Posts Tagged ‘World War II’

-

LIGHTS OUT FOR CHRISTMAS

Christmas time and the days preceding it are generally associated with colour, light, optimism and fun. Yet this was not the case in 1939 when the Christmas season became synonymous with gloom, darkness, uncertainty and fear.

On 18 September 1939, a table showing the duration of the ‘Official Night’ was published in Government Notice No. 459 in The Malta Government Gazette. This table included each day of each month and the beginning and end of what was to be considered as the official night hours. Such instructions formed part of the Malta Defence Regulations, 1939, which aimed to protect the Maltese Islands and its inhabitants as World War II ravaged in other countries.

Two days later, on 20 September 1939, Government Notice No. 473 issued the Lights Restriction Order which was effective from that day. The directions of this Order had to be observed between midnight and 4:30am on every day of the week, and also between 10:00pm and midnight on Fridays. During these times, all lights in any building had to be masked to be invisible from the sea and from the air. No lights, other than lights authorised by the competent authority, were permitted in any open spaces whether private or public, in yards, roofs or open verandas. The use of illuminated lettering or signs in any shops were prohibited unless authorised by the Commissioner of Police or the competent authority. The traffic of motor vehicles during these hours was banned and any vehicles which did not comply with these provisions could be stopped and detained until 6:00am. Obviously, all fireworks were also prohibited.

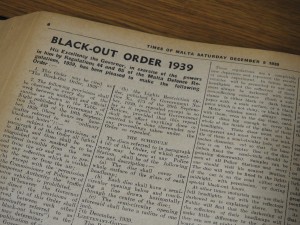

Two days later, on 20 September 1939, Government Notice No. 473 issued the Lights Restriction Order which was effective from that day. The directions of this Order had to be observed between midnight and 4:30am on every day of the week, and also between 10:00pm and midnight on Fridays. During these times, all lights in any building had to be masked to be invisible from the sea and from the air. No lights, other than lights authorised by the competent authority, were permitted in any open spaces whether private or public, in yards, roofs or open verandas. The use of illuminated lettering or signs in any shops were prohibited unless authorised by the Commissioner of Police or the competent authority. The traffic of motor vehicles during these hours was banned and any vehicles which did not comply with these provisions could be stopped and detained until 6:00am. Obviously, all fireworks were also prohibited. An Air-Raid Precautions Order was communicated in Government Notice No. 504 on 4 October 1939. Eventually on 9 December 1939, The Times of Malta published the provisions of The Black-Out Order, 1939, which had to be observed on every day of the week between midnight and the official sunrise. During these hours, all the lights on the Islands had to be extinguished or masked as to be rendered invisible from the sea and from the air. Special Black-Out hours could also be determined when necessary.

An Air-Raid Precautions Order was communicated in Government Notice No. 504 on 4 October 1939. Eventually on 9 December 1939, The Times of Malta published the provisions of The Black-Out Order, 1939, which had to be observed on every day of the week between midnight and the official sunrise. During these hours, all the lights on the Islands had to be extinguished or masked as to be rendered invisible from the sea and from the air. Special Black-Out hours could also be determined when necessary. As part of the Black-Out Order, from 14 December 1939, all motor vehicles which had to travel at night, other than those belonging to His Majesty’s service, had to have their bulbs removed from their lamps. Opaque cardboard discs were to be fixed to the lights of the vehicles and the reflectors’ surface had to be covered with a non-reflecting substance. A white disc had to be affixed at the back of all motor vehicles at a height of three feet from the ground to make them visible on the roads. Traffic of motor vehicles during the black-out was prohibited except for those who obtained permission from the Commissioner of Police or a competent authority.

Another notice which appeared on The Times of Malta of the 9 December 1939 urged the inhabitants to comply with these regulations for their own safety. People were recommended to stay at home and to avoid going out in the darkness. Those who needed to get out were advised to walk on the right-hand side of the road to face oncoming traffic and to carry with them a white object to make them more visible to drivers. Owners of goats were informed to keep their animals off the road at night. On the other hand, drivers were cautioned to drive very slowly and with great care.

Measures were being taken to prepare the people how to take the necessary precautions in preparation of an expected war. Black-outs intended to prevent crews of enemy aircraft from being able to identify their targets by sight. Nonetheless, these precautionary provisions proved to be one of the more unpleasant aspects of war, disrupting many civilian activities and causing widespread grumbling and lower morale.

The Times of Malta of 13 December 1939 reports that some misapprehension had arisen among that section of the public who had to rise early for work and travel by early buses, since it was not clear at what time the bus service started. Indeed, all buses were to continue their usual service provided that they adhered to the regulations regarding headlights and lights, including the inside of the vehicles which had to remain in darkness.

