Posts Tagged ‘Vittoriosa’

-

THE MAGIC IS IN THE DETAIL

Although the main characters of the nativity scene are Joseph, Mary and baby Jesus, different cultures have added and altered the original representation in order to include their own characteristics. Some of these varying interpretations can be viewed in a permanent exhibition at the Inquisitor’s Palace in Birgu, which also houses the National Museum of Ethnography.

Although the main characters of the nativity scene are Joseph, Mary and baby Jesus, different cultures have added and altered the original representation in order to include their own characteristics. Some of these varying interpretations can be viewed in a permanent exhibition at the Inquisitor’s Palace in Birgu, which also houses the National Museum of Ethnography.In Malta, it was St George Preca (1880 – 1962) who fostered a lasting Christmas cult through his Society of Christian Doctrine. On Christmas Eve of 1921, he organized the first procession with a statue of baby Jesus. He also started the tradition of giving a crib and a statue of baby Jesus to every child who attended the MUSEUM centres.

In the exhibition, an image of Preca looks over at a rudimentary crib which has initiated a tradition that is still celebrated nowadays. A detailed diorama portrays further this tradition, showing a MUSEUM Superior handing out a crib to a boy, while a number of other children are already joyfully holding their cribs. An altar which is included in the diorama is decorated with flowing white vetch.

Another diorama looks like a time capsule showing the traditional procession of baby Jesus together with other local customs. Not only can one observe the MUSEUM members carrying the statue of baby Jesus, but one can also delight at the children carrying lights and Christmas messages while singing Christmas carols. The context is further enriched by the presence of traditional Maltese town houses, with their colourful wooden doors and with their wide open windows decorated with a small statue of baby Jesus.

Another diorama looks like a time capsule showing the traditional procession of baby Jesus together with other local customs. Not only can one observe the MUSEUM members carrying the statue of baby Jesus, but one can also delight at the children carrying lights and Christmas messages while singing Christmas carols. The context is further enriched by the presence of traditional Maltese town houses, with their colourful wooden doors and with their wide open windows decorated with a small statue of baby Jesus. These two dioramas form part of a set that was donated to Heritage Malta by Austin Galea; a well-established artisan and personality among local crib enthusiasts, and a founding member of the Għaqda Ħbieb tal-Presepju (Malta). The set of dioramas give life to further Christmas traditions, such as the sermon of the altar boy during Christmas’ eve mass, a large crib displayed for public viewing, a group of craftsmen in a workshop manufacturing statues and cribs, and a Christmas lunch being enjoyed by a family.

These two dioramas form part of a set that was donated to Heritage Malta by Austin Galea; a well-established artisan and personality among local crib enthusiasts, and a founding member of the Għaqda Ħbieb tal-Presepju (Malta). The set of dioramas give life to further Christmas traditions, such as the sermon of the altar boy during Christmas’ eve mass, a large crib displayed for public viewing, a group of craftsmen in a workshop manufacturing statues and cribs, and a Christmas lunch being enjoyed by a family. Galea has also donated two large nativity scenes which are typically exhibited in windows of private houses during the Christmas season in Malta. Other donations by him include different traditional statues of baby Jesus. Traditionally, the baby Jesus statues were made of wax to obtain a soft and translucent finish. The statues were eventually dressed up in an embroidered tunic, while many borrowed real hair from a toddler’s crowning curls.

Galea has also donated two large nativity scenes which are typically exhibited in windows of private houses during the Christmas season in Malta. Other donations by him include different traditional statues of baby Jesus. Traditionally, the baby Jesus statues were made of wax to obtain a soft and translucent finish. The statues were eventually dressed up in an embroidered tunic, while many borrowed real hair from a toddler’s crowning curls. A large Maltese crib is also part of Galea’s generous donation. The crib is a comprehensive study of Maltese traditions in itself. Typical Maltese figurines are dressed in traditional local costumes, and among them, one also finds the unique Maltese symbolic characters. The Stupefied figurine represents those who are impressed by the profound meaning of the unique happening. The Beggar represents the poor who find consolation in Christ. The Climber represents those who find it difficult to understand the significance of Christ’s incarnation but strive to discover out. The Folk Singers represent communal association in praising the Lord, while the Sleeper represents those who ignore the immeasurable benevolence of Christ. The rugged landscape with its terraced fields, sparse vegetation, low-profile unpretentious farmhouses and a windmill are reminiscent of the rural ambience of the old times.

