Posts Tagged ‘Marquis Nicholas De Piro’

-

Guests to history

One would probably spare only a few moments of consideration at the receipt of a wedding invitation. However, for Baron Igino de Piro d’Amico Inguanez, these endearing solicitations were cherished so much that he kept a collection of them, neatly separated according to their date and wrapped up together by a string.

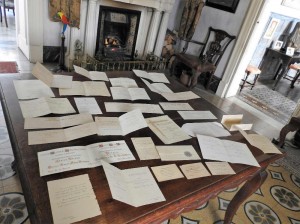

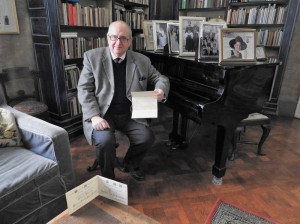

“Were it not for my grandfather’s interest to keep these wedding invitations, we would have lost this fascinating information which can be unravelled within each one of them,” remarked Marquis Nicholas de Piro as we walked towards an elegant table in one of the rooms at Casa Rocca Piccola where he had layed out a number of these invitations.

“Were it not for my grandfather’s interest to keep these wedding invitations, we would have lost this fascinating information which can be unravelled within each one of them,” remarked Marquis Nicholas de Piro as we walked towards an elegant table in one of the rooms at Casa Rocca Piccola where he had layed out a number of these invitations.I glanced out at the wide selection of wedding invitations tastefully set on the polished wooden surface, noticing the different sizes, shapes, writing, designs and paper. The earliest ones dated back to 1815, 1829 and 1832. They were quite plain and small, slightly bigger than a credit card, and written in Italian.

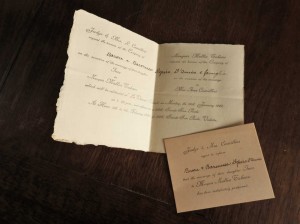

“Here are two of the prettiest ones” said the Marquis as he pulled them out of the rest.

These two invitations had been issued at the end of the 19th century. They were larger than the earlier ones and were quite different from each other. The one dated June 1896 was elegantly designed with an intricate cross at its corner and consisted of an invitation to the wedding between the noble Maria de Piro and Dr. Alfredo Stilon. The other one dated October 1899 was more colourful and rather than an invitation, it was more an announcement of the wedding which was to take place between the noble Maria Teresa de Piro and the Marquis Paolo Apap Bologna. Once again, both were written in Italian.

“Now look at this note which accompanies this wedding invitation,” said the Marquis as he handed it to me.

“Now look at this note which accompanies this wedding invitation,” said the Marquis as he handed it to me.The presentation of this wedding invitation was simpler than the previous two and the writing was in English. Here, Judge and Mrs L Camilleri were requesting the company of Baron and Baroness I de Piro d’Amico Inguanez and family to the wedding of their noble daughter Inez to Marquis Mallia Tabone on 26th January 1920. Yet this celebration was not destined to take place as a smaller card which was sent some days later informed those invited that this wedding had been indefinitely postponed.

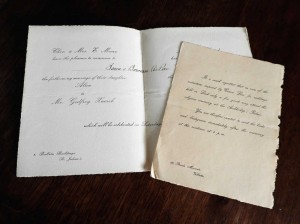

“From these invitations, one can also observe the traditional customs of the various eras. For example, this wedding invitation dated 1935 shows clearly that people who chose to get married during the period of Lent had to abide to some limitations.”

“From these invitations, one can also observe the traditional customs of the various eras. For example, this wedding invitation dated 1935 shows clearly that people who chose to get married during the period of Lent had to abide to some limitations.”Indeed, a formal note which was inserted together with the wedding invitation that was sent by Chev & Mrs E Moore and Mrs H Xuereb to announce the marriage of their daughter Alice Moore to Godfrey Xuereb, provided this information with direct instructions:

‘It is much regretted that in view of the restrictions imposed by Canon Law for weddings held in Lent, only a few guests may attend the religious ceremony at the Archbishop’s Palace.

You are therefore invited to meet the bride and bridegroom immediately after the ceremony at the residence at 4:00pm.’

As we followed the different invitations that were sent along the years to Baron Igino and his family, we could also trace some of his friends and acquaintances, their residences, the chapels and churches where the marriages took place, and the selected locations for the wedding receptions. Although many of the churches still exist today, some of the street names had changed from Italian to English or were altered completely. A number of the residences mentioned have become quite renowned today whilst a few others were turned into commercial properties. Sadly, some of the lovely villas which provided exquisite entertainment in the bygone days were demolished to make place for large modern complexes.