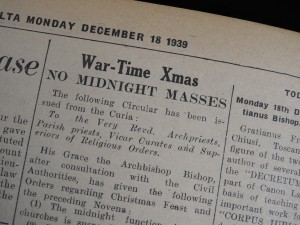

Even though the Maltese Islands were not yet directly involved in war, a foreboding atmosphere crept its way into the lives of people. As if matters were not yet miserable enough, a Bishop’s Circular which was published on The Times of Malta of 17 December 1939 declared that the Christmas midnight function in the churches was to be suspended. The Novena and feast functions could be celebrated from 4:00am onwards provided that no lights were visible from the outside. Those churches which required singers and musicians from far places for the early Christmas function had to apply to the Commissioner of Police for the necessary permits to travel. While it was permissible to give a small sign to the faithful by the ringing of bells for the function of the Novena and Christmas Eve, this had to be done according to predetermined rules.

Even though the Maltese Islands were not yet directly involved in war, a foreboding atmosphere crept its way into the lives of people. As if matters were not yet miserable enough, a Bishop’s Circular which was published on The Times of Malta of 17 December 1939 declared that the Christmas midnight function in the churches was to be suspended. The Novena and feast functions could be celebrated from 4:00am onwards provided that no lights were visible from the outside. Those churches which required singers and musicians from far places for the early Christmas function had to apply to the Commissioner of Police for the necessary permits to travel. While it was permissible to give a small sign to the faithful by the ringing of bells for the function of the Novena and Christmas Eve, this had to be done according to predetermined rules.Albeit the continuous warnings and pleas to adhere strictly to the black-out orders, it seemed that not everyone was following the rules. An announcement on The Times of Malta of the 20 December 1939 issued by the Lieutenant’s Government Office advised the public that the black-out on the night of December 15-16 was not entirely satisfactory, and that there were several lights showing in the Valletta, Sliema, Hamrun, Cospicua and Naxxar districts. Several lights were only put out as aircraft passed overhead. This notice pointed out also that a section of the public could still have been unaware of the black-out rules since they seemed to have been published only on The Times of Malta and Il-Berqa newspapers. Illiterate persons would therefore have had no way of being forewarned except by hearsay. Therefore, a siren warning which was different from the Air-Raid alarm signal, was recommended to be given throughout the islands at sunset.

Letters by readers in the Correspondence section of The Times of Malta of the 20 and 21 December 1939 vent their frustration and contempt at those who were not taking these black-out precautions seriously:

“Many people rather irresponsibly remark that they do not quite see the use of strict black-outs when Germany is at such a distance away. The reply is that precaution is better than cure. I am sure that these people will think very different if they find one day a German bomb dropping at their door-step or in their backyard, just because some stray lights guided an enemy to an objective.” Signed ‘Common-Sense’.

“I am sure that a number of law-abiding citizens in these islands feel that the time has come for coercion to replace coaxing. Those people who scorn to comply with reasonable regulations are either knaves or fools and most dangerous to the community in war time; they should be under lock and key for the duration of the war: either in jail or in a lunatic asylum. The pathetic appeals made by the authorities are becoming nauseating.” Signed Lieutenant Colonel (retired) H. M Marshall.

Special Black-Out arrangements for Christmas and New Year, published on The Times of Malta of the 23 and 30 December 1939, informed the public that the black-out of buildings on the nights of 24 – 27 December and 30 December – 1 January were to be postponed for one and a half hours from midnight. On these nights, motor vehicles were allowed on the road without requiring special permission until 1:30am, and shops and places of entertainment could remain open until 1:00am.

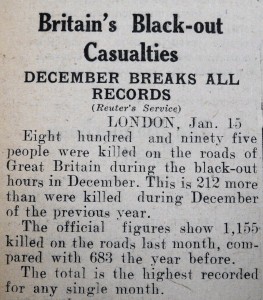

Special Black-Out arrangements for Christmas and New Year, published on The Times of Malta of the 23 and 30 December 1939, informed the public that the black-out of buildings on the nights of 24 – 27 December and 30 December – 1 January were to be postponed for one and a half hours from midnight. On these nights, motor vehicles were allowed on the road without requiring special permission until 1:30am, and shops and places of entertainment could remain open until 1:00am. Possibly few had considered that light could be their enemy until it became essential to extinguish it. There was no mention of accidents or fatalities due to the black-out on the Islands in the December’s Times of Malta newspapers. However, reports from Great Britain relating to the high increase in road fatalities during the night were quite shocking. On 13 December 1939, the British Official Press stated that road fatalities had increased considerably from September to November. Yet the worst scenario took place in December, as reported by the Reuter’s Service on 16 January 1940, when 895 people were killed on the roads of Great Britain during the black-out hours. This was 212 more than those who were killed during December of the previous year.

