-

To die for a piece of bread

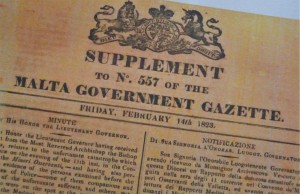

Although Carnival is generally associated with fun, exuberance and colour, it was sadness, tragedy and darkness which marked this festive season on 11th February 1823, after more than a hundred children died in Valletta. Details of this terrible tragedy are immortalized in black and white in the Malta Government Gazette of Friday, 14th February 1823 which is archived at the National Library of Malta in Valletta.

Initially, news of this tragedy was recorded as a Government Notice in the Malta Government Gazette (No. 557) by Richard Plasket, Chief Secretary to Government, wherein he declared that an investigation was taking place in order to obtain any possible evidence regarding this fatal accident. A published report of these findings was later annexed as a Supplement (pp. 3391-2) to the same journal of 14th February 1823.

In this long report, Plasket includes information that was provided to him by the Archbishop of Malta, persons examined before the Magistrates of Police which comprised both relatives of the victims and other individuals who were present during this incident, and also a medical report related to this case.

At the beginning of this statement, he furnishes a context for this mishap wherein he mentions that in those years, during the last days of the Carnival celebrations, it had become a tradition to gather a group of boys aged from 8 to 15, who came from the lower classes of Valletta and the Three Cities, to participate in a particular activity. In this event, children who opted to join were taken in a procession to Floriana or elsewhere, and after attending mass, they received some bread which was financed by the Government and other beneficiaries. The main aim of this activity was to protect the children by keeping them out of the riot and confusion of the Carnival that took place in the streets of these cities. The arrangement of this procession was under the responsibility of the Ecclesiastical Directors who taught Cathecism.

At the beginning of this statement, he furnishes a context for this mishap wherein he mentions that in those years, during the last days of the Carnival celebrations, it had become a tradition to gather a group of boys aged from 8 to 15, who came from the lower classes of Valletta and the Three Cities, to participate in a particular activity. In this event, children who opted to join were taken in a procession to Floriana or elsewhere, and after attending mass, they received some bread which was financed by the Government and other beneficiaries. The main aim of this activity was to protect the children by keeping them out of the riot and confusion of the Carnival that took place in the streets of these cities. The arrangement of this procession was under the responsibility of the Ecclesiastical Directors who taught Cathecism.Indeed, according to this tradition, on the 10th February 1823, some children were taken to attend mass at Floriana and were then accompanied to the Convent of the Minori Osservanti in Valletta (today known as the Convent of the Franciscans of St Mary of Jesus or Ta’ Ġieżu) where they were given bread without any difficulty or trouble. The same ritual was intended to take place the day after. Yet no one had any idea that a series of errors would eventually lead to such a great tragedy.

Everything started according to plan on 11th February 1823. The children were gathered in a group and were taken to mass at Floriana. However, when the ceremony lasted an hour longer than usual, the children’s procession to the Convent in Valletta coincided with the end of the Carnival celebrations, when a great number of jubilant people were returning home. This led to the next blunder, as a number of adults and children who were passing by and who knew of this tradition, secretely mixed in with the other boys in order to share the bread which would be distributed.

Everything started according to plan on 11th February 1823. The children were gathered in a group and were taken to mass at Floriana. However, when the ceremony lasted an hour longer than usual, the children’s procession to the Convent in Valletta coincided with the end of the Carnival celebrations, when a great number of jubilant people were returning home. This led to the next blunder, as a number of adults and children who were passing by and who knew of this tradition, secretely mixed in with the other boys in order to share the bread which would be distributed.In line with the usual arrangement, these boys were to enter into a corridor of the Convent from the door of the vestry of the Church, and were to be let out through the opposite door of the Convent in St Ursula Street, where the bread was to be distributed. In order to prevent the boys who received their share from reentering to take a second helping of bread, it became customary to lock the door of the vestry. Yet this time, since the children were late, this door was left open for a longer time so that they could enter. As the sun was setting and darkness crept in, nobody realized that other men and boys who did not form part of the original group were entering too.