A large Maltese crib is also part of Galea’s generous donation. The crib is a comprehensive study of Maltese traditions in itself. Typical Maltese figurines are dressed in traditional local costumes, and among them, one also finds the unique Maltese symbolic characters. The Stupefied figurine represents those who are impressed by the profound meaning of the unique happening. The Beggar represents the poor who find consolation in Christ. The Climber represents those who find it difficult to understand the significance of Christ’s incarnation but strive to discover out. The Folk Singers represent communal association in praising the Lord, while the Sleeper represents those who ignore the immeasurable benevolence of Christ. The rugged landscape with its terraced fields, sparse vegetation, low-profile unpretentious farmhouses and a windmill are reminiscent of the rural ambience of the old times.Besides donating his first clay crib figurines which were given to him by his aunties and an unusual crib made of sacks that was constructed by him, Galea shares also his knowledge relating to Christmas crib construction in a short video which forms part of this exhibition.

Another intriguing element in this exhibition is the donation of numerous miniature cribs which were brought by Albert and Lina McCarthy from all over the world. The professional tour managers have been gathering this impressive collection since the early 90s. Their collection amounts to more than 500 miniature works of art, a representative selection of which is on display at the Inquisitor’s Palace.

Another intriguing element in this exhibition is the donation of numerous miniature cribs which were brought by Albert and Lina McCarthy from all over the world. The professional tour managers have been gathering this impressive collection since the early 90s. Their collection amounts to more than 500 miniature works of art, a representative selection of which is on display at the Inquisitor’s Palace.Exhibited in four different sections, the varying nativity scenes representing North and East Europe, Southern Europe and the Near East, North and South America, and Africa, Asia, the Far East and Australia are simply enchanting. The magic is in the detail of each crib which presents the nativity scene in various contexts, with distinct characters and in diverse materials.

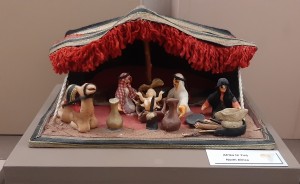

Some of the most notable are the terracotta nativity sets from Hungary and Peru, the ceramic sets from Denmark and the Philippines, the engraved wooden shoe from Amsterdam, the wooden sets of Germany, Austria, Japan and Iran, the metallic artwork from Bali, the sack nativity set from Sri Lanka and the clay figurines of North Africa set in a bedouin tent, dressed in traditional costumes and accompanied by a camel instead of farm animals.

Some of the most notable are the terracotta nativity sets from Hungary and Peru, the ceramic sets from Denmark and the Philippines, the engraved wooden shoe from Amsterdam, the wooden sets of Germany, Austria, Japan and Iran, the metallic artwork from Bali, the sack nativity set from Sri Lanka and the clay figurines of North Africa set in a bedouin tent, dressed in traditional costumes and accompanied by a camel instead of farm animals.A visit to this permanent exhibition held at the Inquisitor’s Palace is most educational and entertaining for children, and also curious and insightful for adults. The exhibits are a tribute to local and foreign artisans who have used their creativity to reproduce the significant nativity scenes in various intriguing representations.

(Published in Christmas Times magazine issue with The Times of Malta dated 7th December 2019)

-

Fixing Time

I met Stephen Zammit on the roof of the Malta Maritime Museum in order to watch closely the mechanism of the British 19th century clock which he has restored last year. This was certainly an exclusive moment since I was clearly warned that Zammit is very possessive of ‘his’ clocks.

In fact, there was a magnificent view of the Vittoriosa Marina but Zammit’s eyes and admiration were dedicated only to the imposing clock tower which was sheltering the elaborate clock’s mechanism within its walls.

“Originally this clock was located within a small steeple which overlooked dock number one,” he informed me. “After it was moved here, the dials of this clock face Cospicua, Senglea and Valletta. Apart from its mechanism, Heritage Malta restored also the dials of this clock according to how it looked originally in old pictures and paintings; that is with a black face and with gold numbers and dials. Isn’t it a beauty now?”

Zammit has always been fascinated by clocks. His first interest was sparked off by Ħ’Attard’s parish’s tower clock where he attended church as a small boy.

At only 11 years of age, he started to open the wind-up alarm clocks which they had at home in order to observe their components. Soon, he ventured to repair some of these clocks by noting what was out of place or what was broken.

“When I found a missing or a broken part, I used to go and order it from a clock spare-parts’ agent in Valletta,” he reminisced. “From him, I learnt and memorized the names of each item until eventually I got to know each section of a clock.”

Later on, he turned to watches which were much smaller and required more attention. It was his utter joy to hear an old watch ticking again after he sorted out its malfunctioning part.

He became involved in church clocks incidentally, when Rev. Can. Louis Suban, who was the parish priest of Msida, asked Zammit’s uncle whether he knew someone who could repair the 18th century parish clock.