Possibly few had considered that light could be their enemy until it became essential to extinguish it. There was no mention of accidents or fatalities due to the black-out on the Islands in the December’s Times of Malta newspapers. However, reports from Great Britain relating to the high increase in road fatalities during the night were quite shocking. On 13 December 1939, the British Official Press stated that road fatalities had increased considerably from September to November. Yet the worst scenario took place in December, as reported by the Reuter’s Service on 16 January 1940, when 895 people were killed on the roads of Great Britain during the black-out hours. This was 212 more than those who were killed during December of the previous year.This was surely a strange Christmas to the Maltese people who are accustomed to celebrate these days in a profuse way. Although through no fault of their own, they were involved in war and they had to adapt to war conditions. Alas, much worse was yet to come.

(This article was published in the Christmas Times magazine issued with The Times of Malta dated 13 December 2017)

-

Love in the time of war

A century ago, many countries had to deal with the onset of World War I which was supposed to be the war to end all wars. Yet, a few years later, the reality of World War II ravaged again many people’s lives, as it devastated their motherland, their homes and their existence.

Today, these poignant episodes are recorded in various museums around the world, including the National War Museum in Valletta, wherein one finds several objects which recall these dark periods. However a visit to this museum will reveal that its exhibits are witness to more than that, since they also display how people confronted and survived these crucial moments, and how the ugliness of war never stopped their urge to live and to love.

During a recent visit to this museum wherein I was accompanied by Curator Charles Debono, I discovered how five particular items – a British Empire Medal, an RAF side cap, a uniform jacket, a tankard won at a sports event, and part of a manifold of a P38 Lightning aircraft – formed part of a fantastic narrative relating to a famous English couple who met in Malta and were united and separated by war. Indeed, as I followed the story of the legendary Wg Cdr Adrian Warburton and his lover Christina Ratcliffe, I was whirled back in the 1940s; a time when both the Maltese islands and their inhabitants were pushed to their limits and heroes were borne.

Adrian Warburton was born in Middlesborough on March, 10, 1918, but his father Geoffrey, a young submarine commander who had been awarded the prestigious Distinguished Service Order, decided to christen him in a submarine which was berthed in Malta. Apparently, a good number of Warburton’s family members were renowned for their eccentric behaviour, particularly where war was concerned, and as Tony Spooner said in his book Warburton’s War, “DSO’s were fairly commonplace in the family”.

In fact, during his brief life, even Adrian received this honour twice: one of which was awarded to him for his bravery when flying very low among the Italian battleships and cruisers in Taranto in order to read their names, after the cameras failed to work during a reconnaissance mission. This information enabled the Fleet Air Arm to dispatch an effective attack on the enemy later on that night.

Interestingly, during his training to become a pilot, Adrian had failed to impress his seniors and even though he eventually succeeded to pass his trials, his general assessment was deemed below average. Probably, besides his dare-devil acts, this was also the reason why he crashed his planes during some of his missions. Presumably, this was also the motive for the disbelief that he was dead, after he went missing during his last flight in 1944 …It was on September, 6, 1940 that Warburton arrived in Luqa airfield after he was transferred on duty to Malta. Soon he distinguished himself for his fearless attitude such as when he and his two crewmen shot down an Italian Z.506B seaplane when they were only expected to shoot some photos.

His love story with Christina Ratcliffe took place after she was stranded in Malta, when Italy declared war on Britain and France on 10th June 1940. She had come to our islands together with her group in order to perform as a cabaret dancer but when they found themselves unemployed, these artists set up an ensemble which they called the Whizz Bangs and provided entertainment for the troops.

During her stay on the island, Ratcliffe made friends with a French pilot, Jacques Mehouas, who often spoke to her about Warburton and described him as a brave and formidable British pilot. Ironically, it was his death which brought them together, when Warburton, who was also a friend of his, approached her to give her his condolences. Ratcliffe considered this first encounter as love at first sight since in her later writings she admitted that with his golden hair and his beautiful blue eyes, Warburton resembled a Greek god.

In 1939 Warburton had married Eileen Mitchell after a very brief courtship but allegedly he had left her at once when he found out that she was divorced and had a child. However in Ratcliffe, he discovered a soul mate and soon they became one of the most renowned couples at the time. Like the British pilot, she was beautiful, charismatic and adventurous and as Spooner described them “With their personalities, zest and determination, they were to become living symbols of the island’s unconquerable spirit.”

In fact, besides working as an entertainer, after some time, Christina volunteered to work with the RAF as a telephonist and later as a plotter at the underground War Headquarters in Valletta. She was eventually appointed Captain of D Watch and then became assistant to the Controller, thus having to abandon the Whizz Bangs group.