Soon, the boys who were queuing in the corridor found themselves being pushed by these trespassers as they forced themselves in. The situation worsened when eventually the vestry door was closed as usual and the children were shoved further at the end of the corridor where a door stood half open so that no one could get back in a second time.

That day was certainly ill-fated when further mistakes continued to occur. In fact, a lamp which was usually lit in the corridor was somehow put out, leaving the overcrowded area in total darkness. This confused the people even more and as they tried to push themselves forward in order to get out, the boys who were at the front fell down a flight of eight steps on top of each other, thereby blocking further the door which happenned to open inwards.

Suddenly, both those who were distributing the bread and the Convent’s neighbours began to hear children shrieking out. They ran to give their assistance but a lot of time was wasted as they tried to open the two doors which led to the corridor in order to reach the people inside.

Eventually, many children were taken out fainting but recovered soon. Others appeared lifeless but were brought to their senses some time afterwards. Regretfully, 110 boys from 8 to 15 years of age perished from suffocation when they were pressed together in such a small place or because they were trampled upon.

After investigating this accident, the Lieutenant Governor concluded that this was an unfortunate accident caused by the succession of errors mentioned above. Consequently, no one was accused for the death of these children since these acts were not done on purpose to harm them. In fact, Plasket commented that everyone had collaborated to assist these poor boys and even the victims’ relatives had allowed the police and the soldiers to work speedily and diligently in order to save as many children as possible. He insisted that were it not for this, the tragedy could have been much worse.

After investigating this accident, the Lieutenant Governor concluded that this was an unfortunate accident caused by the succession of errors mentioned above. Consequently, no one was accused for the death of these children since these acts were not done on purpose to harm them. In fact, Plasket commented that everyone had collaborated to assist these poor boys and even the victims’ relatives had allowed the police and the soldiers to work speedily and diligently in order to save as many children as possible. He insisted that were it not for this, the tragedy could have been much worse.As I followed further this narrative by focusing on the names mentioned in Plasket’s report, I succeeded to trace the Captain of the Malta Fencibles who led the soldiers during this tragic moment. It was his descendant, Marquis Nicholas De Piro who led me to see Colonel Marquis Giuseppe De Piro’s portrait which is located at Casa Rocca Piccola in Valletta.

An interesting discussion ensued between us during which the present Marquis informed me also about General Sir George Whitmore who headed the Royal Engineers’ detachment on Malta as its Colonel Commandant between 1811 and 1829. Whitmore had written about his experiences in Malta and had also produced some illustrations related to our islands. Interestingly, Marquis Nicholas De Piro was in possession of a copy of one of these ancient illustrations in the form of a very small slide, which showed some individuals being trampled upon by a group of other people. He wondered whether this slide could be portraying this misfortunate accident of the Carnival of 1823. Yet no children are included in this representation and so it is not clear whether it actually depicts this narrative.

An interesting discussion ensued between us during which the present Marquis informed me also about General Sir George Whitmore who headed the Royal Engineers’ detachment on Malta as its Colonel Commandant between 1811 and 1829. Whitmore had written about his experiences in Malta and had also produced some illustrations related to our islands. Interestingly, Marquis Nicholas De Piro was in possession of a copy of one of these ancient illustrations in the form of a very small slide, which showed some individuals being trampled upon by a group of other people. He wondered whether this slide could be portraying this misfortunate accident of the Carnival of 1823. Yet no children are included in this representation and so it is not clear whether it actually depicts this narrative.My research ended at Ta’ Ġieżu Church and I watched in silence the area where these children lost their lives. Sadness engulfed me when I climbed up the steps on my way back while pondering how these children could end in this way for a piece of bread.

(This article was published in the Carnival Supplement issued with the Times of Malta dated 3rd February 2016)

Category: Times of Malta | Tags: 14th February 1823,1823,Captain of the Malta Fencibles,Carnival,Casa Rocca Piccola,Cathecism,Colonel Marquis Giuseppe De Piro,Convent of the Franciscans of St Mary of Jesus,Convent of the Minori Osservanti,Fiona Vella,Floriana,General Sir George Whitmore,Malta,Marquis Nicholas De Piro,National Library of Malta,Richard Plasket,Royal Engineers’ detachment,ta’ Ġieżu,Three Cities,tragedy,Valletta