As we followed the different invitations that were sent along the years to Baron Igino and his family, we could also trace some of his friends and acquaintances, their residences, the chapels and churches where the marriages took place, and the selected locations for the wedding receptions. Although many of the churches still exist today, some of the street names had changed from Italian to English or were altered completely. A number of the residences mentioned have become quite renowned today whilst a few others were turned into commercial properties. Sadly, some of the lovely villas which provided exquisite entertainment in the bygone days were demolished to make place for large modern complexes. Amongst these, there was the wedding between Hilda Scicluna and Paymaster Lieutenant W Eric Brockman that took place on 4th March 1928. Their marriage was celebrated at the Archbishop’s Palace in Valletta which seems to have been quite a popular venue for such occasions. On the other hand, the reception was held at the bride’s parents residence that was located at 86 Strada Merkanti Valletta; a house which originally belonged to Sir Oliver Starkey, Bali of Aquila and Latin Secretary to Grand Master La Valette. Being an English Knight, he had assisted the Grand Master during the Great Siege of 1565 and was later given the privilege to be buried in the crypt of the Co-Cathedral of St John in Valletta, close to La Valette’s own burial place.

Amongst these, there was the wedding between Hilda Scicluna and Paymaster Lieutenant W Eric Brockman that took place on 4th March 1928. Their marriage was celebrated at the Archbishop’s Palace in Valletta which seems to have been quite a popular venue for such occasions. On the other hand, the reception was held at the bride’s parents residence that was located at 86 Strada Merkanti Valletta; a house which originally belonged to Sir Oliver Starkey, Bali of Aquila and Latin Secretary to Grand Master La Valette. Being an English Knight, he had assisted the Grand Master during the Great Siege of 1565 and was later given the privilege to be buried in the crypt of the Co-Cathedral of St John in Valletta, close to La Valette’s own burial place.The Cathedral in Mdina seems to have been another prominent place for marriages. On 24th January 1937, Adelina Maempel was married to Edwin England Sant Fournier. A reception followed at Villa Luginsland in 26 Boschetto Road, Rabat; a lovely villa which was built by Baron Max von Tucker, the German consul who was serving in Malta in the early 20th century. Unfortunately in recent years years, this remarkable place was in an abandoned state and had a haunting atmosphere.

The only wedding invitation which came from Gozo looked quite distinguished and it boasted a silver wax seal. The marriage of Carmela and Paul Vella took place on 4th August 1937 and their reception was organized at the Duke of Ediburgh Hotel in Victoria, Gozo. Alas, in recent years, this splendid hotel that was beautifully constructed in Victorian architecture was demolished in order to make way for a commercial centre and a number of residential units.

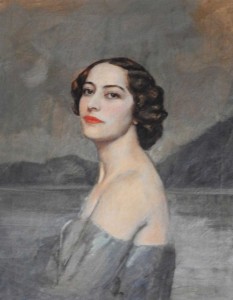

The only wedding invitation which came from Gozo looked quite distinguished and it boasted a silver wax seal. The marriage of Carmela and Paul Vella took place on 4th August 1937 and their reception was organized at the Duke of Ediburgh Hotel in Victoria, Gozo. Alas, in recent years, this splendid hotel that was beautifully constructed in Victorian architecture was demolished in order to make way for a commercial centre and a number of residential units.“As you have already noted, some of these wedding invitations pertained to our relatives. Incidentally, this one which announces the marriage between my aunt Mona de Piro to Major John E J Nelson on 28th December 1940 is a favourite of mine, particularly because she was quite a character and she kept her high spirits even when she was aged more than ninety. Well, she’s there, looking at us!” the Marquis exclaimed as he pointed to a delightful portrait on the opposite wall.

My eyes met with those of a young, graceful girl, defiantly posing with an off-the-shoulder silver dress which melted in the greyish background behind her.

“That portrait created much talk when her relatives saw it since it was regarded too sensual at the time. It was commissioned by her Italian boyfriend, Marquis Onofrio Bartolini Salinbeni, and the painting was done by Arthur Acton who lived in a palace in Florence. Onofrio was madly in love with Mona but unfortunately, their relationship ended and when she returned to Malta, a relative of hers went to Italy to claim this painting since it was not deemed fit for him to keep it,” smiled the Marquis as he went to add some logs to the fire burning in the stylish hearth besides us.

“That portrait created much talk when her relatives saw it since it was regarded too sensual at the time. It was commissioned by her Italian boyfriend, Marquis Onofrio Bartolini Salinbeni, and the painting was done by Arthur Acton who lived in a palace in Florence. Onofrio was madly in love with Mona but unfortunately, their relationship ended and when she returned to Malta, a relative of hers went to Italy to claim this painting since it was not deemed fit for him to keep it,” smiled the Marquis as he went to add some logs to the fire burning in the stylish hearth besides us.A warm gush of air embraced the room as the logs protested and cracked and poured a glowing light over the wedding invitations lying in front of us. For a short spell, I thought that I could hear the tinkling of the glasses filled with red velvety wine and golden sizzling champagne as the guests toasted to the newly married couples.