This love story came to an abrupt end when on April 12, 1944, Warburton was sent on a reconnaissance mission during which he was supposed to take some photos over Germany, but he never returned. At first his disappearance was not given much importance because workmates, friends and even Ratcliffe were expecting him to return like he always did before. Yet by time, this matter became riddled with speculation as people started to question whether he had committed suicide or whether he had simply left his girlfriend and started a new affair.

After this incident, Ratcliffe changed drastically. Her neighbours recall that she became a recluse, preferring to live in isolation in her apartment at 7/3, Vilhena Terrace, Vilhena Street, Floriana, and forever waiting for her Warby to return to her. In his book Women of Malta, Frederick R Galea, states that “her last few years were unhappy ones, trying to drown her loneliness in alcohol; she became withdrawn and impoverished.” Certainly this was a pitiful end to a woman who in 1943 was awarded the British Empire Medal in recognition of her work during World War II. During her lifetime, Ratcliffe donated this medal together with the uniform and the tankard which belonged to her beloved Warburton, to the National War Museum in Valletta.

It was finally in 2002 when Warburton’s fate was identified, after Frank Dorber, a Welsh aviation researcher, discovered his remains in the cockpit of his wrecked plane, buried about two metres deep in a field near the Bavarian village of Egling an der Paar, 34 miles west of Munich. An examination of his aircraft showed that one of the propellers had bullet holes in it, thus indicating that Warburton had been shot down. Part of this plane was donated to the National War Museum in Valletta and now forms part of the exhibits which reflect this story.

Meanwhile, according to Commonwealth regulations, Warburton was given a formal funeral on May 14, 2003 and he was buried at the Durnbach Commonwealth War Cemetery. Curiously, this ceremony was attended also by his wife Eileen whom many believed to have been dead. After Warburton was found and buried, many sympathizers of the couple Warburton – Ratcliffe demanded whether it was time for these two lovers to be re-united, even if after death? But where is Ratcliffe?

A visit to the Addolorata cemetery in Paola where I was accompanied by Eman Bonnici, who is the cemetery’s assistant librarian and a researcher of this site, led me to the resting place of ‘Christina of George Cross Island’. He explained to me that the cemetery’s records show that Ratcliffe was originally buried in the common area of the Commonwealth section in 1988. According to a grave-digger from Floriana, Ratcliffe had become so poor that the neighbours had collected the necessary funds to provide her with a proper burial. Then, in 1991, an individual bearing the surname Ratcliffe, bought a grave for her so that her remains will not be lost in the common ossuary. This grave, marked no. 4, is situated in the East Division, Section MA-D. Bonnici informed me that Ratcliffe’s grave is regularly visited by foreigners, particularly from England and Scotland, who come to this cemetery in order to pay their tribute to a heroine of such a turbulent but fascinating love affair.

(This article was published in ‘Man Matters’ Supplement in The Times of Malta dated 20th September 2014)

-

MINIATURE CHURCH DEVOTION

As several bombs were let loose on our islands during the attacks of World War II, their destructive effects threatened more than human lives and buildings. They put at peril our heritage, jeopardizing the roots of our people and the future of our country.

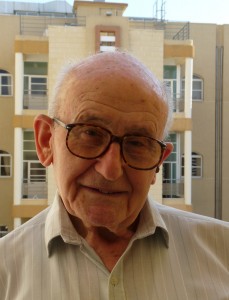

Raphael Micallef, now 82, still recalls the terror felt by the people as the shrill of the air-raid sirens urged them to leave their houses and run for shelters. As an inhabitant of the capital city, he saw his town being shattered to pieces, the damage claiming even unique treasures such as the Chapel of Bones which used to be so popular both with the locals and the tourists. People huddled together in shelters and prayed for their own safety but they also implored for their houses to be spared as these nested within them all their possessions, memories of loved ones, and valuable objects which had been passed on from generation to generation.

Raphael Micallef, now 82, still recalls the terror felt by the people as the shrill of the air-raid sirens urged them to leave their houses and run for shelters. As an inhabitant of the capital city, he saw his town being shattered to pieces, the damage claiming even unique treasures such as the Chapel of Bones which used to be so popular both with the locals and the tourists. People huddled together in shelters and prayed for their own safety but they also implored for their houses to be spared as these nested within them all their possessions, memories of loved ones, and valuable objects which had been passed on from generation to generation.“Valletta and Cottonera suffered some of the severest attacks. Unfortunately within these areas one could find the best examples of church models, many of which had been inherited over many years. Sadly most of them had to be abandoned during the war and almost all of them ended up buried under the rubble of destroyed buildings.”

The craft of church model-making had been introduced to our islands by the Knights of St John back in the 16th century, and therefore it’s knowledge was a distinct tradition. However the adversity of war ravaged even this ancient memory until eventually this craft was almost completely forgotten.

