comfortable life. However, in 1714, the monastery required huge structural changes and much of the money ran out. Then, in 1798, when the French occupation took over Malta, the nuns found themselves in a dire state of poverty and they could not afford to take care of children any more. The number of nuns dwindled to eight but once the French left our islands, new nuns joined the monastery and life started afresh.

We entered into a lift which took us straight up to the monastery’s huge roof. A breath-taking view of the splendid architecture of the other Valletta buildings welcomed us and a fresh breeze whirled around us. The nearby wide blue sea was shiny and tempting, and we could see sea-gulls gliding smoothly over its surface.

“How can we feel restricted when we have all this to enjoy?” the two nuns asked me with a bright smile on their faces.

We stood together in silence, relishing the stillness and the beautiful environment which surrounded us. Then, the nuns shared with me what had led them to make this particular choice in life.

“Look down there,” asked me Sr. Aloisia as she indicated far below at the monastery’s garden which originally was the quarry from which the stone for this building was extracted. “During World War II, that garden suffered a direct hit and the nuns went to seek refuge at Ta’ Ċenċ in Gozo. I was 16 and from Xagħra and I did not even know what a cloistered nun was. One day, I saw some creative sewing which they had done and I felt curious to meet them. However, people told me that this was impossible, unless I wanted to join them. I felt terrified at the idea that they could keep me with them and yet finally some older friends accompanied me to see them and I liked the nuns’ company. As time went by, I continued to think about them and when I was 18, I was sure that I wanted to join those nuns who had in the meantime returned to their monastery in Malta. And here I am.”

“I was also 18 when I took my vows and became a cloistered nun of this monastery,” told me Sr. Michelina. “Ironically when I was younger, a priest who often watched me visiting and praying daily in front of St Rita, had suggested to me that I should consider becoming a nun and I was furious! Oh, I want to enjoy life, I told him. The life of a nun is not for me! However, some time later, he convinced me to meet the Rev. Mother Abbess of St Monica who in turn invited me to spend some weekends with them whenever I wanted. Somehow, I liked the idea and little by little I got very close to these nuns until I could not imagine any other life but to stay with them. Then, one day, I went to visit Frenċ tal-Għarb and without even knowing me, he made a cross upon my forehead with some oil that was blessed by the Virgin Mary and he told me that I would soon become a cloistered nun in the Monastery of St Catherine and that eventually I would die there. When I returned home to my father and told him about this, he swore that I would not withstand the life of a cloistered nun for more than 15 days. And yet here I am still after 51 years!”

We went down again and this time I was shown the crypt where all the cloistered nuns of this monastery get buried. Interestingly, in this crypt, one finds also the tomb of the son of the original owners of this building.

From there, we moved on to the small chapel wherein the nuns attend to pray. “After 1963, we received new regulations and many things changed. One of these included the possibility of receiving the public in our monastery, even if we still stand behind bars. Indeed, within these last years, many individuals have sought us for spiritual help and advice. Many more have chosen to join us during mass and so people have grown more accustomed to our presence and I think that their respect towards us has increased, now that they know us better,” told me Sr. Michelina.

“Through these encounters, we want to show people that life does not end when you become a cloistered nun. We simply start a new chapter of a life which is simpler and closer to God. We have our daily chores, we pray and help others, and we also enjoy developing our talents in sewing, crochet and art.”

“We miss absolutely nothing here except the need for more nuns to join us as we are too few now and most of us are also too old,” admitted Sr. Aloisia.

I cherished their warm hug when they embraced me before I left, and for a moment I felt a distinct sense of happinness. Yet once the monastery’s door closed behind me, I was concerned about how these nuns will live, once they will be too old to take care of each other? And what will be this monastery’s destiny if one day these nuns will all fade away?

(This article was published in Focus Valletta Supplement in The Times of Malta dated 1st October 2014)

-

THE NATIVITY IN MINIATURE

When the last month of the year steals its way into our hearts, we find ourselves in a world of light, colours, dreams, hopes and Christmas… and nothing symbolises the

Christmas spirit better than the nativity scene captured in a traditional crib. Fiona Vella went in search of two remarkable examples of this long-standing Maltese tradition.

Christmas spirit better than the nativity scene captured in a traditional crib. Fiona Vella went in search of two remarkable examples of this long-standing Maltese tradition.As December comes round, out come the boxes loaded with colourful accessories and delights which were stored away the previous year: a disassembled Christmas tree, some intricate ornaments and a few old cherished cards.