(This article was published in the Weddings Supplement issued with The Sunday Times of Malta dated 13th March 2016)

-

To die for a piece of bread

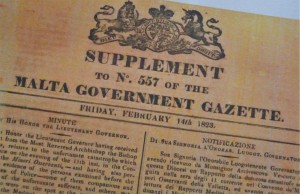

Although Carnival is generally associated with fun, exuberance and colour, it was sadness, tragedy and darkness which marked this festive season on 11th February 1823, after more than a hundred children died in Valletta. Details of this terrible tragedy are immortalized in black and white in the Malta Government Gazette of Friday, 14th February 1823 which is archived at the National Library of Malta in Valletta.

Initially, news of this tragedy was recorded as a Government Notice in the Malta Government Gazette (No. 557) by Richard Plasket, Chief Secretary to Government, wherein he declared that an investigation was taking place in order to obtain any possible evidence regarding this fatal accident. A published report of these findings was later annexed as a Supplement (pp. 3391-2) to the same journal of 14th February 1823.

In this long report, Plasket includes information that was provided to him by the Archbishop of Malta, persons examined before the Magistrates of Police which comprised both relatives of the victims and other individuals who were present during this incident, and also a medical report related to this case.

At the beginning of this statement, he furnishes a context for this mishap wherein he mentions that in those years, during the last days of the Carnival celebrations, it had become a tradition to gather a group of boys aged from 8 to 15, who came from the lower classes of Valletta and the Three Cities, to participate in a particular activity. In this event, children who opted to join were taken in a procession to Floriana or elsewhere, and after attending mass, they received some bread which was financed by the Government and other beneficiaries. The main aim of this activity was to protect the children by keeping them out of the riot and confusion of the Carnival that took place in the streets of these cities. The arrangement of this procession was under the responsibility of the Ecclesiastical Directors who taught Cathecism.

At the beginning of this statement, he furnishes a context for this mishap wherein he mentions that in those years, during the last days of the Carnival celebrations, it had become a tradition to gather a group of boys aged from 8 to 15, who came from the lower classes of Valletta and the Three Cities, to participate in a particular activity. In this event, children who opted to join were taken in a procession to Floriana or elsewhere, and after attending mass, they received some bread which was financed by the Government and other beneficiaries. The main aim of this activity was to protect the children by keeping them out of the riot and confusion of the Carnival that took place in the streets of these cities. The arrangement of this procession was under the responsibility of the Ecclesiastical Directors who taught Cathecism.Indeed, according to this tradition, on the 10th February 1823, some children were taken to attend mass at Floriana and were then accompanied to the Convent of the Minori Osservanti in Valletta (today known as the Convent of the Franciscans of St Mary of Jesus or Ta’ Ġieżu) where they were given bread without any difficulty or trouble. The same ritual was intended to take place the day after. Yet no one had any idea that a series of errors would eventually lead to such a great tragedy.

Everything started according to plan on 11th February 1823. The children were gathered in a group and were taken to mass at Floriana. However, when the ceremony lasted an hour longer than usual, the children’s procession to the Convent in Valletta coincided with the end of the Carnival celebrations, when a great number of jubilant people were returning home. This led to the next blunder, as a number of adults and children who were passing by and who knew of this tradition, secretely mixed in with the other boys in order to share the bread which would be distributed.

Everything started according to plan on 11th February 1823. The children were gathered in a group and were taken to mass at Floriana. However, when the ceremony lasted an hour longer than usual, the children’s procession to the Convent in Valletta coincided with the end of the Carnival celebrations, when a great number of jubilant people were returning home. This led to the next blunder, as a number of adults and children who were passing by and who knew of this tradition, secretely mixed in with the other boys in order to share the bread which would be distributed.In line with the usual arrangement, these boys were to enter into a corridor of the Convent from the door of the vestry of the Church, and were to be let out through the opposite door of the Convent in St Ursula Street, where the bread was to be distributed. In order to prevent the boys who received their share from reentering to take a second helping of bread, it became customary to lock the door of the vestry. Yet this time, since the children were late, this door was left open for a longer time so that they could enter. As the sun was setting and darkness crept in, nobody realized that other men and boys who did not form part of the original group were entering too.