In 1986, this dire situation inspired Raphael, who was an avid enthusiast in church model-making, to make an effort to revive this craft. Together with his friends Tony Terribile and Paul Piscopo, he ventured to initiate an association under the name of Għaqda Dilettanti Mudelli ta’ Knejjes which aimed to instill interest, knowhow and craftsmanship in the art of church model-making. The first president of the association was Guido Lanfranco.

“After 26 years, I am proud to say that now we have our own premises at 37 East Street, Valletta. Although it is a small place, our 400 members meet keenly under its humble roof in order to attend to the regular activities that we organize. Members’ ages differ greatly; starting from young children of 7 and going up to elderly individuals over 90. Everybody is welcome in our group and together we learn and discuss new ideas of how to enrich this cultural tradition. Each of the members has the opportunity to explore his skills and to enhance them further both through the interaction with other members and also under the guidance of craftsmen and historians who are frequently invited to our premises. Many members have built their own church models, some of which one can even walk through – a popular model is that of Simon Mercieca which is often open to the public for viewing. Others have opted to produce statues and accessories which are used in the church models. Most of the members succeed in producing marvellous works, sometimes using common objects and transforming them into intricate decorations which adorne the models.”

“After 26 years, I am proud to say that now we have our own premises at 37 East Street, Valletta. Although it is a small place, our 400 members meet keenly under its humble roof in order to attend to the regular activities that we organize. Members’ ages differ greatly; starting from young children of 7 and going up to elderly individuals over 90. Everybody is welcome in our group and together we learn and discuss new ideas of how to enrich this cultural tradition. Each of the members has the opportunity to explore his skills and to enhance them further both through the interaction with other members and also under the guidance of craftsmen and historians who are frequently invited to our premises. Many members have built their own church models, some of which one can even walk through – a popular model is that of Simon Mercieca which is often open to the public for viewing. Others have opted to produce statues and accessories which are used in the church models. Most of the members succeed in producing marvellous works, sometimes using common objects and transforming them into intricate decorations which adorne the models.”Each year, during the Lenten period, the association organizes an exhibition with some of the works of the members, both to give them the opportunity to share their skill with others and also to attract the public to this old tradition.

“Our association is deeply cherished by its members. In fact some of them have honoured us by donating us prestigious works which belonged to them or to their families. It is a great privilege to possess a number of the few lucky survivors of war which managed to make it, as their owners lovingly took them along with them to safer areas.”

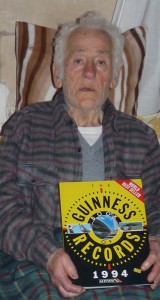

Raphael showed me some of these examples, including an elegant limestone church facade which was designed by Manuel Psaila between 1935 and 1940, and a delicate niche produced out of quilling which dates back to more than 100 years. I was thankful to Raphael for having shared with me this experience. His calm and serene smile was full of pride as his dream of giving the life back to a part of our culture was fulfilled. In fact the association’s work has succeeded to reach much further grounds than any of the members could ever have aspired for, when in 1994, Joseph Sciberras ended up winning a place in the Guinness Book of Records for his church model which was made out of more than 3 million used up matchsticks!

Raphael showed me some of these examples, including an elegant limestone church facade which was designed by Manuel Psaila between 1935 and 1940, and a delicate niche produced out of quilling which dates back to more than 100 years. I was thankful to Raphael for having shared with me this experience. His calm and serene smile was full of pride as his dream of giving the life back to a part of our culture was fulfilled. In fact the association’s work has succeeded to reach much further grounds than any of the members could ever have aspired for, when in 1994, Joseph Sciberras ended up winning a place in the Guinness Book of Records for his church model which was made out of more than 3 million used up matchsticks!I met Joseph Sciberras, now 93, in his son’s home in Attard. Sitting cosily near his bird pet who sung cheerfully at his side, Joseph told me the story of his model which has given him so much satisfaction in his life.

“I was an electrician by trade but during the war I was engaged as a soldier. I remember vividly a particular day when I was at work in Delimara and came to know that Floriana, where I lived, had just been badly hit by bomb attacks. I was desperate to see whether my family was safe and whether our house was damaged, and my superior allowed me to leave. I walked right back to Floriana there and then, and luckily both my family and my house were safe. The enemy used to target his attacks from the Floriana parish church and bomb throughout. We lived nearby and one day our house did fall victim to these attacks, alas like the church which did too anyway.

Years passed and both our houses and the Floriana parish church were rebuilt. I used to like to observe the facade of our beloved church and when I became a pensioner, I decided to start building an exact model of it. I chose to construct it out of used up matchsticks. Day after day, I worked on my model, constantly taking measures and designing the acute details of the facade.