Yet nothing compares to the allure of a precious crib with its little figurines and the statuette of baby Jesus which needs to be warmed up with Ġulbiena, at least in a country with a strong Christian

tradition like Malta. The annual ritual of setting up the crib is fascinating, but what is this enigmatic fascination which draws us each year to recreate this nativity scene? To unearth this riddle I decided to go back to our roots, seeking out two beautiful antique treasures which lie within our intriguing island.

tradition like Malta. The annual ritual of setting up the crib is fascinating, but what is this enigmatic fascination which draws us each year to recreate this nativity scene? To unearth this riddle I decided to go back to our roots, seeking out two beautiful antique treasures which lie within our intriguing island.MDINA

The first gem is situated deep in the heart of the medieval town of Mdina, shielded in the core of St Peter’s Monastery, the domicile of the Benedictine Cloistered Nuns.

With the aid of Joseph Flask, a diligent writer about the life and history of the Benedictine Monastic Order, I was allowed to meet the Rev. Mother Abbess Sr. Maria Adeodata Testaferrata de Noto OSB who received me warmly and invited me to view the oldest known static crib in Malta.

The monastery itself is a magnificent historic and architectural site, dating back to the 15th century. Nevertheless the experience of stepping inside a location which is customarily prohibited to

outsiders’ eyes took that sense of magnificence one step further.

outsiders’ eyes took that sense of magnificence one step further.Up the stairs and along the innermost corridors, lying dormant behind a wide glass case and heavy curtains was my ‘prize’, and I was overwhelmed with emotion as I beheld this rarely seen fine example of one of the highest Maltese traditions.

No one knows who was its original creator or when it was built, but probably the crib’s first restoration took place in 1826, as the earliest painted signature G.B.G

indicates. A similar unspecified restorer enlarged the crib in 1846 and left a simple mark of G.G. A final revamp dates back to 1977, this time clearly signed by Giuseppe Sammut who painted and added the crib’s scenery.

indicates. A similar unspecified restorer enlarged the crib in 1846 and left a simple mark of G.G. A final revamp dates back to 1977, this time clearly signed by Giuseppe Sammut who painted and added the crib’s scenery.Incredibly, while we were exploring the crib, we chanced upon another signature which Joseph had never noticed before – a coarse reddish scribbling bearing the initials G.G and a not so clear G.I. Evidently the crib seems to hold even more challenges and clues for devotees to decipher.

The crib is embedded with personal memories of several people. In fact, a closer glimpse at its figurines lying around the

unrefined landscape made of glued old sacks and newspapers, reveals that oddly most of the figures do not match each other, either in style, age or even size! This effect was initiated by the nuns themselves when they resolved to bestow the original crib’s population with every relative statuette that came in their possession! Amusingly, more intense exploration discloses even extraneous insertions; such as the Greek classic statuette and an irrelevant building situated at the back. Peculiar as it might seem, this reality exudes a tender feeling as one realizes that the crib actually encompasses the love and memories of each nun that lived with it.

unrefined landscape made of glued old sacks and newspapers, reveals that oddly most of the figures do not match each other, either in style, age or even size! This effect was initiated by the nuns themselves when they resolved to bestow the original crib’s population with every relative statuette that came in their possession! Amusingly, more intense exploration discloses even extraneous insertions; such as the Greek classic statuette and an irrelevant building situated at the back. Peculiar as it might seem, this reality exudes a tender feeling as one realizes that the crib actually encompasses the love and memories of each nun that lived with it.The crib is in fact of somewhat crucial help to the cloistered nuns, helping them to evoke the

meaning behind the holy birth; a tangible item in a life withdrawn from the usual worldly pleasures, which constantly reminds them of the sweet joy of Christmas. Indeed, this very crib inspired the renowned short writings of the Blessed Maria Adeodata Pisani OSB who lived in the monastery for several years. And to this day, the crib continues to instigate the spirits of the other nuns when on Christmas Eve they celebrate a traditional procession which ends up in front of it.

meaning behind the holy birth; a tangible item in a life withdrawn from the usual worldly pleasures, which constantly reminds them of the sweet joy of Christmas. Indeed, this very crib inspired the renowned short writings of the Blessed Maria Adeodata Pisani OSB who lived in the monastery for several years. And to this day, the crib continues to instigate the spirits of the other nuns when on Christmas Eve they celebrate a traditional procession which ends up in front of it.ŻEJTUN

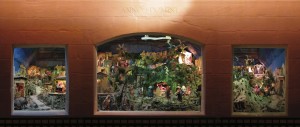

The other route to discovery led me to the quaint village of Żejtun, again to another convent but this time to see the oldest, large, Maltese mechanical crib, which dates back to 1945, a period wherein

our island lay ravaged from the destruction of World War II. It was this devastation that inspired Mons. Emmanuel Galea to create a unique religious symbol as he saw that people desperately needed to rekindle their faith and hope of a better life.

our island lay ravaged from the destruction of World War II. It was this devastation that inspired Mons. Emmanuel Galea to create a unique religious symbol as he saw that people desperately needed to rekindle their faith and hope of a better life.Together with his nephew Pawlu Pavia he devised a plan to build a large mechanical crib which could be motor-driven.