“My uncle recommended me and Fr Suban contacted me. I was delighted to work on such an antique clock! When I went to see it, I noticed that the clock had severely deteriorated parts, both due to the natural elements and also because of wear and tear. After these were replaced, the clock came back to life and it is still working,” he said proudly.

“Fr. Suban has a keen interest in clocks since his ancestors used to produce clocks for churches including those of the parishes of Marsaxlokk and Ħal-Safi. Incidentally, they also made some repairs on this clock here,” Zammit said as he pulled out a key and let me in to see the mechanism’s structure.

He pointed at a section among the intricate metal configuration where there was the engraved signature – Brothers Suban. Malta. 1896.

“Generally, all clock makers and repairers leave an identifying mark in order to record their work,” he told me as he indicated another signature. “This inscription reveals who constructed this system, where and when – Matthew Dutton. London. 1810.”

By detecting these clues on several clocks, Zammit became aware of the various clock makers and repairers that we had in Malta along the centuries.

“I feel very disappointed when I hear people talking only about particular clock makers and ignore all the rest as if they never existed,” he proclaimed.

“For example, many know about Michelangelo Sapiano because he was one of the most prolific workers in the sector of clock making. Indeed, he was lucky enough to live in a time when there was a great demand for church clocks and he made the best of this opportunity.”

In fact, Sapiano was behind the construction of around 21 clocks of various parishes, including that of the parish of Ħal-Luqa.

“When I was called to repair Sapiano’s clock in Ħal-Luqa, I could clearly understand the genius of this man. I was enthralled to follow his thinking through his work and to notice how he maneuvered a system so that the mechanism’s structure regulated three different time dials and another one which showed the date.”

According to Zammit, Sapiano learnt this trade from the Tanti family who manufactured about seven local parish clocks, including those of Qrendi and Ħal-Tarxien. Yet somehow, clock enthusiasts who admire and talk much about Sapiano, seem to know nothing about his predecessors.

For more than thirty years, Zammit had the opportunity to work on several huge parish clocks and by time, he acquired an instinctive ability of how to recognize the various clock makers. Likewise, he became inherently skilled in repairing the different systems by getting acquainted to the standard form of the core of these structures and also to the evolving variables of each constructor.

Zammit used the clock in front of us in order to help me to understand how it functioned.

“As you can see, there are three sections,” he said. “The one in the middle is connected to a pendulum so that it could regulate the time. The other sections are the ones which moderate the quarters and the hours.”

All along our discussion, we were accompanied by the regular ticking of the clock. Yet, suddenly, a sudden twitch on one of the gear wheels seemed to awaken the whole mechanism as many more items of the metallic structure moved, rotated and flapped, whilst a lever pulled and pushed high up to the iron hammers and instilled them to bang on the bells in order to mark the time.

We both stood in reverent silence as the bells chimed gracefully and their melodious echo slipped in the small room.

“You would probably think that by now I have got used to this experience,” Zammit broke the silence, once the bells stopped ringing and the apparatus calmed down to its regular ticking. “However, as you can see, I am still completely bewitched by the spell of these compositions.”

Being also a violinist with the Malta Philharmonic Orchestra, he is naturally enraptured by the involvement of the musical tones which are operated by this system.

“I come to regulate this clock once a week,” Zammit informed me as he started to manipulate the three weights of the clock.

I stood back and observed as he made the necessary adjustments. From the mechanism’s obliging response, I seemed to sense an aura of a corresponding comradeship.

“Each time that I go to do some work on a clock, I just can’t resist the temptation to stay for another whole hour in order to confirm that everything is working well. There were even moments when people forgot that I was in the clock tower and locked me in the church,” he admitted as he chuckled warmly.

There was again an abrupt movement within the clock’s structure. Another quarter of an hour had passed and the system activated itself again. This time, I was not taken by surprise. Like Zammit, I was simply spellbound.

(This article was published in the Business of Time supplement that was issued with The Times of Malta dated 30th October 2014)

Travelogue

Archives

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jan | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

Recent Posts

- A MATTER OF FATE

- MALTA’S PREHISTORIC TREASURES

- THE MAGIC IS IN THE DETAIL

- THE SELLING GAME

- NEVER FORGOTTEN

- Ġrajjiet mhux mitmuma – 35 sena mit-Traġedja tal-Patrol Boat C23

- AN UNEXPECTED VISIT

- THE SISTERS OF THE CRIB

Comments

- Pauline Harkins on Novella – Li kieku stajt!

- admin on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Albert on IL-KARNIVAL TRAĠIKU TAL-1823

- Martin Ratcliffe on Love in the time of war

- admin on 24 SENA ILU: IT-TRAĠEDJA TAL-PATROL BOAT C23