Years passed and both our houses and the Floriana parish church were rebuilt. I used to like to observe the facade of our beloved church and when I became a pensioner, I decided to start building an exact model of it. I chose to construct it out of used up matchsticks. Day after day, I worked on my model, constantly taking measures and designing the acute details of the facade.When my friends who most of them worked at the Dockyards got to know what I was doing, they started to collect used mathsticks for me. Then when I exhibited my first model to the public, these matchsticks began to arrive from different areas of Malta! I had so many in hand that I ended up doing all the parish church inside out, until eventually the model measured 2 metres by 2 metres with a height of a further 1.5 metres.

People were totally mesmerized by my model and many, including several tourists, even hugged me when they noticed all the details and work that I had put into my work. It was during one of these exhibitions when some foreigners entered to view my model. I could not be more lucky as these were officials of the Guinness Book of Records and as they studied and measured my model, they informed me that I had succeeded to break the record of the previous winner matchstick model! Soon a certificate arrived together with my inclusion in the Guinness Book of Records.” Spiritedly Joseph showed me his model church displayed on the pages of this famous book. He felt very satisfied that his hard work which took so many years to do was given such an acknowledgement.

People were totally mesmerized by my model and many, including several tourists, even hugged me when they noticed all the details and work that I had put into my work. It was during one of these exhibitions when some foreigners entered to view my model. I could not be more lucky as these were officials of the Guinness Book of Records and as they studied and measured my model, they informed me that I had succeeded to break the record of the previous winner matchstick model! Soon a certificate arrived together with my inclusion in the Guinness Book of Records.” Spiritedly Joseph showed me his model church displayed on the pages of this famous book. He felt very satisfied that his hard work which took so many years to do was given such an acknowledgement.“Ultimately this model became part of my life as I have dedicated much of my love and my time to it. In return it gave me happinness as I saw people admiring it and appreciating my skill and patience. I have taken good care of it all along these years and my final wish is to donate my model to our National Museum of Etnography wherein it could be enjoyed by the public in reminiscence of me and of this ancient cultural tradition. I feel sad to leave it behind me but one cannot live forever, can he?”

I could not resist the invitation of Francis, Joseph’s son, to visit the workshop of his father in Floriana wherein this model was stored. Humorously Francis indicated the name of the place “Sulfarina” (matchstick). “Interestingly our family was originally known as “Taċ-Ċomb” (of lead) but today, because of my father’s model, everyone knows us as “Tas-Sulfarini” (of the matchsticks). Notwithstanding that my father has stopped working now, I still find packets full of used matchsticks which people leave behind his door.”

I could not resist the invitation of Francis, Joseph’s son, to visit the workshop of his father in Floriana wherein this model was stored. Humorously Francis indicated the name of the place “Sulfarina” (matchstick). “Interestingly our family was originally known as “Taċ-Ċomb” (of lead) but today, because of my father’s model, everyone knows us as “Tas-Sulfarini” (of the matchsticks). Notwithstanding that my father has stopped working now, I still find packets full of used matchsticks which people leave behind his door.”We went into the small building which was totally engulfed by the huge model of the Floriana parish church and by other of Joseph’s works, all made of matchsticks. With some difficulty, Francis managed to find his way through the multitude of wires which his father had included in the model in order to light up the church.

Now I could observe what Joseph had talked about…. the millions of matchsticks, each one placed or thwarted to fit into the shape that he had designed for them…. the facade, the dome, the walls, the columns, the niches, the floor, the minute chairs. There were also small silver apostles which Francis had made for his father to place on the altar. Miniature gorgeous chandeliers made up of common scrap hung beautifully along the flowing arches. It was all set up and ready as if inviting people to go inside.

Now I could observe what Joseph had talked about…. the millions of matchsticks, each one placed or thwarted to fit into the shape that he had designed for them…. the facade, the dome, the walls, the columns, the niches, the floor, the minute chairs. There were also small silver apostles which Francis had made for his father to place on the altar. Miniature gorgeous chandeliers made up of common scrap hung beautifully along the flowing arches. It was all set up and ready as if inviting people to go inside.I gazed inside the model church, my eyes resting and enjoying every detail whilst I slowly understood what this all means… Within this modest model lied the admirable representation of our local skills together with the ability of our people to prevail even through the hardest times.

For further information about the Għaqda Dilettanti Mudelli ta’ Knejjes, one can access their website www.freewebs.com/ghaqda_dilettanti_knejjes or join their facebook page.

(Note: An edited version of this article was published in FIRST magazine Issue April 2012. A pdf version of the published article is available on this website under the title MINIATURE CHURCH DEVOTION).

-

THE NATIVITY IN MINIATURE

When the last month of the year steals its way into our hearts, we find ourselves in a world of light, colours, dreams, hopes and Christmas… and nothing symbolises the

Christmas spirit better than the nativity scene captured in a traditional crib. Fiona Vella went in search of two remarkable examples of this long-standing Maltese tradition.