Soon, the boys who were queuing in the corridor found themselves being pushed by these trespassers as they forced themselves in. The situation worsened when eventually the vestry door was closed as usual and the children were shoved further at the end of the corridor where a door stood half open so that no one could get back in a second time.

That day was certainly ill-fated when further mistakes continued to occur. In fact, a lamp which was usually lit in the corridor was somehow put out, leaving the overcrowded area in total darkness. This confused the people even more and as they tried to push themselves forward in order to get out, the boys who were at the front fell down a flight of eight steps on top of each other, thereby blocking further the door which happenned to open inwards.

Suddenly, both those who were distributing the bread and the Convent’s neighbours began to hear children shrieking out. They ran to give their assistance but a lot of time was wasted as they tried to open the two doors which led to the corridor in order to reach the people inside.

Eventually, many children were taken out fainting but recovered soon. Others appeared lifeless but were brought to their senses some time afterwards. Regretfully, 110 boys from 8 to 15 years of age perished from suffocation when they were pressed together in such a small place or because they were trampled upon.

After investigating this accident, the Lieutenant Governor concluded that this was an unfortunate accident caused by the succession of errors mentioned above. Consequently, no one was accused for the death of these children since these acts were not done on purpose to harm them. In fact, Plasket commented that everyone had collaborated to assist these poor boys and even the victims’ relatives had allowed the police and the soldiers to work speedily and diligently in order to save as many children as possible. He insisted that were it not for this, the tragedy could have been much worse.

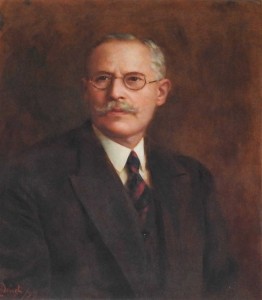

After investigating this accident, the Lieutenant Governor concluded that this was an unfortunate accident caused by the succession of errors mentioned above. Consequently, no one was accused for the death of these children since these acts were not done on purpose to harm them. In fact, Plasket commented that everyone had collaborated to assist these poor boys and even the victims’ relatives had allowed the police and the soldiers to work speedily and diligently in order to save as many children as possible. He insisted that were it not for this, the tragedy could have been much worse.As I followed further this narrative by focusing on the names mentioned in Plasket’s report, I succeeded to trace the Captain of the Malta Fencibles who led the soldiers during this tragic moment. It was his descendant, Marquis Nicholas De Piro who led me to see Colonel Marquis Giuseppe De Piro’s portrait which is located at Casa Rocca Piccola in Valletta.

An interesting discussion ensued between us during which the present Marquis informed me also about General Sir George Whitmore who headed the Royal Engineers’ detachment on Malta as its Colonel Commandant between 1811 and 1829. Whitmore had written about his experiences in Malta and had also produced some illustrations related to our islands. Interestingly, Marquis Nicholas De Piro was in possession of a copy of one of these ancient illustrations in the form of a very small slide, which showed some individuals being trampled upon by a group of other people. He wondered whether this slide could be portraying this misfortunate accident of the Carnival of 1823. Yet no children are included in this representation and so it is not clear whether it actually depicts this narrative.

An interesting discussion ensued between us during which the present Marquis informed me also about General Sir George Whitmore who headed the Royal Engineers’ detachment on Malta as its Colonel Commandant between 1811 and 1829. Whitmore had written about his experiences in Malta and had also produced some illustrations related to our islands. Interestingly, Marquis Nicholas De Piro was in possession of a copy of one of these ancient illustrations in the form of a very small slide, which showed some individuals being trampled upon by a group of other people. He wondered whether this slide could be portraying this misfortunate accident of the Carnival of 1823. Yet no children are included in this representation and so it is not clear whether it actually depicts this narrative.My research ended at Ta’ Ġieżu Church and I watched in silence the area where these children lost their lives. Sadness engulfed me when I climbed up the steps on my way back while pondering how these children could end in this way for a piece of bread.

(This article was published in the Carnival Supplement issued with the Times of Malta dated 3rd February 2016)

Travelogue

Archives

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jan | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

Recent Posts

- A MATTER OF FATE

- MALTA’S PREHISTORIC TREASURES

- THE MAGIC IS IN THE DETAIL

- THE SELLING GAME

- NEVER FORGOTTEN

- Ġrajjiet mhux mitmuma – 35 sena mit-Traġedja tal-Patrol Boat C23

- AN UNEXPECTED VISIT

- THE SISTERS OF THE CRIB

Comments

- Pauline Harkins on Novella – Li kieku stajt!

- admin on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Albert on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Martin Ratcliffe on Love in the time of war

- admin on 24 SENA ILU: IT-TRAĠEDJA TAL-PATROL BOAT C23