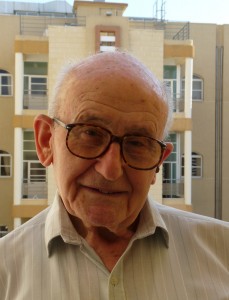

I found Pawlu, now 86, residing in St Vincent De Paule’s residence. Despite his old age, he reconstructed the whole story with sharp clarity and also with a touch of melancholy.

He remembers how some workers were brought in to build a platform made from random pieces of broken doors and windows. Moreover, three openings were cut in one of the room’s wall as the crib

had to represent three sections: what happened before the birth of Jesus Christ, the actual birth itself and what occurred thereafter.

had to represent three sections: what happened before the birth of Jesus Christ, the actual birth itself and what occurred thereafter.The fabrication of papier machè and the layout of the crib he made with the bishop, while he alone was responsible for building the crib’s figurines from wood and iron wire. However the hardest task

was to find some ingenious way of motorizing the figurines’ movements and to actually interelate them at a time when resources were very few. Another difficulty was to surpass the dilemma of an unstable electric current. Incredibly he did all this by means of one single motor which he succeeded to find in a remote shop. Even more incredible is that after 65 years, the crib still functions with this same system!

was to find some ingenious way of motorizing the figurines’ movements and to actually interelate them at a time when resources were very few. Another difficulty was to surpass the dilemma of an unstable electric current. Incredibly he did all this by means of one single motor which he succeeded to find in a remote shop. Even more incredible is that after 65 years, the crib still functions with this same system!This journey also led me to Sister Pawlina Gauci, now 78, who, together with the late Sr. Angela, had the responsibility of dressing the figures. Her three years

missionary work in Persia (now Iran) aided her with good knowledge of the type of material to be used and one by one the figures were clothed with several samples of fabric which a number of shops had contributed.

missionary work in Persia (now Iran) aided her with good knowledge of the type of material to be used and one by one the figures were clothed with several samples of fabric which a number of shops had contributed.Both Pawlu and Sr. Pawlina recall the commotion that this crib raised when it was opened to the public for the first time during Christmas of 1947. Visitors came from all over Malta and there was such a big crowd that the police had to intervene to keep control of the situation!

Now that Pawlu is retired, the crib passed into the care of his nephew Joseph Pavia,

whose great dedication to it is no lesser than his uncle’s. In fact during the last years Joseph renovated the visitors’ room and included a very interesting documentary which recounts the whole story of this crib in five different languages.

whose great dedication to it is no lesser than his uncle’s. In fact during the last years Joseph renovated the visitors’ room and included a very interesting documentary which recounts the whole story of this crib in five different languages.Remarkably, even this crib seems to bear the destiny to be associated with holiness as currently there is the process of the cause for canonization of its instigator, Mons. Emmanuel Galea.

As I left the crib, I pondered about the dedication and devotion behind their creation. The endeavour, the ritual, the almost childish happiness to share a crib with others… all lead to an ancient dream

which St Francis of Assisi had foreseen a long time ago in the village of Greccio. For through its modesty, a crib reminds us that the spirit of Christmas is simple and that it is meant to reach out to our hearts and souls and bathe them in the joy of the birth of Jesus.

which St Francis of Assisi had foreseen a long time ago in the village of Greccio. For through its modesty, a crib reminds us that the spirit of Christmas is simple and that it is meant to reach out to our hearts and souls and bathe them in the joy of the birth of Jesus.(This article was published in FIRST magazine, Issue December 2010. FIRST magazine is delivered with The Malta Independent on Sunday)

Travelogue

Archives

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jan | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

Recent Posts

- A MATTER OF FATE

- MALTA’S PREHISTORIC TREASURES

- THE MAGIC IS IN THE DETAIL

- THE SELLING GAME

- NEVER FORGOTTEN

- Ġrajjiet mhux mitmuma – 35 sena mit-Traġedja tal-Patrol Boat C23

- AN UNEXPECTED VISIT

- THE SISTERS OF THE CRIB

Comments

- Pauline Harkins on Novella – Li kieku stajt!

- admin on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Albert on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Martin Ratcliffe on Love in the time of war

- admin on 24 SENA ILU: IT-TRAĠEDJA TAL-PATROL BOAT C23