Christmas spirit better than the nativity scene captured in a traditional crib. Fiona Vella went in search of two remarkable examples of this long-standing Maltese tradition.As December comes round, out come the boxes loaded with colourful accessories and delights which were stored away the previous year: a disassembled Christmas tree, some intricate ornaments and a few old cherished cards.

Yet nothing compares to the allure of a precious crib with its little figurines and the statuette of baby Jesus which needs to be warmed up with Ġulbiena, at least in a country with a strong Christian

tradition like Malta. The annual ritual of setting up the crib is fascinating, but what is this enigmatic fascination which draws us each year to recreate this nativity scene? To unearth this riddle I decided to go back to our roots, seeking out two beautiful antique treasures which lie within our intriguing island.

tradition like Malta. The annual ritual of setting up the crib is fascinating, but what is this enigmatic fascination which draws us each year to recreate this nativity scene? To unearth this riddle I decided to go back to our roots, seeking out two beautiful antique treasures which lie within our intriguing island.MDINA

The first gem is situated deep in the heart of the medieval town of Mdina, shielded in the core of St Peter’s Monastery, the domicile of the Benedictine Cloistered Nuns.

With the aid of Joseph Flask, a diligent writer about the life and history of the Benedictine Monastic Order, I was allowed to meet the Rev. Mother Abbess Sr. Maria Adeodata Testaferrata de Noto OSB who received me warmly and invited me to view the oldest known static crib in Malta.

The monastery itself is a magnificent historic and architectural site, dating back to the 15th century. Nevertheless the experience of stepping inside a location which is customarily prohibited to

outsiders’ eyes took that sense of magnificence one step further.

outsiders’ eyes took that sense of magnificence one step further.Up the stairs and along the innermost corridors, lying dormant behind a wide glass case and heavy curtains was my ‘prize’, and I was overwhelmed with emotion as I beheld this rarely seen fine example of one of the highest Maltese traditions.

No one knows who was its original creator or when it was built, but probably the crib’s first restoration took place in 1826, as the earliest painted signature G.B.G

indicates. A similar unspecified restorer enlarged the crib in 1846 and left a simple mark of G.G. A final revamp dates back to 1977, this time clearly signed by Giuseppe Sammut who painted and added the crib’s scenery.

indicates. A similar unspecified restorer enlarged the crib in 1846 and left a simple mark of G.G. A final revamp dates back to 1977, this time clearly signed by Giuseppe Sammut who painted and added the crib’s scenery.Incredibly, while we were exploring the crib, we chanced upon another signature which Joseph had never noticed before – a coarse reddish scribbling bearing the initials G.G and a not so clear G.I. Evidently the crib seems to hold even more challenges and clues for devotees to decipher.

The crib is embedded with personal memories of several people. In fact, a closer glimpse at its figurines lying around the

unrefined landscape made of glued old sacks and newspapers, reveals that oddly most of the figures do not match each other, either in style, age or even size! This effect was initiated by the nuns themselves when they resolved to bestow the original crib’s population with every relative statuette that came in their possession! Amusingly, more intense exploration discloses even extraneous insertions; such as the Greek classic statuette and an irrelevant building situated at the back. Peculiar as it might seem, this reality exudes a tender feeling as one realizes that the crib actually encompasses the love and memories of each nun that lived with it.

unrefined landscape made of glued old sacks and newspapers, reveals that oddly most of the figures do not match each other, either in style, age or even size! This effect was initiated by the nuns themselves when they resolved to bestow the original crib’s population with every relative statuette that came in their possession! Amusingly, more intense exploration discloses even extraneous insertions; such as the Greek classic statuette and an irrelevant building situated at the back. Peculiar as it might seem, this reality exudes a tender feeling as one realizes that the crib actually encompasses the love and memories of each nun that lived with it.The crib is in fact of somewhat crucial help to the cloistered nuns, helping them to evoke the

meaning behind the holy birth; a tangible item in a life withdrawn from the usual worldly pleasures, which constantly reminds them of the sweet joy of Christmas. Indeed, this very crib inspired the renowned short writings of the Blessed Maria Adeodata Pisani OSB who lived in the monastery for several years. And to this day, the crib continues to instigate the spirits of the other nuns when on Christmas Eve they celebrate a traditional procession which ends up in front of it.

meaning behind the holy birth; a tangible item in a life withdrawn from the usual worldly pleasures, which constantly reminds them of the sweet joy of Christmas. Indeed, this very crib inspired the renowned short writings of the Blessed Maria Adeodata Pisani OSB who lived in the monastery for several years. And to this day, the crib continues to instigate the spirits of the other nuns when on Christmas Eve they celebrate a traditional procession which ends up in front of it.ŻEJTUN

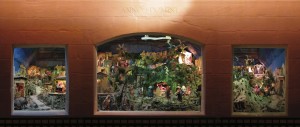

The other route to discovery led me to the quaint village of Żejtun, again to another convent but this time to see the oldest, large, Maltese mechanical crib, which dates back to 1945, a period wherein

our island lay ravaged from the destruction of World War II. It was this devastation that inspired Mons. Emmanuel Galea to create a unique religious symbol as he saw that people desperately needed to rekindle their faith and hope of a better life.

our island lay ravaged from the destruction of World War II. It was this devastation that inspired Mons. Emmanuel Galea to create a unique religious symbol as he saw that people desperately needed to rekindle their faith and hope of a better life.Together with his nephew Pawlu Pavia he devised a plan to build a large mechanical crib which could be motor-driven.

I found Pawlu, now 86, residing in St Vincent De Paule’s residence. Despite his old age, he reconstructed the whole story with sharp clarity and also with a touch of melancholy.

He remembers how some workers were brought in to build a platform made from random pieces of broken doors and windows. Moreover, three openings were cut in one of the room’s wall as the crib

had to represent three sections: what happened before the birth of Jesus Christ, the actual birth itself and what occurred thereafter.

had to represent three sections: what happened before the birth of Jesus Christ, the actual birth itself and what occurred thereafter.The fabrication of papier machè and the layout of the crib he made with the bishop, while he alone was responsible for building the crib’s figurines from wood and iron wire. However the hardest task

was to find some ingenious way of motorizing the figurines’ movements and to actually interelate them at a time when resources were very few. Another difficulty was to surpass the dilemma of an unstable electric current. Incredibly he did all this by means of one single motor which he succeeded to find in a remote shop. Even more incredible is that after 65 years, the crib still functions with this same system!

was to find some ingenious way of motorizing the figurines’ movements and to actually interelate them at a time when resources were very few. Another difficulty was to surpass the dilemma of an unstable electric current. Incredibly he did all this by means of one single motor which he succeeded to find in a remote shop. Even more incredible is that after 65 years, the crib still functions with this same system!This journey also led me to Sister Pawlina Gauci, now 78, who, together with the late Sr. Angela, had the responsibility of dressing the figures. Her three years

missionary work in Persia (now Iran) aided her with good knowledge of the type of material to be used and one by one the figures were clothed with several samples of fabric which a number of shops had contributed.

missionary work in Persia (now Iran) aided her with good knowledge of the type of material to be used and one by one the figures were clothed with several samples of fabric which a number of shops had contributed.Both Pawlu and Sr. Pawlina recall the commotion that this crib raised when it was opened to the public for the first time during Christmas of 1947. Visitors came from all over Malta and there was such a big crowd that the police had to intervene to keep control of the situation!

Now that Pawlu is retired, the crib passed into the care of his nephew Joseph Pavia,

whose great dedication to it is no lesser than his uncle’s. In fact during the last years Joseph renovated the visitors’ room and included a very interesting documentary which recounts the whole story of this crib in five different languages.

whose great dedication to it is no lesser than his uncle’s. In fact during the last years Joseph renovated the visitors’ room and included a very interesting documentary which recounts the whole story of this crib in five different languages.Remarkably, even this crib seems to bear the destiny to be associated with holiness as currently there is the process of the cause for canonization of its instigator, Mons. Emmanuel Galea.

As I left the crib, I pondered about the dedication and devotion behind their creation. The endeavour, the ritual, the almost childish happiness to share a crib with others… all lead to an ancient dream

which St Francis of Assisi had foreseen a long time ago in the village of Greccio. For through its modesty, a crib reminds us that the spirit of Christmas is simple and that it is meant to reach out to our hearts and souls and bathe them in the joy of the birth of Jesus.

which St Francis of Assisi had foreseen a long time ago in the village of Greccio. For through its modesty, a crib reminds us that the spirit of Christmas is simple and that it is meant to reach out to our hearts and souls and bathe them in the joy of the birth of Jesus.(This article was published in FIRST magazine, Issue December 2010. FIRST magazine is delivered with The Malta Independent on Sunday)

Travelogue

Archives

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jan | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

Recent Posts

- A MATTER OF FATE

- MALTA’S PREHISTORIC TREASURES

- THE MAGIC IS IN THE DETAIL

- THE SELLING GAME

- NEVER FORGOTTEN

- Ġrajjiet mhux mitmuma – 35 sena mit-Traġedja tal-Patrol Boat C23

- AN UNEXPECTED VISIT

- THE SISTERS OF THE CRIB

Comments

- Pauline Harkins on Novella – Li kieku stajt!

- admin on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Albert on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Martin Ratcliffe on Love in the time of war

- admin on 24 SENA ILU: IT-TRAĠEDJA TAL-PATROL BOAT C23